Water. Earth. Fire. Air.

If you are an Avatar: The Last Airbender head like me, you are probably expecting to see the following tagline, "Long ago, the four nations..."

All in due time, my friend. But please, follow closely.

On Monday, August 29, 2005, the historic storm, Hurricane Katrina, hit cities lined up on the Louisiana-Mississippi border in New Orleans. For many, that was the last time they saw their homes and over 1,000 lives were lost.

On Boxing Day in 2004, the world's third-largest earthquake occurred, resulting in one of the worst natural disasters — The Asian Tsunami. An estimated 227,898 people died in 14 countries on the coastline, including India, Indonesia, and Thailand.

So, why the Avatar reference and what does it mean here? The original idea was to list different natural disasters, but I felt that all four elements play a vital role in these situations. Water: tsunamis and earthquakes; Earth: the world; Air: tornadoes and earthquakes; and Fire: the aftermath.

But I digress.

A common ground connecting both disasters is the major focus of this article. But before that, why mention the disasters in the first place? What is the connection?

In both situations, the NigeriaSat-1, built by the UK’s Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL) in 2003, was the first satellite to send images of the US east coast after Hurricane Katrina. It also provided valuable images for aid workers following the Asian Tsunami.

Be the smartest in the room

Give it a try, you can unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Before being decommissioned in 2014 as part of the Disaster Monitoring Constellation, NigeriaSat-1 was used to respond to floods in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and West Africa. It has also been used for various mapping campaigns like the Amazon and Vietnam’s coastal areas.

Nigeria does have other satellites, and they’ve been used in different situations, but before that, let’s do some backtracking.

Table of Contents

- A history of Nigeria’s space programme

- What Nigeria’s National Space Policy looks like

- Down the rabbit hole of implementation

- Notable achievements by NASRDA

- Going back to the basics

- What is the solution?

- A new age?

A history of Nigeria’s space programme

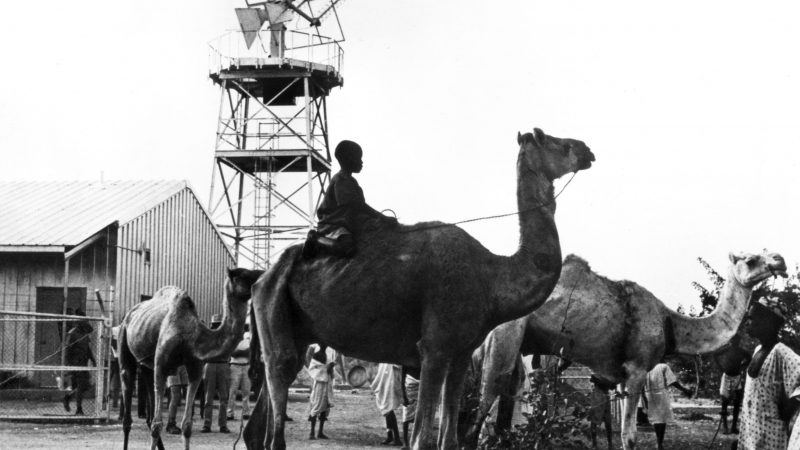

Nigeria's space history is a long and chequered one. Few people know — or remember — that the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) built the first satellite earth station in Nigeria, the NASA Tracking Station 5, in 1961 in Kano to monitor the Gemini and Apollo space missions.

Interestingly, the station was closed in 1963 before both missions were concluded in 1966 and 1972, respectively.

In 1976, at an ECOWAS meeting held in Addis Ababa, Nigeria first declared its space ambition, and it took 23 years to set up a space agency. In May 1999, the National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA) was born following the recommendation of a nine-person committee of experts constituted by the National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure (NASENI).

Side note: NASENI was established in 1992 by the Nigerian federal government on the recommendations of the White Paper Committee on the 1991 Report of a 150-member National Committee on Engineering Infrastructure comprising scientists, engineers, administrators, federal and state civil servants, economists, lawyers, bankers, and industrialists.

NASRDA's mandate is to “vigorously pursue the attainment of space capabilities as an essential tool for the socio-economic development and the enhancement of the quality of life of Nigerians.”

The agency is under the purview of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation.

Currently, Nigeria's space programme is managed by NASRDA. And in 2000, the National Space Policy (NSP) was approved, and a 25-year roadmap for its implementation was endorsed in 2005. But we’ll get to those in a bit.

In 2006, the state-owned Nigerian Communications Satellite (NIGCOMSAT) Limited was formed to manage and operate Nigeria’s communication satellites under the Ministry of Communication and Digital Economy.

In its 15 years of existence, the company, a limited liability enterprise that is yet to turn a profit, does not have an establishing Act and has been the subject of controversy after recently claiming it would acquire two new satellites in 2023 and 2025.

It also has a subsidiary, GeoApps Plus Limited, which is expected to handle the sale of satellite images acquired by Nigeria’s earth observation satellites. According to its Facebook page, it provides training in Geographic Information System and Remote Sensing for Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs), and the military, among others.

In 2017, after the Defence Space Administration Act was passed into law, and following the suggestions of the NSP, the Defence Space Administration (DSA) was officially commissioned to acquire more space science technologies to aid the military.

Formerly known as the Defence Space Agency, the DSA was first established on October 9, 2014, and is currently training several engineers in partnership with NIGCOMSAT and NASRDA.

But there’s still a lot to unpack from the NSP and we’ll be taking a look soon.

What Nigeria’s National Space Policy looks like

As we found out in 2018, as with most countries, Nigeria’s space programme is shrouded in secrecy.

By some stroke of luck and a dedicated LinkedIn search, I found the profile of Dr Halilu Ahmad Shaba, NASRDA DG, who agreed to talk to me for this article.

I asked him what kind of policies we might expect under his tenure, and while he didn’t tell me, he said one thing for certain, the NSP will be reviewed. A task that would be done alongside the overhaul of the current roadmap, which President Muhammadu Buhari has sanctioned.

But while we await the review, we can visit the current policy.

The NSP is a ten-chapter document outlining several objectives like defence and law enforcement, disaster prediction, earth observation, poverty alleviation, promotion of international cooperation, and the establishment of research centres.

It also provides Nigeria’s space economic model, a public-private partnership that involves short, medium, and long-term plans.

- Short-term, the government is responsible for all investments in space technology development.

- Medium-term, the government implements the partial commercialisation of NASRDA’s products and services developed during the short-term economic development plan.

- Long-term, the government partners with the private sector to implement the public-private partnership framework for the space programme.

To achieve this, the roadmap contains benchmarks:

- Launch of NigeriaSat-1 by 2002

- Training of Nigerian engineers to build earth observation (EO) satellites abroad by 2006

- Launch of two new satellites by 2011

- Training of Nigerian astronauts by 2015

- Synthetic Aperture Radar by 2015

- Development and Building of Made in Nigeria Satellites by 2018

- Development of Rocketry/Propulsion Systems by 2025

- Development of Spin-Off of Allied Industries – Electronics, Software etc. by 2028

- Large-Scale Commercialisation of Space Technology & Know-how by 2030

Down the rabbit hole of implementation

As far as implementation goes, Nigeria has had some success. We already talked about NigeriaSat-1. NASRDA has also facilitated the training of engineers in building EO satellites, with the NigeriaSat-X solely built by Nigerians, alongside the Nigeria-Sat-2 launched by the SSTL in 2011.

The NigeriaSat-1 and NigeriaSat-X have a lifespan of seven years and should have deorbited in 2018. But, four years later, both are still functioning by “grace”, as said by Shaba, and as an expert I spoke to told me, Nigeria is getting more value for money.

In 2017, the EduSat-1, a collaboration between the Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA), Ondo State, Nigeria, and NASRDA, was built by Nigerians and launched from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, but was decommissioned in 2019.

As to astronauts, you’d probably remember the current Minister of Science, Technology, and Innovation, Ogbonnaya Onu, telling Nigerians in March 2016 that Nigeria would have an astronaut in space on or before 2030. Before then, a fraudulent email about a Nigerian astronaut stranded in space had circulated, eliciting varying reactions. However, Shaba confirms that this milestone has not been achieved.

Nigeria’s dream to launch in space by 2030 does not look any closer to reality. As of 2021, 44 satellites have been launched by 14 African countries, but none have been done from an African launch site.

As of 2019, the Centre for Space Transport and Propulsion (CSTP), Epe, Lagos State, has completed three successful experimental rocket launches.

But, due to the hushed nature of Nigeria’s space programme, we only know a previous milestone altitude of 10km before 2019. Although Shaba says it has increased since then.

“Because it can also be used for utility purposes, we made a case that we are not going to announce that. So we closed it to the public and only made some skeletal speeches about that.”

Communication satellites

One vital aspect of space technology is communication satellites. Although they may not provide as fast Internet speeds as subsea cables or be as reliable, in a country like Nigeria where broadband penetration is as low as 41%, any little thing helps.

Currently, however, satellites only contribute 0.2% to Nigeria’s Internet connectivity.

After the NigeriaSat-1’s successful launch, in 2004, the government contracted state-owned China Great Wall Industry Corporation Limited (CGWIC) to build the NigComSat-1, a communication satellite.

The NigComSat-1 was launched in 2007, but due to an anomaly in its solar array, which meant it did not have enough power, it was shut down in 2008. Thankfully, the Nigerian government had a failsafe insurance policy that enabled them to contract CGWIC again to build the NigComSat-1R.

The NigComat-1R was launched in 2011 and has a 15-year life span, and, just like its predecessor, was managed by NIGCOMSAT. It had the exact specifications as the NigComSat-1, seeing that it was a replacement.

In 2018, Reuters reported that Nigeria had agreed to a $550 million deal with the CGWIC once again for two communication satellites which were to be ready by 2020 and 2021. But there’s no accurate information as to whether the deal pushed through or not. Especially after the world’s focus moved to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Shaba, however, calls this move and the current one by NIGCOMSAT to contract new satellites as counterproductive to what has already been done by NASRDA in training engineers and building satellites.

“You cannot have two satellite manufacturing agencies. And NIGCOMSAT is [a] communications limited, and we said it should restrict itself to transpondence.”

Side note: Transpondence is the receiving, sending, or reciprocal actions of receiving and sending messages or information through transponders or one of various radio transmission devices.

Commercialisation of space tech

As Temidayo Onisosun, Founder, Space in Africa, an Africa-focused media, analytics, and consulting firm focusing on the space and satellite industry, explained, the space ecosystem is divided into upstream and downstream.

Like upstream companies in the oil and gas sector, space startups specialise in exploration and drilling. In the space ecosystem, this could mean rocket or satellite launching or space missions.

A company downstream would be more focused on remote sensing, communication, among others. Currently, Nigeria’s space ecosystem is mostly government run, especially in upstream activities.

To aid its 2030 goal of large scale commercialisation, in 2010, the NASRDA Act was passed, establishing the National Space Council (NSC) as regulator. The Act says the NSC can approve licences for space activities in Nigeria. It, however, makes no provision for private partnership, thus limiting private companies to a participatory role.

According to Shaba, as part of Nigeria’s medium-term goals, NASRDA’s products are to be commercialised.

“We try to call them and let them know. For example, if data is supposed to cost 30 million, we sell it at 25 million. You sell it and make your money. And then you return the remaining money to the agency.”

This data is information gotten from Nigeria’s available satellites.

Shaba also mentioned spin-offs from its Quick Win projects, which focused on specific issues like food security, human security, disaster management, climate change, data management, and educational packages in space science.

This included research done on the effect of high-frequency radiation on Wistar rats. A study which was to help the Agency determine the former on humans. Although it is not clear what this new research brings to the table as it appears to be a well-researched field. But, of course, science is always a curiosity.

In 2020, there were 23 Quick Win projects.

Notable achievements by NASRDA

For most Nigerians, in a country heavily hit by recession and facing continued insecurity, a space programme looks like vanity metrics, showboating, if you will. But space technology is quite important.

According to Statista, in 2020, the global space economy made approximately $446.9 billion, increasing from $428 billion in the previous year, with commercial space products and services accounting for almost 50% of the total turnover.

But beyond the economic impact, there are spillovers into other sectors, like agriculture, medicine, transport, the environment, and communications.

Over the last few years, NASRDA has worked with Nigerian and foreign military agencies to eliminate insurgency in West Africa.

According to The Guardian, the Agency used the NigeriaSat-X to produce a 10-metre digital elevation simulation map and vegetation density map of Sambisa Forest to help the military in the insurgency fight.

Basically, using data obtained from the satellite, NASRDA created a digital representation of the forest.

In 2012, NASRDA aided the Malian government during the civil war between Southern and Northern factions.

The media house also says, “the space agency donated over 4000 satellite images estimated to be worth ₦3 billion ($8.3 million) to Nigerian universities and research institutions, using NigeriaSat-1 alone. In all, NigeriaSat-1 directly contributed over ₦10.5 billion ($29 million) to Nigeria’s economy within its first nine years in orbit.”

These activities were also continued using the newer satellites, the NigeriaSat-2 and NigeriaSat-X.

In 2015, NIGCOMSAT won the contract to manage Belarus’ satellite, the BelinterSat-1, a revenue source which was estimated would bring in $400,000 annually.

Combining these with the Quick Win projects and several other spin-offs, it would appear the Agency has not completely failed.

However, although Shaba describes the Nigerian space ecosystem as “vibrant”, the country still lags behind, a problem he attributes to funding.

Going back to the basics

While I talked to Henry Ibitolu, a former Research Intern at NASRDA, he drew an interesting comparison with India.

“India right now has almost joined the league of countries launching rockets. When the US government, through NASA, sent rockets to Mars, they spent $2 billion. But when India leveraged its local manpower and technology to land a rover on Mars, they spent $20 million. That’s about 10% or less of what the US spent.”

I would later check the figures, and although not accurate, the numbers do say a lot. India spent $73 million and was successful on its first try.

To be fair, India’s space mission was done in 2013 while the US first successful Mars landing happened in 1975; several things made it much cheaper, even by previous standards.

India was careful to work with only local companies and engineers and made several adjustments to the technology to make it more efficient. A position made possible by an educational system that prioritises Science Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) courses.

Only two Nigerian Universities — Kwara State University, Malete, Kwara State, and recently the Lagos State University, Lagos, offer courses in aerospace and Aeronautical engineering.

I also found only one university — FUTA — that teaches remote Sensing and GIS as a course separate from geomatics and surveying. Several universities also offer Masters in Remote Sensing.

Ibitolu said the government should invest in STEM education.

“For example, the government should partner with universities to come up with innovative ideas. We have local technology that we can leverage on to make use of that.”

An opinion Oniosun shares.

Interestingly, all seven NASRDA research centres are situated in universities.

But beyond, education is funding. The space industry is capital intensive. I mean, we just talked about India spending $74 million for its Mars landing.

In 2021, NASRDA and its parastatals received ₦22.8 billion ($55.6 million) — 14.4% — from the total budget allocation for the Ministry of Science and Technology.

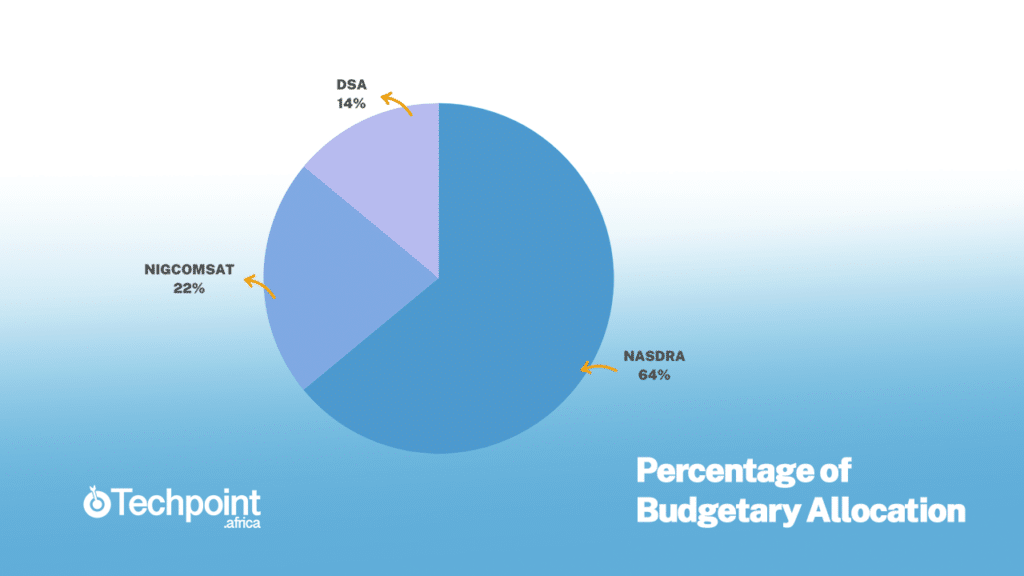

The total budgetary allocation for Nigeria’s space programme was ₦35.7 billion ($86.8 million), with NASRDA accounting for 64%, NIGCOMSAT, 22%, and DSA, 14%.

To put all of this into perspective, given the world’s current fascination with Mars and using NASA’s current Mars mission named Perseverance, which is expected to cost $2.7 billion, Nigeria’s entire space budget is barely 2% of the total cost.

A more obvious choice might be a satellite, which costs anything from $400,000 to $1 million to build.

It still leaves us with one conclusion, Nigeria’s space programme is grossly underfunded.

What is the solution?

While there is no clear-cut solution, Nigeria’s best bet lies in its space economic model, the long-term plan to be precise. A public-private partnership where the government works with privately-owned companies.

But Ibitolu advises NASRDA to achieve its dream of sending an astronaut into space before taking on a more regulatory role.

“Before you move to being a regulatory agency, you must have led by example. Before you tell people to do something, you must have done it yourself. But if you’ve not done anything and you are telling people to do it, it’s not possible. Because you don’t know.”

A position reminiscent of current startup woes in Nigeria.

Using the NASA-Space-X analogy, Oniosun believes NASRDA should work with universities and private companies empowering local startups.

“At some point, the US government, NASA had to trust SpaceX, to innovate and do awesome stuff. Maybe Nigeria has to do that.

“The Space agency has trained hundreds of persons to Masters and PHD level, but it doesn’t mean anything. It has not done anything before, and maybe they should stop wasting their money.

“Instead of the Agency trying to do all of that by itself, it should trust these companies and begin to outsource its technology.”

But what does the private sector look like in Nigeria?

Thriving or declining?

According to Ibitolu, the downstream sector is thriving with several remote sensing and GIS companies in the space. But currently, there’s no private company in the upstream space.

A problem that could also perhaps be attributed to the capital intensive nature of the industry, as funding remains a challenge. And Olayinka Fagbemiro, Assistant Chief Scientific Officer at NASRDA, believes banks could be the solution, most especially the African Development Bank (AfDB), but there has to be trust.

“In terms of the private sector, this is an aspect that the government has to work on. Why? There has to be an enabling environment. There has to be a certain ease of doing business in that aspect that would make individuals able to commit the huge, enormous resources that need to go into the private sector and be a player in the space programme.

“If banks, for example, can provide some sort of loans for startups in the space sector, there are a lot of smart, young Nigerians coming up daily with expertise, but the major challenge is capital. And Africa is losing out a whole lot as a result because Africa has a lot to gain from space products.”

But it would have to be a long term investment or credit plan. However, Shaba decries Nigerian investors’ eye for quick profit.

A new age?

In May 2021, Shaba was appointed as the new Director-General of NASRDA, and I asked him what to expect from NASRDA under his reign. Shaba’s answers: lots of restructuring, more satellites, and functioning in line with the government.

Ibitolu expects some changes.

“We are hopeful that we will see change with the new administration. When I did my IT with NASRDA, under the previous administration, I saw people being employed who had studied Yoruba. But we are hopeful we will see new developments at NASRDA.”

A position Fagbemiro agrees with.

Before writing this, I hoped to determine whether the Space Agency has failed in its duties. My conclusion is that, to a large extent, compared to other space programmes, while it cannot be regarded as a total failure, it cannot be regarded as an out and out success either.

But, it could be better. What say ye?