The entrepreneurship journey varies for every entrepreneur, but there are often a few similarities. For the vast majority, it is a long-standing interest in a field and a resilient attitude in the face of setbacks.

While Obasegun Ayodele, Co-founder and CTO of Vilsquare, has taken various routes to where he is today, his interest in building hardware solutions has been constant throughout his journey

His introduction to the hardware space came while he was in secondary school at LAUTECH International College in Ogbomosho, a town in the South-Western part of Nigeria.

Studying at a school that enjoyed a relationship with the Electrical and Electronics Engineering department of the Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH) meant that he was exposed to the practical aspects of the discipline.

And in 2010, he was admitted to study Electronics and Electrical Engineering at the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU).

OAU is one of Nigeria’s oldest universities, having been established in 1962 shortly after the country's independence. It has produced several successful entrepreneurs in Nigeria’s startup space, some of whom started as students.

As data from Techpoint Africa’s West Africa Startup Decade Report reveals, OAU produced the highest number of founders who raised $1m cumulatively in the last decade. Thus, Ayodele had no shortage of examples to follow as a student.

Testing the waters of entrepreneurship

As a student, he got involved in many communities where he honed his technical and leadership skills. He also built and failed at a few startups in the hardware space.

His first startup, Alcacia Systems, was a hardware consulting firm that helped companies build hardware solutions such as billboards and screen displays. After that failed, he started Pragmatic Embedded, a machine-to-machine solution for home automation.

Join over 3,000 founders and investors

Give it a try, you can unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

His next venture was PubCulture – a platform similar to, but a few years ahead of Canva. On the platform, users could choose a template to create a design before downloading it. That, too, failed.

Three failures would discourage even the most resilient of people, but Ayodele was not done. His next startup, AirMoney, tried to solve the challenge of trust in online payments.

With most Nigerians sceptical about using their cards online, AirMoney allowed users to convert airtime to cash which they could then use to make payments online.

Like the others, AirMoney did not take off, and he soon switched his focus to Humane, a device that made smartphones accessible to the blind. It won the Microsoft Imagine Cup in 2016.

Without sufficient support, the team dropped the idea of Humane and moved on to other things. He moved to Lagos after his studies and joined iQube, a tech company building solutions for businesses.

Building Vilsquare

While building these startups, he realised that his lack of business skills was a major reason they failed, so in 2017, he joined iQube as a business developer.

“At iQube, I was not doing anything hardware. I was in sales and marketing because one of the biggest lessons from Humane was that we knew nothing about sales, marketing, or business development. They're not taught in any engineering school, even though there are entrepreneurship courses. Everybody is just focused on building without thinking of how to sell these skills.”

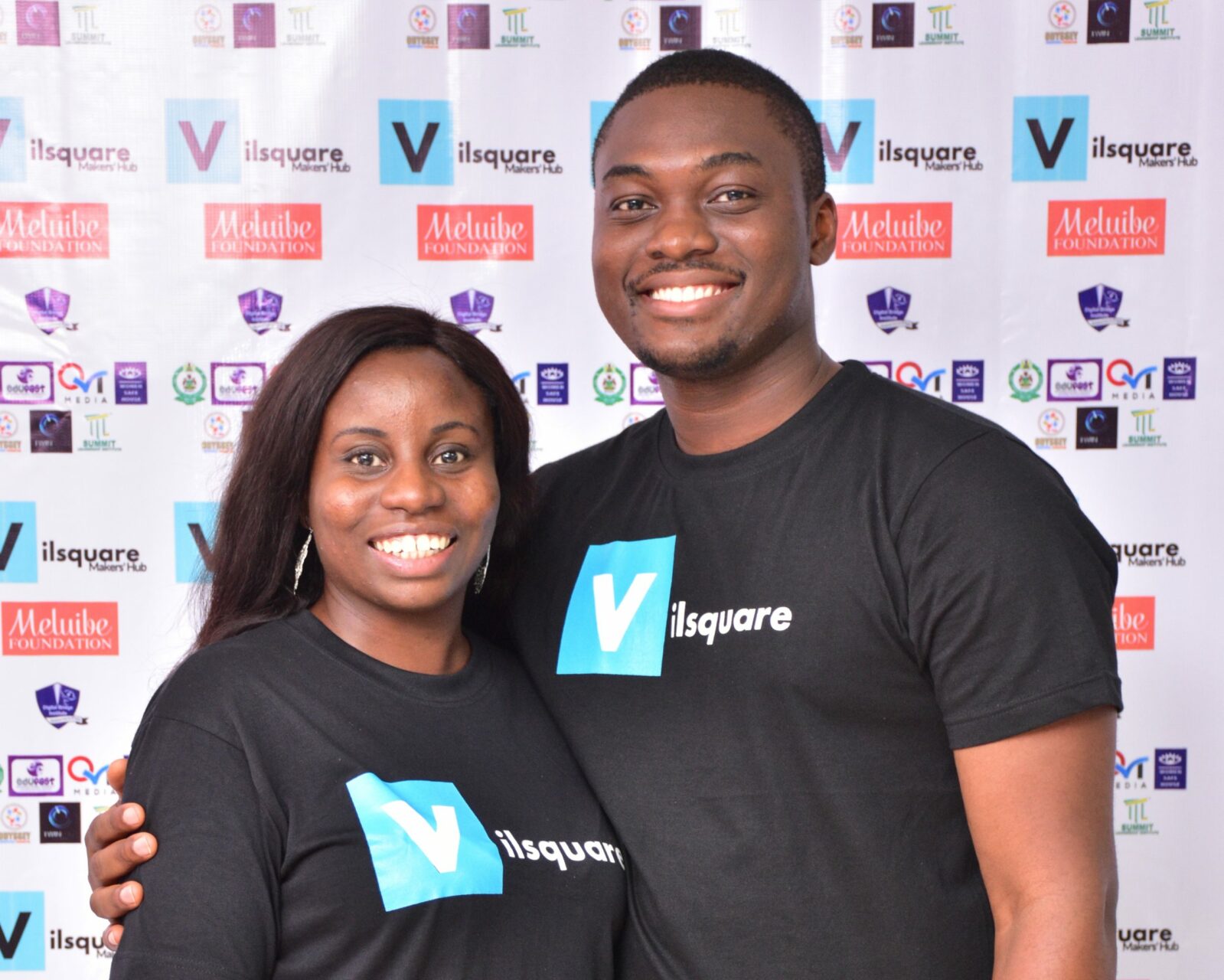

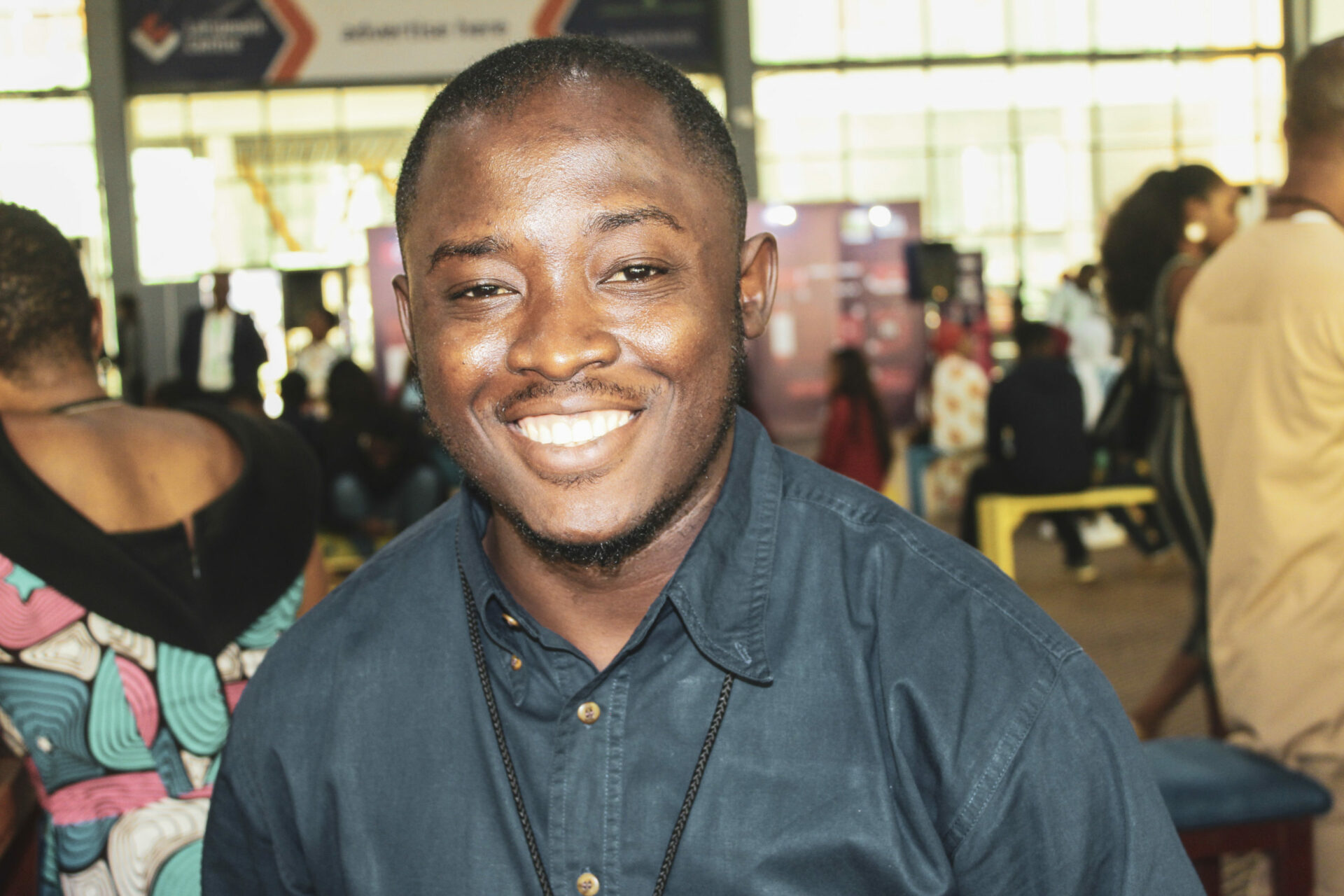

He was there until 2018, when Vilsquare launched. While at iQube, he had led a project with another company where his Co-founder and CEO, Obialunanma Nnaobi, worked.

When he had the idea for Vilsquare, he flew to Abuja to discuss it with her. At first, she was reluctant about leaving her job to join Vilsquare full-time, but Ayodele was sure that the business needed someone with her expertise.

“She had come from banking to public policy and governance, and I felt it was necessary to bring someone with her skillset. I had the technical skills and some experience with sales and business development, but none in policy or corporate governance, and I believed these were important skills to have.”

She ultimately joined a year later — a move that Ayodele credits with turbocharging their efforts.

To get started, he dipped into his savings to register the company and get a few other things set up. With little financial support, they started as an IT consulting company providing various services, including digital marketing. The money they made from these consulting gigs kept the lights on.

In 2018, Vilsquare launched a national hackathon that brought people from all parts of the country together to solve problems using hardware solutions. The hackathon helped the company build a community that it would later leverage.

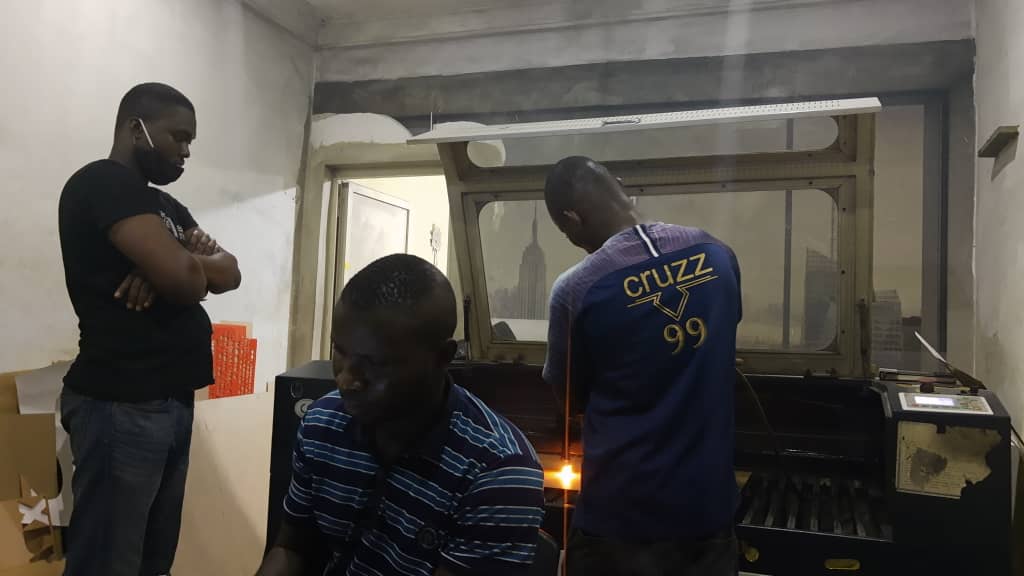

Towards the end of 2019, the startup pivoted and became a research and development centre that helped businesses go digital. Along the way, Vilsquare developed a few solutions internally.

The new normal

2020 brought the coronavirus pandemic, and one day they woke up to messages terminating their retainerships. With a major revenue source closed, they were in a race against time to develop solutions that took advantage of the challenges of the time.

That solution was the VoltMicroscope – a handheld digital microscope over ten times cheaper than existing alternatives. For context, a microscope produced outside Nigeria could cost anything from ₦250,000 ($608) to as much as ₦1,000,000 ($2,432). As a result, most secondary schools and even universities do not have enough microscopes for students to practice with.

At an exposition in March 2020 hosted by Nigeria’s Ministry of Science and Technology, they sold 20 pieces of the VoltMicroscope, gathering valuable feedback with which they improved the product.

Two months later, they launched version 34E. The previous version was made of wood and cost ₦15,000 ($36), but the version 34E was made from plastic and cost ₦25,000 ($60).

Encouraged by the response from the previous version, they began targeting schools, research institutions, and even government institutions.

Those efforts paid off, and Ayodele revealed that the startup has now sold 40,000 pieces of the VoltMicroscope, and it is being used in 27 universities in Nigeria, including Nile University, Baze University, University of Abuja, the Prototype Development Agency in Enugu, Afe Babalola University, Obafemi Awolowo University, University of Lagos, and Yaba College of Technology.

The startup also has military clients, including the Nigerian Defence Academy and the Airforce Institute.

Its factory reportedly manufactures 1,000 microscopes a week and has shipped products to the United Kingdom, Kenya, and South Africa. While this was happening, they received word from Just One Giant Lab (JOGL) informing them of an available fund for COVID intervention. Using the funds, they built the Volt School to go with the VoltMicroscope.

The Volt School is an edtech platform that uses the WAEC curriculum to create audio-visual content for students in secondary school. With the help of subject matter experts in their community, the startup created audio-visual lessons for the platform.

“The platform was launched towards the end of June 2020, and by September 2020, there were over 1,000 students from Ghana, Sierra Leone, Liberia, The Gambia, and Nigeria.”

Volt School has a free version with six subjects and a premium version that costs $20 with three extra subjects — Mathematics, Economics, and English. The platform now boasts 13,000 students in 11 African countries. Through a partnership with OAU, they integrated an online platform that enabled students to run simple experiments in a gamified environment.

Navigating the hardware ecosystem

In the three years since launching Vilsquare, Ayodele and his co-founder have faced several challenges. A major one being access to funding — an issue that is more prevalent among hardware startups that typically need more money than software startups.

He discloses that choosing to run a consultancy helped with cash flow.

“The retainership model saved us because it meant we had cash flow. One of the things we soon discovered about running a business was that cash flow was more important than profit and even revenue.”

While VC investment in Africa is on the rise, Vilsquare has not received any venture funding.

“We didn’t find investors who were willing to bet on us. We reached out to many people to fund Vilsquare, and a lot of them told us it was not within their investment thesis. At some point, we just decided to build the business based on our sales.”

Bureaucracy in government is another problem the startup has faced.

“I don’t think there’s been any government official that saw what we do and did not believe in us. The National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure is one such agency.

“The problem has always been with the bureaucracy. Since we are not venture-backed, we cannot afford to wait too long for the bureaucracy,” he declares.

Getting buy-in locally has also been a challenge.

“We consume a lot of foreign things. We prefer to save our money to buy an iPhone than buy a phone made in Nigeria for a fraction of that cost. People prefer to import cars than buy a car made in Nigeria, so most of the time when we create products, and we go to the end-users, they reject us.”

While he wants more local patronage, he is insistent that it must be dependent on the quality of their product and not simply out of a desire to support local businesses.

“I want you to buy one because you need it,” he says.

Like most entrepreneurs, Ayodele laments the difficulty of getting the right talents at a reasonable price.

“Most talents want instant cashouts. Annoyingly, even the ones who don’t have skills are also demanding big paychecks.

“They feel having had a hard time in school automatically qualifies them for a big paycheck, and this is why unemployment is rising. How do you grow your business if you cannot hire talents at the right price?”

Having made significant progress since launching in 2018, he reveals that the startup plans to consolidate on the successes it has recorded.

“We’re focused on manufacturing consumer electronics in the education space. We may enter another industry this year or next.

“We would also be building a bigger factory and equipping them with more tools, automating a lot of our products and hiring more engineers. So far, we’ve run away from the software arm of powering our hardware products, but we’ll be looking into that.”

With a mission to provide Africans with low-cost hardware solutions, Ayodele is confident that the startup can only get bigger. For now, the focus is on consolidating the progress it has made since launching.