On October 20, 2020, armed forces opened fire on young Nigerians gathered at the Lekki Toll Gate, abruptly ending the #EndSARS protests that had captured the nation’s imagination. For many who took to the streets demanding police reform and good governance, the violence didn’t just crush a movement—it severed their belief that Nigeria could change. What followed was a wave of departures that has yet to stop.

The timing couldn’t have been more pivotal. COVID-19 had already reshaped the world of work, making remote opportunities accessible and exposing the cracks in Nigeria’s social and economic systems. As borders reopened, countries like Canada and the UK dangled new pathways—talent visas, relocation programs, and the promise of stability. By 2022, what started as a trickle had become a torrent.

Today, the departure halls of Nigerian airports tell a story we grow weary of knowing all too well. Every week brings another round of goodbyes—families quietly sobbing at departure gates, friends gathered for yet another send-off, conversations laced with nervous laughter that thinly veil the realisation this may be the last gathering of its kind.Then follows a social media post, often the “Japa” meme from the Nollywood film King of Boys, where Eniola Salami (played by Sola Sobowale) raises a glass with a knowing smile beneath the caption: “Welcome to a new dispensation.”

“Japa,” a Yoruba term meaning “to flee” or “to run away,” evolved from a slang into a national migration strategy, particularly among young professionals who had once believed they could build something better at home. Recent surveys show that 71% of young Nigerians are considering relocation, with 85% saying they would leave if offered the opportunity.

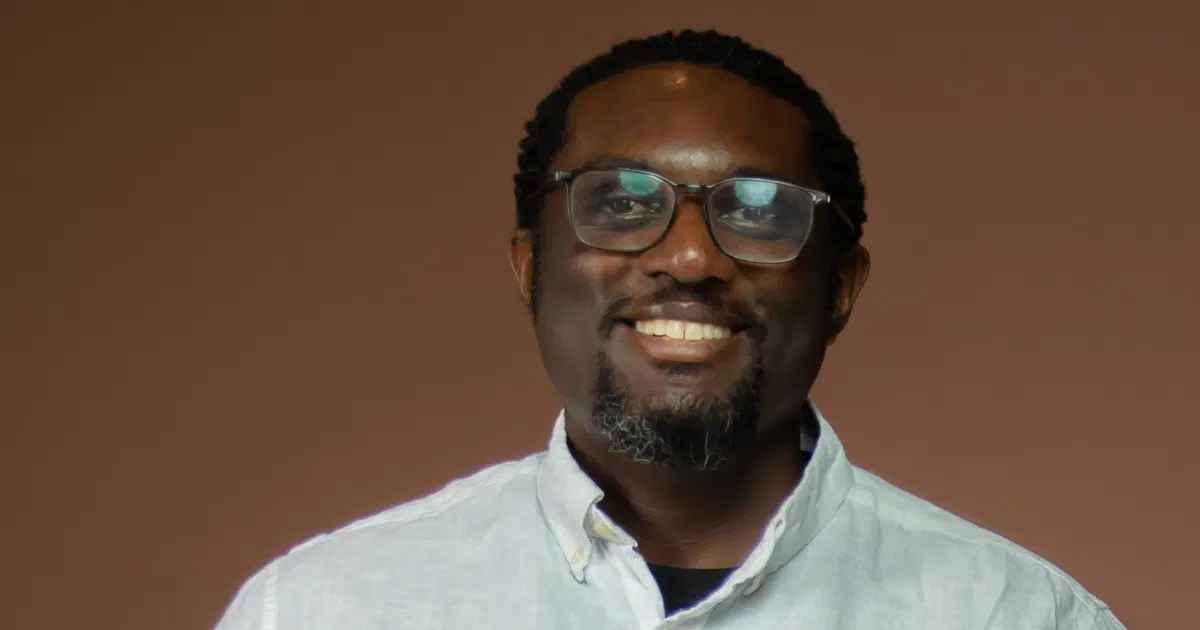

Consultancies have sprung up to meet the demand. Blaise Aboh’s Traavu Global, for instance, has seen nearly 20,000 people take its automated global talent visa assessment over the past 4 years, though only 3% qualify. The sheer scale of interest underscores how deeply migration has become ingrained in the national psyche. What began as a response to state violence and poor infrastructure has become a sustained exodus that shows no signs of slowing down.

The central question isn’t whether Nigerians are leaving, but what they’ve left behind. With each year, businesses feel the strain more acutely. A PwC report revealed that 31% of Nigerian firms have been significantly affected by the emigration, struggling with workforce gaps and disrupted operations.

The breaking point

According to a 2023 study, the drivers of the country’s emigration numbers are classified into political, economic, and socio-cultural categories, ranging from poor economic conditions and unemployment to the quest for greener pastures, the desire to obtain international academic qualifications, and security concerns.

In the early months of 2020, nearly everything changed when the pandemic struck. COVID-19 laid bare Nigeria’s fragile systems — healthcare, governance, and infrastructure alike — and, on the slightly brighter side, normalised remote work. However, it was the #EndSARS protests later that year that turned migration from an aspiration into an urgent necessity.

For many young Nigerians, the protests represented possibility, a belief that collective action could turn the tide. Those hopes fizzled when the movement was truncated by unprecedented armed violence. More than a line in the sand being crossed, the event erased it altogether, a moment many say altered their relationship with Nigeria in ways they felt could never be undone.

Victoria Fakiya – Senior Writer

Techpoint Digest

Stop struggling to find your tech career path

Discover in-demand tech skills and build a standout portfolio in this FREE 5-day email course

Joyce Imiegha, founder of Renée PR, remembers this as an event that completely shifted her perspective on remaining in the country. Her involvement in the protests became apparent after she granted an interview with CNN, prompting her family to fear for her safety.

“My family became genuinely fearful for my safety because many protesters were getting arrested at the time,” she says. Fear, coupled with the frustration of watching friends leave while she continued to navigate Nigeria’s fragile infrastructure, pushed her to relocate two years later. Now, she works as a communications manager at a UK-based company.

The economic strain only deepened the frustration. Inflation climbs while wages stagnate, forcing many Nigerians to juggle multiple jobs or run side hustles just to keep afloat. Marketing manager Oyinlola Akindele says it candidly: “If you’re not part of the top 1%, you can barely afford the things you want, let alone even go on vacation.” For her, and for many others, the grind had simply become unsustainable.

Between 2015 and 2023, Nigeria’s national grid collapsed 93 times, leaving residents reliant on noisy, expensive generators to keep phones, laptops, and even water pumps running. The collapses have continued at the same pace since 2020. For product manager and entrepreneur Habib Wasulu, these were dealbreakers. “I couldn’t stand the noise of the generators or the endless switching on and off when electricity was restored, especially because my generator was downstairs,” he recalls. By 2022, he had relocated to the UK.

Princess Akari, a product manager, notes that the impact of becoming a migrant is almost immediate. “The moment you change your location, you automatically become more attractive to recruiters. There is constant electricity, and life is just way better, and when you send money back home, it goes a long way, especially due to the exchange rate,” she commented.

Others point to the wider horizons and opportunities a foreign zip code brings. “Relocating has helped me to see things from a global perspective. When I think about solving problems, I’m thinking about solutions that are scalable globally,” says Hackthejobs founder Victor Adeleye. For Oyinlola, it all comes down to balance: “I keep discovering new ways to grow. The options here feel limitless — there are so many possibilities, and I finally have a good work–life balance.

The ripple effects of migration

Back in Nigeria, the effect of Japa is undeniable. Organisations have been forced a rewrite the playbook on talent retention. HR professional Felix Bissong witnessed a dozen employees resign in a single year, an exodus he describes as “unlike anything I’d seen.” What they sought, he realised, was flexibility, career growth, and the promise of stability. “Losing so many talents to japa was sad, but there was nothing I could do about it,” he expressed.

Others echo the same challenge. Emmanuel Faith, another HR professional, no longer fights talent departures. “I encourage them to leave if they get good opportunities. But I ask them to stay connected remotely.” And for HR veteran Moses Joel, “When offers come from abroad with relocation support and higher salaries, it’s nearly impossible to convince people to stay.”

The most pragmatic coping approach has been adaptation. Some companies have tried offering stock options, remote work arrangements, or frequent salary reviews, but the verdict from those still managing Nigerian teams is sobering: full recovery isn’t coming.

The gap is most acute in technical and product roles, where replacing someone with 10 years of experience proves nearly impossible. “Replacements almost always lack depth, exposure, and experience,” Bissong explains. Emmanuel Faith is blunter. “Do you know how many amazing talents are now working in the UK, Canada, the US, and other European countries? From a marketing perspective alone, I can name at least ten people whose presence in Nigeria would have significantly benefitted the ecosystem.”

The migration story is not one of loss alone. Many who leave remain tethered to Nigeria’s tech ecosystem, contributing knowledge and capital from abroad.

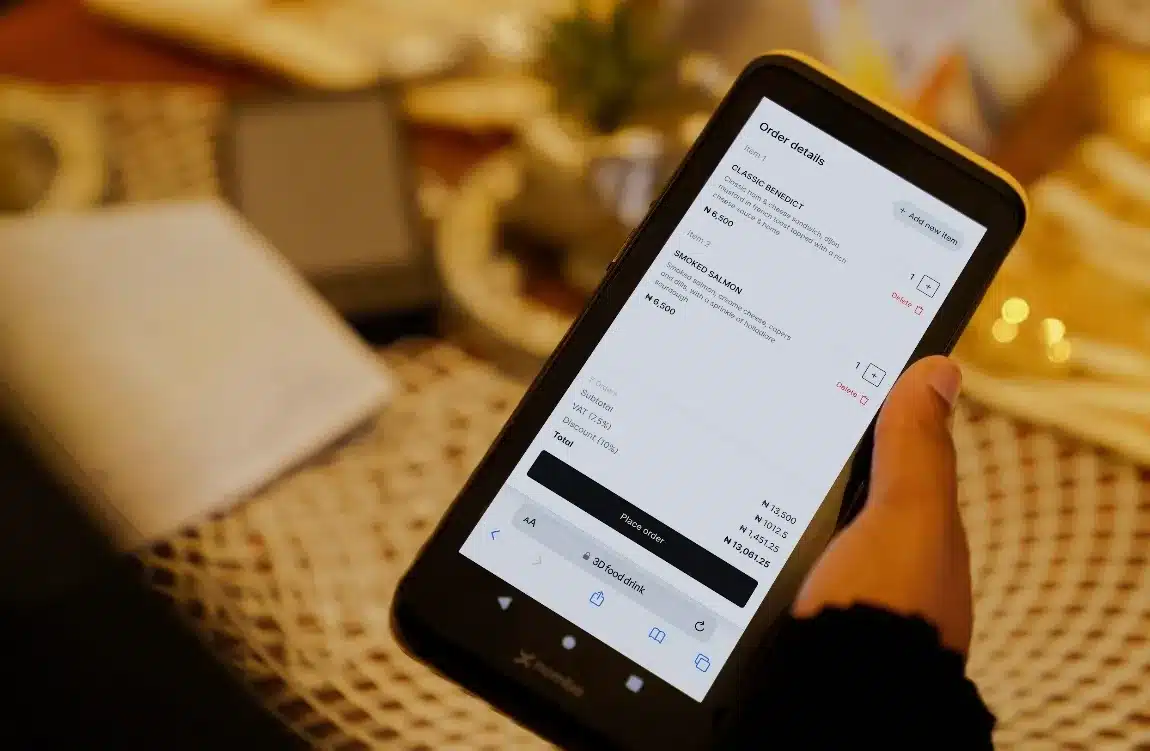

Blaise Aboh refers to this as an overlooked benefit of brain drain. “Many who have migrated are breadwinners with family obligations. They also pay black tax, a form of giving back that fuels investment at home,” he explained. The surge in remittances since 2020 is one reason cross-border fintechs have found a strong footing.

Others maintain their ties through work. From the UK, Peace Itimi continues to run Founders Connect, spotlighting African tech innovators. Organising events remotely comes with its fair share of challenges, but for her, the work has always transcended geography. “We’re always finding new stories and better ways to tell them. I don’t believe it is only about being present on the ground,” she admits.

Zap Africa founder Tobi Asu-Johnson, based in London, visits Nigeria several times a year and keeps his team engaged daily via WhatsApp and Slack. He reflects that “running the business from abroad has actually normalised frequent communication, deepened trust and strengthened team culture”. Habib Wasulu shares a similar view: “The strength of a company lies in its people. While my physical presence at Smileys Africa would help us achieve even more, we’ve put structures in place to ensure operations run smoothly — though it’s not without its challenges.”

Likewise, Ekechi Nwokah, founder and former CEO of Migo, notes that effective leadership from abroad depends on staying closely connected to on-the-ground realities. “I can’t imagine going a single day without speaking to my team. I visit often because I need to see firsthand the challenges they face — from fuel shortages to faulty transformers and other everyday hurdles unique to Nigeria,” he says.

Beyond building and investing in startups, Nigerians in the diaspora are also nurturing the next generation of professionals. Princess Akari, for instance, runs People in Product — a product management community offering mentorship, resources, and support, which she helps coordinate remotely. Likewise, Victor Adeleye, through Grazac and the Ogun Digital Summit, is helping tech professionals upskill while driving the growth of Ogun State’s tech ecosystem.

Still, individual effort can only go so far. While diaspora professionals build bridges across borders, they cannot fix the deeper systemic issues that drove them away. That responsibility lies with those in positions to create lasting change.

Policy, systems, and the way forward

The solution to Nigeria’s japa wave is not simply convincing people to stay — it’s giving them reasons to come back. This phenomenon, often called reverse japa, reflects a renewed sense of purpose among those abroad. “I have plans to move back to Nigeria because I’m still invested in building the country’s tech ecosystem,” commented Adeleye.

But passion alone is never enough. Reverse migration requires more than sentiment; it needs structure, stability, and opportunity—the kind only the government can sustain. No matter how brilliant or determined, no individual can outwork a faltering economy, pervasive insecurity, or the absence of functional infrastructure.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. Build reliable systems, and its talent will find their way home. Ignore them, and the steady stream abroad will swell into a flood. Either way, this generation will succeed—the only question is which country will reap the rewards of their brilliance.

About the authors

This piece was put together by Olaitan Kenny and Ogechi Nelson, storytellers at Reneé PR.

Editor’s note: 20:40 PM – The article has been edited for conciseness and clarity. However, the original intent and core message remains unchanged.