President Donald Trump recently signed an executive order increasing the cost of hiring foreign workers under the H-1B programme to $100,000, a move that threatens India and China’s tech talent pipelines but is expected to have a minimal impact on Africa.

The order requires companies in the US to accompany every new application to bring skilled foreign talent into the country with a $100,000 fee.

The administration claims that this will ensure that only individuals with rare skill sets that American workers cannot replace are granted H-1B visas.

The news was met with an array of opinions from global tech leaders, companies, and immigration experts and advocates.

While some expressed concern that skilled workers from the Global South would now face a significant hurdle in accessing opportunities in the US, others pointed out the possible silver lining, alluding to the fact that the new policy would inevitably cause global companies to hire more remote workers, creating an opportunity for African skilled workers to access these opportunities from home.

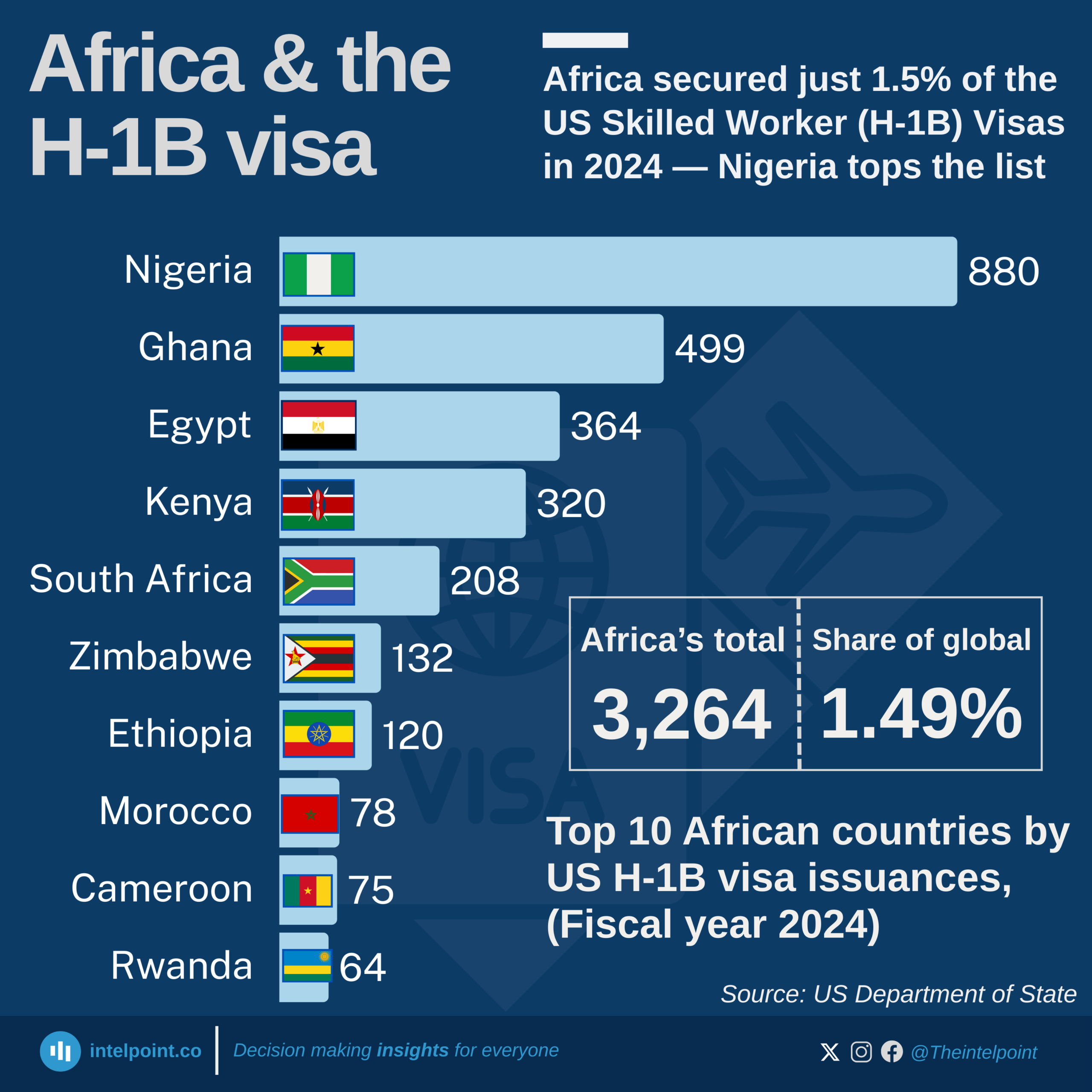

But the data shows the contrary. In 2024, India ranked first on the top ten list of countries with the most approved H-1B visas, accounting for 71% of the approvals. China came second with 11.7% of the approved applications, and Nigeria, the only African country on the top-ten list and tenth on the list, accounted for less than 1% of the approved applications. Ghana ranked 24th.

This indicates that African workers were barely benefiting from H-1B visas before Trump’s new rule and will be the least affected by it. Hence, the likelihood that global tech companies will suddenly look to Africa for remote workers as a consequence of the new policy is slim. It is more likely that these companies, which have historically sourced talent from India and China, will continue to do so.

A USCIS report on the trend of approved H-1B visas between 2007 and 2017 shows that Indian nationals received the most H-1 B visas, with 2,183,112 approvals.

China came in second with 296,313. No African country made the top ten or top 20 list. Fiscal year 2024 marked the first time an African country appeared on the top ten list, with Nigeria ranking tenth.

Victoria Fakiya – Senior Writer

Techpoint Digest

Stop struggling to find your tech career path

Discover in-demand tech skills and build a standout portfolio in this FREE 5-day email course

Trump’s revised H-1B fee may reshape global hiring, but Africa’s limited presence in the H-1B system highlights a deeper issue: until African countries can train and retain advanced talent via a revised university education system, especially in in-demand areas like artificial intelligence, the continent will remain on the sidelines of global competition.

For example, some of the companies that have most benefited from the H-1B visa in recent years and will be most affected by the fee hike are Microsoft, Meta, Apple, Amazon, and Google. Reuters reported that Amazon received 12,000 H-1B approvals, while Microsoft and Meta had over 5,000 approvals each in H1 2025

A common thread among these firms is that they are key to the US race with China in artificial intelligence. A pragmatic move to circumvent the new policy would be to shift AI research and development, which has become a key part of their operations, abroad to countries where they can access highly educated talent without a $100,000 price tag.

If this happens, African countries are unlikely to be included on that shortlist. USCIS data shows that in 2024, 41% of initial H-1B approvals and 48% of continuing approvals went to candidates with a master’s degree. Another 12% and 6%, respectively, had PhDs. And 34% and 32%, respectively, had a bachelor’s degree. This reflects the recruitment patterns of global companies, many of which have increasingly secured H-1B visas in recent years.

This is not to suggest that Africans do not pursue post-graduate degrees. However, only a few pursue degrees in computer-related courses compared to their counterparts in the US, India, and China.

For example, in the 2023/2024 academic year, graduation statistics from the University of Ghana show that of the 17,535 graduands, 2,620 (14.9%) were from the College of Basic and Applied Sciences, and only 530 of those were graduates at the master’s or doctoral level.

In a similar fashion, at the 2024 graduation of students at Makerere University, Uganda, of the 661 graduands (accounting for 5.1% of the total 12,913 graduands) from the College of Computing and Information Sciences, 32 were awarded master’s degrees and two were PhD recipients.

AI firms are aggressively recruiting individuals with advanced degrees. Fortune reported in June that newly minted PhDs are being offered multimillion-dollar signing bonuses. That same month, Wired reported that Mark Zuckerberg had assembled Meta’s superintelligence team by poaching members from OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic. Most team members hold advanced degrees from top universities in the US.

Nigeria and other African countries must build a similar pool of highly educated talent who can compete on the global stage. A White House report shows that nearly half of AI-relevant PhD graduates in the US are non-US citizens.

The report further shows that while the US produces more graduates in AI-related subjects than most other countries, India produces more AI-relevant bachelor’s degrees, and China produces more AI-relevant bachelor’s and PhD degrees. This points to why both countries have repeatedly topped the list of approved H-1B visas for over a decade: they have consistently produced talent that global companies need.

To do the same, African universities must adapt to the trend and expand beyond traditional computer science and engineering programmes. They need world-class faculties dedicated to emerging fields, with artificial intelligence at the forefront today.

Why artificial intelligence? Because that’s where global attention and investment are currently focused and are likely to remain for years. However, beyond AI, these faculties must be adaptable to whatever new fields emerge as global leaders and capable of training students to compete at the highest level.

While many universities on the continent are increasingly offering undergraduate and postgraduate courses in artificial intelligence, a major problem lies in a shortage of qualified faculty. The novelty of these programmes means that the continent is yet to build a pipeline of experts capable of teaching the subject at scale.

For Africa to catch up and supply the kind of talent global companies demand, universities and governments must harness these opportunities to build their talent.

First, they may need to recruit international experts to lead programmes in areas such as artificial intelligence, ensuring that the curriculum meets global standards. That could mean attracting professors from top institutions in India, China, and the US.

Second, African governments and universities must pursue international exchange programmes with universities worldwide that enable African students to gain hands-on experience in research environments abroad and bring those skills back home.

These strategies will ensure that, in years to come, Africa becomes a trusted hub for high-quality and highly qualified technology experts.

Until these investments are made in grooming the quality of students and talent African countries produce, workers will continue to struggle to compete with their counterparts in other countries.