Editor’s note: All figures quoted in this article are sourced from publicly disclosed funding announcements. While Techpoint is aware that some of the featured startups have raised more funding than announced, we have kept this information private at their request.

This article was published in 2019.

Twice a year, a certain US-based seed accelerator invests $120,000 each in startups across the world selected for its programme. The startup founders go on to relocate to Silicon Valley for three months to work intensively with the accelerator.

Each of the cycles culminates in Demo Day, an event where the startups present their companies to a carefully selected, invite-only audience to access support, mentorship and unlock further funding.

In exchange for all of these, the accelerator only takes 7% equity off the startups selected for its programme. In case you’re wondering, the above accelerator model is typical of no other than Y Combinator (YC).

YC is widely known for its activities in the areas of providing ventures across the world with early-stage seed funding. Its earliest investments were typically in US startups and understandably so. But over time, the accelerator has extended activities outside of the United States.

An interesting development though is how African startups have grown in appeal to Y Combinator. And one country seems to have the highest placement.

Nigerian startups are dominating YC’s Africa shortlist

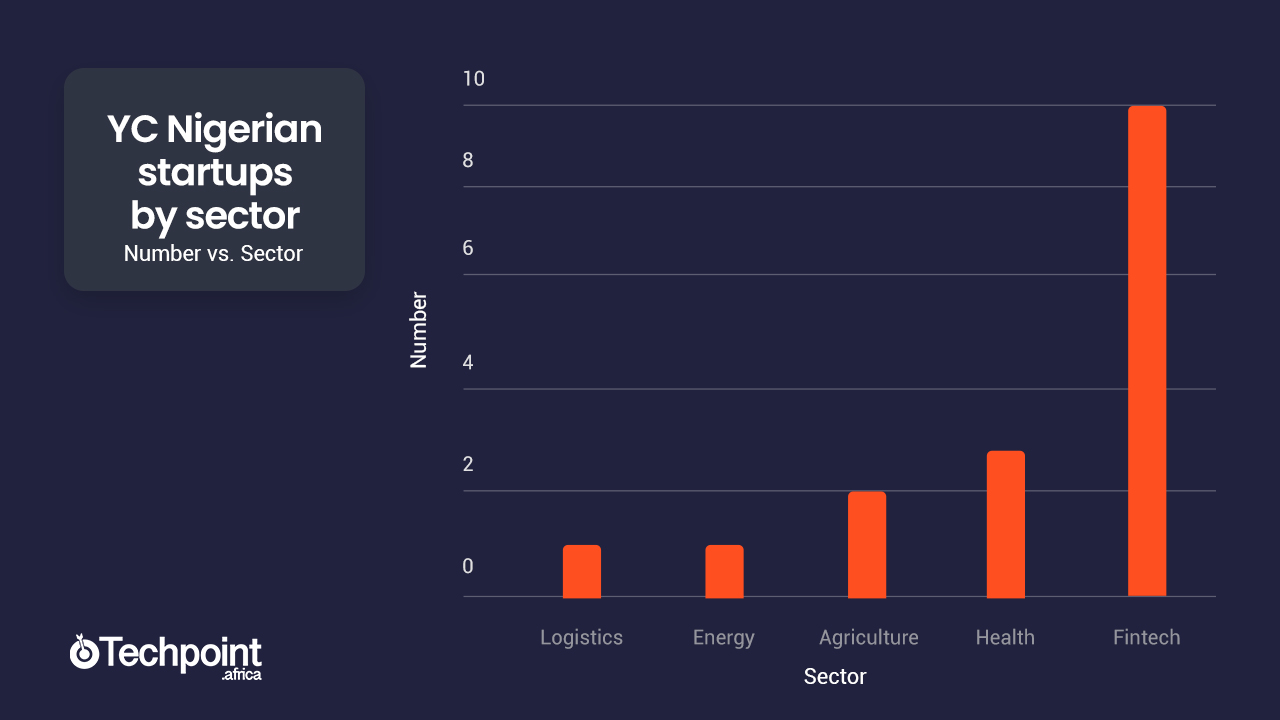

As of press time, 30 startups in Africa have taken part in YC’s acceleration programme. These have come from eight countries. And in what seems like domination of the shortlist, Nigeria — with 18 startups which also translates to 60% representation — has had the highest number.

The country’s imprint on YC took off in 2016, when Paystack and Flutterwave were the only 2 of 5 startups to be selected from the same country.

In the following year, in which Africa had its record appearance of 10 startups in YC, seven were from Nigeria. Astonishing as that is, it is nothing like the 2019 cohort where six out of seven startups selected for the prestigious programme came from Nigeria.

So is there something about YC that is capturing Nigerian businesses or is it simply a case of the startups being more certain about YC than other accelerators?

Henry Chibuzo, co-founder of YC-backed Nigerian startup Schoolable, says being with the accelerator “is like standing on the back of giants.”

Far from any exaggeration, a quick look at prominent YC-backed companies would make any startup drool: Airbnb, Cruise, Reddit, Twitch, Coinbase, Instacart, HumbleBundle, Dropbox, the list goes on.

These companies have benefited from YC’s mentorship, branding, quality partnership, meaningful investor relationship and, ultimately, funding. Like them, Nigerian startups are increasingly seeking a good mix of the same elements that have made a success out of those companies. But are the alternatives to YC not equally as good?

“Same same” predominantly YC affair

From a funding perspective, YC edges its counterparts. Only eight out of its 30 African portfolio startups have not received additional investment after YC’s standard $120,000 seed round, while another 12 have raised above the $1 million mark in total funding.

Topping that chart are five Nigerian startups — Flutterwave, Paystack, Kobo360, Tizeti and Kudi — with $20 million, $10 million, $7.3 million and $5.1 million total rounds respectively.

Combined, YC-backed African startups have raised the sum of $65.5 million in funding. In comparison Techstars, also US-based, has invested in 20 African startups but has less influence in terms of funding raised.

It’s a similar case with 500 Startups, another global accelerator, which made its entrance into Africa the same year as YC. Its portfolio companies from Nigeria, seven in number to be precise, have only managed to raise a meagre $1.3 million combined.

In one case, a 500 Startups alumnus, who asked not to be named, noted that the time spent with the accelerator broadened their network in Silicon Valley, albeit not as effective as YC in terms of fundraising.

“Compared to other accelerators, YC guarantees high-quality influence with Silicon Valley investors, personalised support in fundraising efforts and direct commitment into post-accelerator rounds,” they say.

That sentiment is shared across board as there is an increasing trend of African founders getting admitted into the many accelerators across the globe, only to later join YC when opportunities open up.

“It’s like knowing you want to study medicine at the university, and only get something close. But as soon as the opportunity for medicine shows up, you waste no effort in grabbing it,” says Ayobami (not real name).

It’s hard to miss the prospects of YC that make it a preferred destination among African startup founders. As Lindsay Wiese-Amos, a YC partner, explains it, “there’s always someone two steps in front to help guide founders every stage of their business regardless of the industry.” But still, one can’t help to wonder if most are optimising their business model solely to attract the accelerator.

It’s a capital game

The first possible hint to this came two years ago when Paystack organised a Y Combinator Lagos Meet up to help people get into the accelerator.

Iyin Aboyeji, YC alumnus with Flutterwave, who appears to have all the answers on how to get into YC, recently also has been benevolently advising female-focused teams that want to get into the accelerator.

There’s also a rather more baffling speculation that local accelerators might be grooming their portfolio startups to be YC-ready. All of these beg the question of whether there is an existing YC template that allows express entry into its prestigious programme.

Henry’s theory is that all foreign VCs (not just YC) want to see a startup that has a bottom-up approach.

He defines the bottom-up approach as a business with good enough active customers for a particular type of market, able to generate substantial amounts in revenue. And if injected with a specific amount of capital, realistically it should be able to turn in a specific number of customers in a predetermined time.

“Incidentally, those are the kind of businesses YC funds. So when people optimise from a bottom-up approach, it immediately looks like they are building for YC, but in reality they are building to attract foreign VCs,” he says.

This may explain YC’s apparent preference for fintech startups, which are inherently bottom-up.

It is equally telling that this is a game where participating startups follow the capital, for the most part.

A typical illustration is if the federal government announces that it is going to make power modular. What you’d see is that a lot of startups would start building modular power plants and products.

Another illustration is with Kudi, the fintech from Nigeria that raised investment from Partech, an Africa-focused fund. With more funds like that, people may start building solutions that those kind of VCs are targeting.

Implication(s) for the local ecosystem

As highlights of the funding activities in Nigeria have shown, most investments come from international investors. Incidentally, Techpoint’s annual funding report for 2018 ranks YC highest on the list of investors that participated in more than one funding round. This is evidence of what founders consider priority when going after the accelerator. But could the stakes be really too high?

“Local entrepreneurs meeting investors in foreign markets for a business that primarily serves African consumers is a hard game,” says Eghosa Omoigui, whose company — EchoVC — has spent the last decade sourcing and investing capital into early-stage local founders.

One possible danger is abandoning the needs of the business at the home front while the founder is away in a foreign country trying to raise funds. The scenario is similar with YC founders relocating to San Francisco for three months duration of the programme.

Zachariah George, co-founder and Chief Investment Officer at Pan-African accelerator, Startupbootcamp Africa thinks such mechanism — that demands founders leaving the needs of their businesses all in the name of seeking scale — isn’t in the best interest of local startups.

“Does it help from a traction perspective if they (local startups) go all the way to Silicon Valley when their business is not situated there?” he questions.

The question is even more baffling considering that one of the biggest challenges local founders face is the inability to access distribution networks to enable scale — something local institutions like banks, telcos and most corporates seem to have answers to.

Perhaps this is why Zachariah is convinced in his opinion that the single biggest value add-on startups could get from an accelerator is the corporate/startup linkages.

Ironically, when asked what the biggest value of YC is to startup CEOs, co-founder Michael Seibel says it’s “community”.

“Doing a startup is hard, so having a batch of fellow founders you can talk to when things aren’t going well and get support from is very important,” he buttresses.

In a different thread, partner and admissions lead for YC, Dalton Caldwell recently tweeted that the speed at which founders move is the single most predictive variable of if a startup will go on to succeed.

These follow the reasoning that funding isn’t a good metric to judge the success or scale of startups, despite local founders’ obsession with YC for funding sake.

Keeping the home front protected

Saying one is a YC founder may no doubt open doors in terms of funding, access, collaborations and partnerships. But on the streets, behind closed doors, and within the corridors of power is the silent questioning of how these impact the local ecosystem.

Which is why for Eghosa, local knowledge input to innovation is critical to the survival of startups, as has been demonstrated in the West long before now.

“There is only a handful of our local startups that YC or any foreign accelerator can fund. What’s also amusing is that some of them have never been to Africa,” he adds.

According to Eghosa, the risk associated with getting funds from foreign accelerators is high. Hence the need for more local funds to be available for founders.

“But before any of that happens, the structures to guarantee requisite support for local entrepreneurs must be in place,” remarks Kayode Oyewole, Head, Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Ventures Platform.

Ironically, one of the ways that will happen is when local founders funded by YC — or other foreign accelerators — now have enough angel money to put into other smaller businesses; thereby invariably making more capital available to early-stage local startups.

It is not unknown for these kind of interventions to boomerang, possibly creating situations worse than the original problem. But Henry believes that, like every evolving economy which has had to pass through that phase, the trends are going to change for the better.