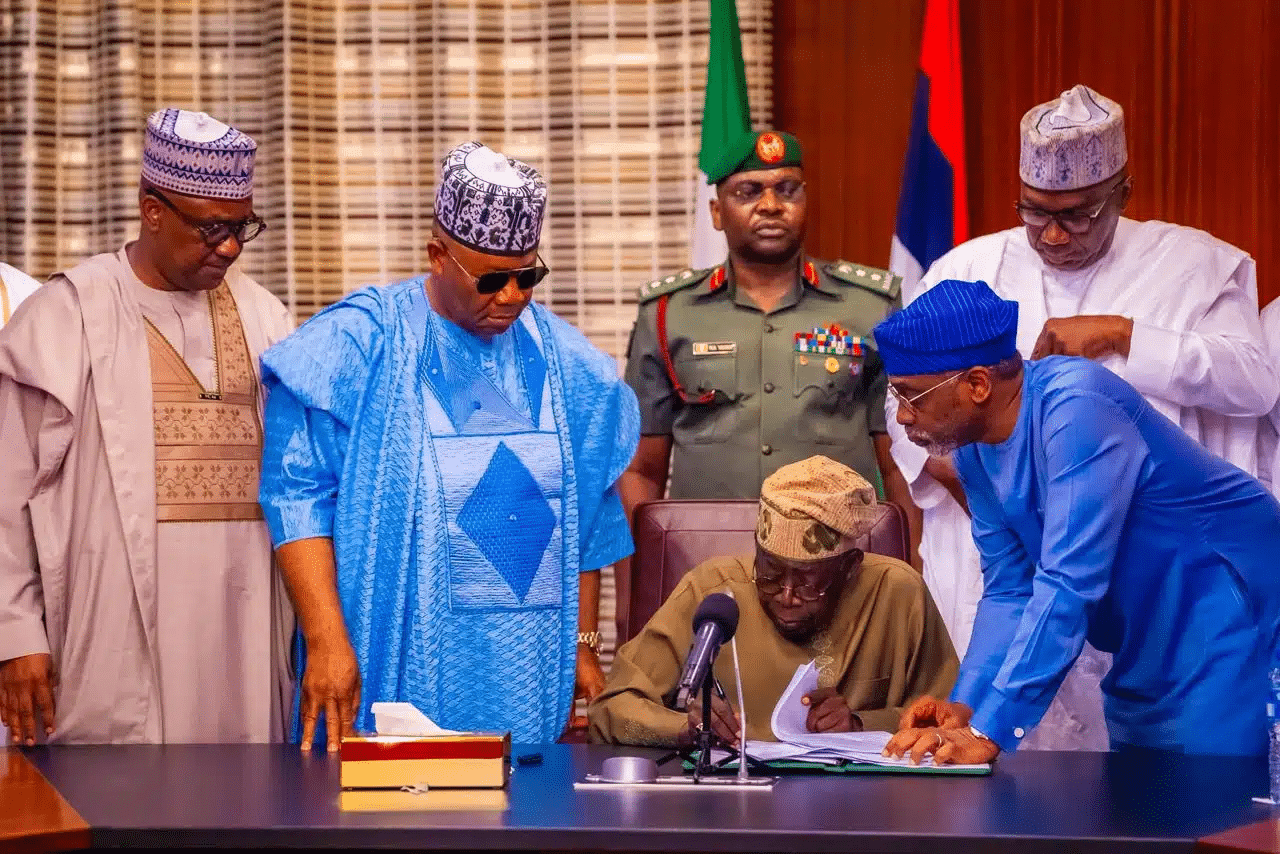

A few weeks ago, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) activated the Global Standing Instruction (GSI) policy. With this in place, banks can withdraw defaulting loans from any account held by a borrower.

Someone who wants to borrow ₦10,000 ($25.79) from Access Bank, for instance, will have to sign a mandate where the bank can automatically debit any account they operate with any other bank or financial institution where their Bank Verification Number (BVN) is connected.

With the BVN in use, Access Bank will be able to recover the loan from financial institutions like OPay, Kuda, Barter, etc., where the borrower has funds. The GSI mandate also allows the lender (Access Bank in this case) to debit any of the borrower’s joint accounts.

According to the CBN, the GSI should only be used for loan recovery and not for the collection of any penal charge which may come when a borrower defaults on a loan.

Nigeria’s Apex Bank states that this move is geared towards improving lending in the economy by reducing non-performing loans in the banking sector.

Recall that in 2019, the CBN ordered banks to increase their lending portfolio (loan-deposit ratio). Coincidentally several Nigerian banks began offering personal loans at very competitive rates.

Preamble to lending in Nigeria

Before this order, lending in Nigeria has been historically low. Chinedu*, a small-scale fashion designer says it was better to save up money for years, get from relatives, or join a cooperative when he was looking for business capital.

As of 2017, Enhancing Financial Inclusion(EFInA) stated that only 5.3% of Nigerian adults had access to credit. The International Finance Corporation then predicted that several Nigerians could become poor without access to credit, a very important part of financial inclusion.

But the reasons for this were embedded in the fabric of Nigeria. Thirteen years after the introduction of the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC), the country still lacks a central identity database. The BVN only has records of 45 million people — just 23% of Nigeria’s estimated population.

Even with the BVN, it was difficult to determine several people’s credit history. A high level of unemployment and an unstable economy constantly facing inflation and devaluation probably kept banks away from unsecured loans.

Noticing this gap, several digital platforms began offering collateral-free personal loans. They became so rampant that several of them began to engage in noticeably predatory practices.

Exorbitantly high interests, short repayment terms, and embarrassing practices (like calling friends and family) to recover loans.

Banks created their digital platforms, and their lower rates seemingly brought some relief to those in need of personal loans.

Like other fintech sub-sectors, the competition between banks and fintechs looked set to favour consumers.

The banks and regulated fintech platforms were able to access prospective borrowers’ credit history by using credit reference bureaus to check if a borrower had any other active loan.

However, lending to the retail sector only slightly improved. In January, Adedeji Olowe, a fintech expert, predicted that banks would not improve lending to the retail sector.

But no one knew exactly what was going to happen.

The pandemic

The lending sector in Nigeria has been heavily affected by the onset of the pandemic. This is not surprising given the massive economic effects it has had in Nigeria so far.

Though SMEs were granted some reprieve from their existing loans, a lot of people with personal loans sought loan relief as most platforms did not reschedule personal loans.

The risk for more non-performing loans became more glaring.

The GSI: A legally ambiguous directive

There have been several discussions about the CBN’s right to give such guidelines regarding loans.

Kemi Pinheiro, Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), believes that the guidelines are somewhat beyond the powers of the CBN.

Under the country’s laws, the CBN has the right to regulate how banks carry out their transactions. But Pinheiro argues that the CBN has no right to regulate contractual agreements — such as a loan — between a bank and its customers.

Based on other sections of the law, he also argues that only the Nigerian courts should determine the liability of a customer. In Pinheiro’s opinion, the GSI guidelines seem to be usurping of the powers of the court.

Given the CBN’s powers to regulate how banks carry out transactions, there are still some unanswered questions.

However, Enyioma Madubuike, tech lawyer and Techpoint Africa columnist, asserts that arguments could be made on both sides.

According to Madubuike, a loan, like several other banking transactions, falls under the apex bank’s purview.

“The history of the CBN’s regulations is to tell banks to do something and make it clear in their terms to the customers. It will be clearly stated that the bank will do XXXX and the customer will do XXXX,” he says.

“You could look at the GSI as a database managed by the CBN, through NIBSS, with banks and other financial institutions acting as agents,” he explains.

“The new directive is similar to the previous one. Debit my account if I fail to pay as and when due, only this time, add any of my other BVN linked accounts to the contract.”

Madubuike believes this could be the CBN’s way of gradually building a credit culture where banks would be more confident to give loans to customers.

As for the provision to debit joint accounts, Pinheiro infers, based on the decision of other cases, that “a joint account cannot be subject to a garnishee order for debt by one of the parties.”

Madubuike asserts that while this is true, the other side of the equation is that joint account holders are jointly and individually liable.

“The only problematic case is when the non-defaulting party is the main contributor to the funds in the joint account. Then, it will have to be resolved in court,” he explains.

How do fintechs factor in?

It is not clear how much fintech companies factor in with the new guidelines. Throughout the document, the CBN mostly refers to banks as borrowers, and it’s not clear if digital lenders like Carbon, FairMoney, and others would be able to execute a GSI mandate.

“We are still studying the document to understand all its ramifications, and right now, you know as much as we do about it,” says Chijioke Dozie, Co-founder of Carbon, a fintech lending company.

It is important to note that with the rise of fintech lending platforms, predatory borrowers also became rampant. Most of them borrowed from different loan platforms without paying back.

According to a former senior executive at OKash, most of these lending apps could not afford credit reference bureaus.

How Voyance wants to tackle the menace of fintech fraud in Nigeria

Platforms like Voyance are working to help fintechs arrive at a solution, but as we stated, it has to be hand in hand with banks and the country’s financial regulator.

Asterisk (*): Not real name

Featured image credits: ccPixs.com Flickr via Compfight cc