Thinking long and hard about an idea instead of just executing it makes me complicate things. The picture gets so big that I, sometimes, lose track of the point and shelve it. That is until moments of necessity, like writing a relevant Independence Day story. Then, I have to get it done.

As I write this piece, soothed by a squeaking industrial fan from the sitting room, I can’t help but draw parallels between my ideating process and the startup cum regulator relationship in Nigeria.

With a terrible ease of doing business score from the World Bank as evidence, running a startup in Nigeria involves more than drinking water and minding your business. Dr Ola Brown, the founder of Flying Doctors Nigeria, once stated that African founders have to deal with market forces (which is their business) and evil forces such as policies and infrastructure which shouldn’t be too much of their business.

Each painful circular or press statement from different authorities keep showing the need for constant engagement with regulators. But this is not so simple; the deeper you go, the more complicated it gets. That much you will learn as you read on, and you should.

On May 14, 2021, TechCabal reported that founders, investors, and government representatives are discussing a Startup Bill for Nigeria. This move came a few months after some troubling regulations like the ban on motorcycle hailing platforms in Lagos, and on cryptocurrency transactions in the country’s financial sector.

But more on this later. Please permit me to take you on a little journey. If you wish, you can skip ahead to any of the talking points you might find interesting.

Table of Content

- What does a startup act mean?

- How countries across the globe develop policies for startups

- The impact of startup acts in African countries

- Nigeria’s startup friendly policies

- Key details about Nigeria’s proposed startup act

- Very important observations

- What some experts think about it

You see, the world of startups is fast-paced and exciting. But regulators who keep playing catch up do not come with a friendly tap on the shoulder. Think Chiellini’s pull on Saka at the Euro 2020 final.

The Verge’s story of Judge William H. Alsup, who taught himself to code to settle a case between Oracle and Google, spotlights this struggle between innovation and regulations, even in developed economies, with Judge Alsup as the outlier.

Digital economy expert, Titi Akinsanmi, believes that this “move fast and let regulators catch up” game has its good and bad sides. But in the absence of well-structured policies and quality engagement, the bad sides emerge more often. The solution? Startup acts.

What does a startup act mean?

A startup act is a piece of legislation meant to create an enabling environment for high growth technology-enabled businesses, i.e. startups. It aims to create a framework that helps solve problems around funding, infrastructure, and uncertain policies.

Very few countries globally have enacted startup acts, and it is usually adopted by smaller countries looking to foster a thriving economy.

Considering Nigeria’s history of policy somersaults, an actual law that harmonises different policies and helps startups thrive seems like a no brainer. Who wouldn’t love government salaries for founders and tax breaks for eight years, as found in Tunisia’s Startup Act 2018?

First, let’s take a closer look at how countries have been approaching startup policies.

How countries across the globe develop policies for startups

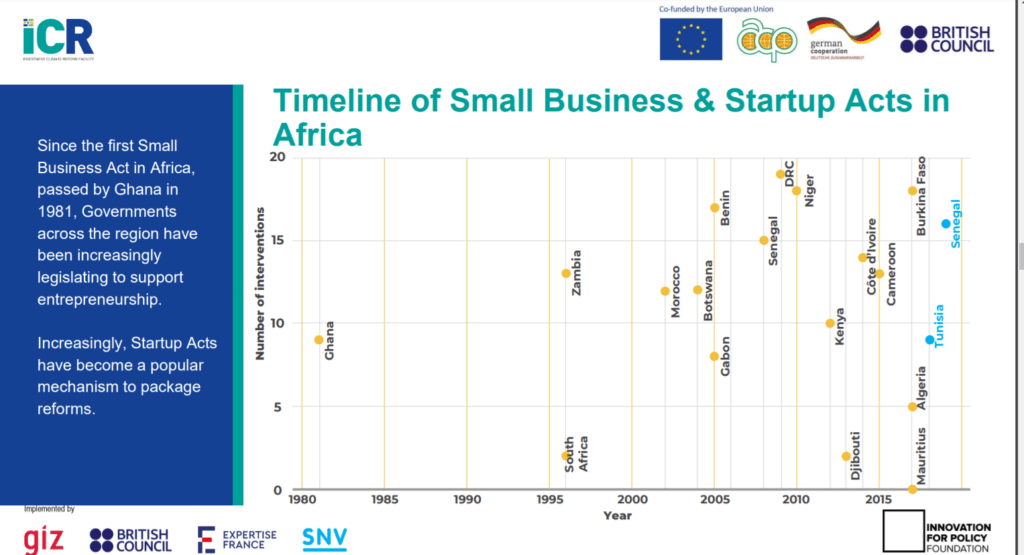

From all indications, startup acts are an innovative progression from small business acts enacted by countries in the 20th century to support Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs).

While the United States enacted a small business act as far back as 1953, policies to support high growth entrepreneurs appeared in countries like Finland, Scotland, and the Netherlands in the early 1990s.

Laws that generally contain startup-friendly policies have been the norm, with notable examples in France, India, and Israel.

Italy was the first country to enact a startup act in 2012, and it remains just one of three countries outside Africa to have done so. Others include Argentina (2017) and the Philippines (2019).

Like the rest of the world, Africa has not had many laws targeted at startups. Ghana led the way with the Small Business Act in 1980. Sixteen years later, South Africa and Zambia followed suit. Tunisia and Senegal enacted startup acts in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Besides clearly defining what a startup is, Tunisia’s Act provides several incentives such as an eight-year tax break, salaries for founders in the first year of running the startup, one year of leave for employees looking to start a business, and exemptions from capital gains tax for investors.

Note: Tunisia labels a business a startup if:

- The company has not existed for eight years or more,

- The number of its employees is not more than 100,

- More than two-thirds of its shareholders be founders, angel or hedge fund investors,

- Have an innovative business model, preferably technologically based, and

- Its activities significantly contribute to economic growth.

The impact of startup acts in African countries

Tunisia and Senegal have seen their stock rise with the media and researchers since the enactment of their startup acts. The Act is still taking shape in Senegal, so I zoomed in on Tunisia.

In 2021, the Tunisian government revealed that 500 businesses (PDF in French) have received the “startup label” and are entitled to incentives. Marketplace (online retail) and business and software services startups dominate the list, followed by edtech, healthtech, creative industries, and fintech.

Side Note: The report was filed by Smart Tunisia, a management company responsible for implementing the National Startup Tunisia Initiative, including the country’s Startup Act.

Interestingly, the report states the law has boosted revenues and funding activities (PDF in French), with more foreign startups setting up in Tunisia.

The startups cumulatively generated a $23 million turnover in 2019, and those that earned revenue in 2018 and 2019 saw an 80% increase in revenue. Half of the startups witnessed revenue decline in 2020, but the other half could generate $25 million in revenue.

In 2019, the Tunisian government reported that these, primarily early-stage, startups raised $21.8 million. In 2020, the pandemic halted several funding activities, but the startups still raised $23.2 million.

While this number might seem small compared to what’s being raised by the big four — Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, and South Africa — it is a marked improvement from previous years as the total funding Tunisian startups raised before 2019 was $18.7 million.

It is important to note that angel and venture capital investments form a small part of Tunisian funding activities. In 2019, it was just 11% but increased to 36% in 2020.

Two years on, it is still baby steps for the Tunisian space, and it seems there’s still some work to be done. However, the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute ranked it second in Africa and 40th globally for its entrepreneurial ecosystem, and 19 foreign companies have set up shop in Tunisia since the Act.

An interesting feature of Tunisia’s lauded Startup Act is that it featured contributions from experienced entrepreneurs and investors in its tech ecosystem. Other countries like Rwanda, Ghana, and Cameroon are working to enact their startup acts.

Nigeria’s startup friendly policies

To date, Nigeria only has one specific law that directly supports small businesses; The Small and Medium Scale Development Agency of Nigeria (SMEDAN) Act, 2003. The agency’s mandate is to foster the development of MSMEs in the country. It’s not clear how effective this agency has been though, as several Nigerian businesses operate away from the law’s gaze.

However, it has several laws that support the growth of startups in Nigeria. The issue so far has been lax implementation. But I’ll get back to this. Let’s check out what some of those laws are.

First, there’s the Venture Capital Incentive Act 2004. It offers several tax incentives for venture capital firms to invest in innovative companies and to support research.

Side note: If you know any Nigerian startup or VC in 2004 and that this law existed, please reach out to me.

Under Nigeria’s Companies and Allied Matters Act 2020, it has become way easier to set up a VC fund with limited partnerships. You can read more about it here.

Nigeria’s Finance Act 2020 exempts early-stage SMEs/startups with revenue of less than ₦25 million ($60,729) a year or ₦2 million ($5000) a month from paying tax.

Timi Olagunju, Tech Lawyer and policy consultant, argues that this law does not necessarily help high growth startups.

“How many startups generate less than that amount in a year?” he asks. “It’s revenue, not profit. Maybe it helps just the very small ones that are just starting. It doesn’t help many of the well-established startups we know.” he adds.

To be fair, some less than a year old startups we’ve featured already process numbers higher than $60,000 a year in revenue. However, kindly take note of this provision if it applies to you or to someone you know.

Nigeria’s Industrial Development (Income Tax Relief) Act (IDITRA) has the Pioneer Status Incentive, where first-year companies in critical industries are exempt from paying tax for possibly up to five years (three years initially and renewable for an additional two years).

To date, only one ICT company has been given this tax relief, and the Nigerian government said it denied Flutterwave entry earlier this year based on a late application.

Nigeria also has several tax relief programs, but the process for getting this is pretty tough. Like really tough.

“To be candid, most of these exemptions are at the discretion of the President; they are more often than not given on a man-know-man basis,” said Enyioma Madubuike, Lead Partner at Lawrathon.

Besides incentives, Nigeria has ICT related laws and regulations like the Cybercrime Act and the Nigerian Data Protection Regulation (NDPR). Others like Intellectual Property laws to protect startup ideas, brands, and trademarks are grossly outdated.

Nigeria’s proposed Startup Bill seeks to harmonise these existing laws and provide relevant innovation-friendly updates that would boost startup activities in the country.

“Let us begin to show the government the type of laws and policies we desire for our businesses to thrive, rather than content ourselves with bearing the brunt of old laws and a toxic business environment,’ said Enyioma in 2018. A view which he affirms that he still maintains to date.

Key details about Nigeria’s proposed startup act

Roughly six days after TechCabal’s publication, the website for the Nigerian Startup Bill went live. Per Whois.com records, the website is registered to Osaretin Oswald Goubadia, the Special Assistant to the President of Nigeria on Digital Transformation.

It contains a timeline of activities that start from the production of the first draft in June 2021 to October 2021, when the bill is to be submitted to the President, who is meant to present it as an executive bill to the National Assembly. (It’s October 1, already. So, anytime now people).

The website allows any visitor to contribute to the policy-making process, and it places calls for volunteers in the communications, research and drafting, and stakeholder engagement teams

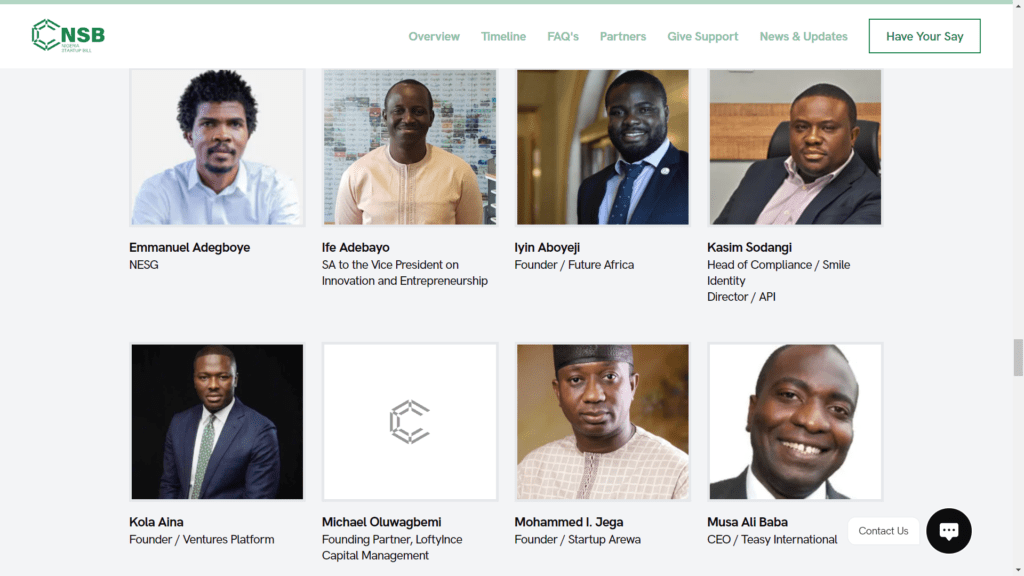

Borrowing a leaf from Tunisia, the proposed Bill is ecosystem-led, and it features prominent startup founders, CEOs, and policy experts in the Nigerian tech space.

Interestingly, the website features community stories across the country. From August 2021, the organisers began to hold town hall meetings in different geopolitical zones in Nigeria.

Very important observations

The new Startup Bill features a 16-person Presidential Advisory Strategic Group with members of the government, industry giants and policy experts. Are you pondering what I’m pondering?

This takes me back to Monday, June 11, 2018, when Nigeria’s Vice President Yemi Osibanjo inaugurated a 50-man advisory committee on technology and creativity, shortly after his famous visit to Silicon Valley.

It featured, you guessed it, heads of government agencies, industry giants, and policy experts. However, it is worth noting that four members from the 2018 committee are in the current advisory group. They include:

- Kola Aina Founder / Ventures Platform

- Iyin Aboyeji Founder / Future Africa

- Mohammed I. Jega Founder / Startup Arewa

- Sanusi Ismaila Founder / CoLab

To date, we are still asking; what happened to the Presidential Advisory Committee of 2018? Okay, let’s move on for now.

The startup bill also features support from Nigeria’s major government regulators and agencies. They include:

- The Federal Ministry of Communications and the Digital Economy,

- The National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA),

- The Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), and

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

Three things stick out for me, like a sore thumb in this lineup. One is the glaring absence of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) from the list. While these bodies may be engaging the apex financial regulator behind the scenes, history does not look favourably on this.

For context, look no further than the CBN’s recent ban on cryptocurrency transactions, just five months after the SEC recognised crypto and declared its intention to regulate the space.

Want more context? Then consider the apex bank’s decision to freeze accounts belonging to Chaka, Bamboo, and Risevest, just months after SEC announced a new licence category for digital sub-brokers. One that Chaka acquired to great plaudits. Need I say more?

The second pain point for me is the website does not detail how state governments factor in. Hear me out.

Nigeria might be a federal state with federal laws, but implementing those laws always comes with issues at the state level. Telecom companies have long experienced this bitter reality when installing towers and fibre optic cables in different states.

Two years after implementing a new minimum wage, up to ten states are yet to implement it. So, just putting it out there.

Finally, and perhaps the most glaring sore point, is NITDA, which came under intense scrutiny in August 2021 after amendments to a leaked NITDA Bill showed significant threats to startups.

Our reporter, Ogheneruemu Oneyibo, dug up what probably went unnoticed; those provisions already exist, and the amendment was to give the ICT regulator enough powers to implement sanctions when needed.

There have been thought pieces on how the Nigeria Startup Bill will harmonise existing laws. But there’s a significant question to be asked. How much of Nigeria’s fragmented regulatory structure can be harmonised with one Act?

What some experts think about it

Most of the people I spoke to while researching this story seem to think — with a healthy dose of scepticism — that the proposed startup act looks to be a step in the right direction.

Femi Aiki, CEO of Foodlocker, insists that this is the next necessary policy step.

“Given the level of unemployment, poverty and insecurity in the country and the general unease of doing business, we have to create a means of facilitating job growth and prosperity through investment. Without GDP growth, there will be no jobs.”

For him, GDP = Government spending + consumer spending + private investment + (export – import).

Aiki also argues that startups are potent tools for job creation. He says that foreign investments can help even though poorly researched policies constantly choke them.

Rita Anwiri, Chief Convener of the Intellectual Property Society of Nigeria, maintains that a startup act will have its pros and cons in the Nigerian context. Besides other benefits we’ve mentioned before, she believes it helps startups leverage the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement

“The need to have a proper structure with a Nigerian and African standard to be able to access the #OneSingleMarket of over a billion people cannot be overemphasised.”

On the flipside, Anwiri believes this same Act could stifle innovation if it’s not adequately drafted and all relevant government parties are not carried along.

“With our intellectual property laws not updated, it could hinder startups from attaining their full potential. Nigerian startups have mostly chased funding and cared less about IP rights, but a Startup Act should look to change that,” she adds.

As the ecosystem grows, issues like the Google vs Oracle story referenced above will start creeping up, so here’s why we should start taking IP rights more seriously.

Moving on, Deji Sarumi, Startup Advisory Partner at Tech Hive Advisory, admits that the country’s inherent issues, or forces of evil as it were, led to a clamour for such laws that will unify existing laws that affect the tech ecosystem. Though he commends the steps, he has some reservations.

“We have a plethora of enabling laws and regulations that could aid startups and big corporates alike, but these laws are largely dormant due to non-implementation. This could be another case of putting the chicken before the egg,” he warns.

“Our legislative system is one where ideas and bills are passed but get lost in the myriad of fragmented systems, thereby leading to little or no impact on the economy or ecosystem for which they were created,” he adds.

Echoing this view, Olagunju points to the recent ‘body language’ from the regulators — dating back to the infamous Lagos okada ban — as good reasons to exercise caution.

“If the foundation is destroyed, what can the makeup artist do? A startup act is great, but it will be a powdered approach to the core foundational issues we face if we don’t have conversations with the startup community on the current laws and policies,” he offers.

“When we see a commitment on our existing policies, then we can now start having conversations about the Startup Bill”.

While asking hard questions on implementation, both Olagunju and Sarumi are wary of using the Startup Act for vanity metrics.

“These questions are necessary so as to avoid painting a shiny picture to gain index ratings and accolades while the main issue (growth of the ecosystem) remains unresolved,” says Sarumi.

“They will just use us to score political goals. They will say they’re the ones that gave us a Startup Act when campaigning for elections, while nothing is being implemented,” Olagunju warns.

As Victor Ekwealor, former Managing Editor, TechCabal advised in 2020, “Regardless, it is important to note that a startup act is basically a mould for proper regularisation, and not a panacea for all the startup ails on the continent; it’s just a start.”

“It is the next necessary step, but I do not trust the guys ruling Nigeria today.” Aiki states. He, however, believes that building transparent measures for the process will prove effective.

Piggybacking on Femi Aiki’s assertion and the measures put in place so far, an ecosystem startup bill looks like a final trump card for the Nigerian startup ecosystem, and it has to work. It simply cannot afford to fail.

So what do you think, dear reader? Is the matter that complicated, or am I overthinking it? Most importantly, is this the next step for Nigerian tech, or do we enforce what we already have?

Thanks to those who stayed to the end and to those who skipped through the content.

Happy Independence Day!