On certain mornings in Enugu, before the sun burns the mist off the hills, the city sounds like it is breathing differently. There’s the patient cough of the wheel loader, getting ready for another round of road construction. Large public transit buses pass. It looks ordinary, but under the hood, it runs on one of the cleaner energy sources in Nigeria today.

In a modest concrete block that once gathered dust, a commissioner welcomes the Techpoint Africa team to discuss Enugu’s ambitions. As he sat down, eyes brimming with possibilities, I flashed back to the conversation that brought us here.

“People need to feel safe bringing money into a place,” Brian Chibuike, his technical adviser, had told me the day before. “Policy, infrastructure, talent—those three have to show up together.”

Before you spend your own capital, you check the roads. You ask who is laying fibre and where the next substation is.

Enugu has always been consequential for the global energy industry. By 1916, Coal production hit an all-time high of 790,030 metric tonnes, feeding British furnaces and Nigerian locomotives.

The wager now is simpler and harder: to feed livelihoods. To turn a state that powered trains into a city that powers digital careers.

The city that decided to stay

The Honourable Commissioner for Innovation, Science and Technology, completely frames the city’s new trajectory. At some point, they said, “It doesn’t just have to be coal.”

His metaphor is direct. “Those strong and resilient people [of the coal era] have given birth to young people who are very strong mentally, intellectually… who can take us into the digital era,” he tells me. “We shouldn’t just be consuming technology, but big players in the development of technology.”

The stakes are existential. Governor Peter Mbah has set a lofty target: grow the state’s economy from $4.4 billion to $30 billion in eight years. Technology, he insists, will contribute “more than 10%” of that growth. It’s an ambition that requires not just policy changes but a complete reimagining of what a Nigerian state can be.

Victoria Fakiya – Senior Writer

Techpoint Digest

Stop struggling to find your tech career path

Discover in-demand tech skills and build a standout portfolio in this FREE 5-day email course

That ambition starts from the streets. This ministry has moved from slogan to action with the introduction of free right-of-way for fibre Internet service providers. “You can walk into the state and lay cable without being charged even a dime,” Dr Ezeh reveals.

This move is quite significant. It’s one of the biggest costs for ISPs nationwide, with some states charging as high as ₦9,000 per metre. So telcos have little incentive to deploy fibre outside of commercial and administrative hotspots.

Alongside fibre, there are roads: dual carriageways to the university, arteries out to neighbouring states—“Our approach is strategic, cause we know digital transformation is not just about sitting in one place.”

The city’s mood has shifted from “go where the work is” to “make work possible here.” That shift is visible in the small pockets of founders and operators quietly testing what a city built for the future might look like..

Together, they’re trying to prove that the coal that once fired Britain’s Industrial Revolution can be replaced by something less tangible but more powerful: human ingenuity, measured in lines of code, startup pitch decks, and technology festivals.

Talent to run businesses, and businesses to keep them

Eliezer Ajah remembers when learning computer science meant writing code on paper.

“I studied computer science in a Nigerian university. Before I finished, I wrote code on a piece of paper,” he tells me, laughing and shaking his head. Seven years later, he meets young students still doing the same. That experience left a scar in his heart.

“I think the first thing that we noticed was that Enugu had the highest concentration of tertiary institutions in Nigeria—about 30 or thereabouts,” he begins. “The second thing was that there was a dearth of opportunities where people were leaving to go to Lagos, to go to different places to find these opportunities after they had learned here.”

The ripple effects of this were being felt across the ecosystem. Joy Okoye, HR Manager at Xend Finance, one of Nigeria’s biggest success stories in Blockchain, is right at the heart of this experience. In a country where most Blockchain startups (or any startups for that matter) are headquartered in Lagos, Xend chose to be part of the ecosystem early on.

“Most of the time, the talents you find are half-baked. Getting people who actually know what they are doing and can actually do what is required on the job is a challenge,” she laments.

So in 2016, years before the current administration took office, Genesys began the work of “stopping the exodus. A training programme tailored to industry demand, not a painfully outdated syllabus. “You’re not just going to learn COBOL for the sake of it. We were going to help you do demand identification,” he says.

Alumni from Genesys landed at Microsoft and Google; others started companies and hired their friends. A loop formed.

Walk through the city, he says, and you’ll meet a twenty-two-year-old who “builds products with React” and probably learnt at Genesys or a Genesys-adjacent room. Genesys created “critical mass”—Eliezer’s favourite phrase—by turning learners into mentors into employers.

With the rise of more technical employers, you’d be forgiven for thinking that’s all you needed to run a business. Across town, at the popular Ogui road, Chinyere Otuonye, founder of Sparks Ventures Hub, is all too familiar with the pains of running a business. Her story still stings, more than a decade later.

“I decided to set up an IT franchised company in Abuja to provide training services in embedded robotics, nanotechnology, and online reputation management. Far back, 2013. That was the wrong market. That was the wrong location, and it didn’t take three years. That business just ran to the ground. Inexperienced and unethical hires made me lose contracts worth millions.”

Now, from her hub launched June 1, 2024, she’s fighting the statistic that haunts most startups: “Over 70% of new businesses fail in their first year. Only 10% in 3, and 5% in five years.”

While all three were trying to solve the talent and business development problem, they all had to tackle systemic concerns in the state. Power and, Internet were in short supply, and they effectively had to become their own government.

“We had people staying at the office. We had to buy water and backup power because the bare necessities were not provided,” Eliezer lamented.

His North Star kept him going: “Bringing out the next set of innovators that were able to drive change from where they were.”

This is the bridge from the city’s decision to stay to the people who decided to make staying worthwhile. The Commissioner’s office is now trying to do the same thing at the state scale: route around friction.

A commissioner’s wager: rules, roads and reliability

“You can’t shave a man’s head in his absence,” Dr Lawrence says. “Policy, he insists, must be co-created with the ecosystem.” The ministry’s job, as he frames it, is to make innovation and technology “the only speedy way” to scale the economy “from the $4.4 billion to the $30 billion” the administration is chasing.

His first move was human. The entire tech ecosystem. Those, like Eliezer and Joy, who had been ignored, whose letters went unanswered, suddenly had someone who wanted to listen.

“I had to bring them all on board, so I started meeting with them, not even in the office, because my office then wasn’t ready. So I started meeting with them at my house. They provide me with all the needed support to make sure I succeed as a commissioner.”

Situations like this look normal. But in a nation where government and citizens often exist in parallel universes, this was quite the interesting move. Free right-of-way so fibre providers don’t start making losses before they build. Dualise critical roads and implement modern public transit so commutes become predictable. Put credible security on the same checklist as broadband. Convene the builders, publicly, to drive synergy.

But it doesn’t end there. Independent power generation, a subnational airline, and e-governance are playing a big part.

“It has been structured in such a way that independent power plants are cropping up,” Brian notes. There’s even more political context: “We’re the third state. Only three states in the federation have gained independence to generate and transmit power on our own.”

“If you don’t have power, and then there’s this other person who stays in another part of town who has power.’ You begin to ask questions of the company serving your area.”

Transportation infrastructure followed a similar logic. “New buses, CNG buses, are now in place to ease or improve commuting in Enugu.” Brian, the HC’s technical adviser, explains. “In the next few months, 2,000 mobile CNG cars will also be deployed.”

Dr Ezeh also explains how critical the airline is: “Enugu State is the second sub-national in the entire of Africa that owns its own airline. You can now do Abuja twice in a day, unlike before. You do Lagos, Enugu, four times—you go twice, you come back twice.”

The wallet system ties it together. “It will enable you to access any of the city’s public services,” he explains: “You can also use it to access other things like cinemas and plug into other payment gateways globally.”

But perhaps the most radical transformation happened in government operations. “The Ministry here in Enugu State has gone completely paperless. We’ve gone on a full-blown e-governance structure,” he reveals.

The conversation keeps going back to inclusion and scale. “My dream is to ensure that even the ordinary woman in the market… sells to the person in Sokoto without even seeing that person,” he says—then flips the lens: government must infuse “every other ministry… with innovation and technology.”

Which left the hard question we couldn’t ignore: if all that is being done to attract talent and capital, who pays? Can the state actually execute?

The maths behind the mood

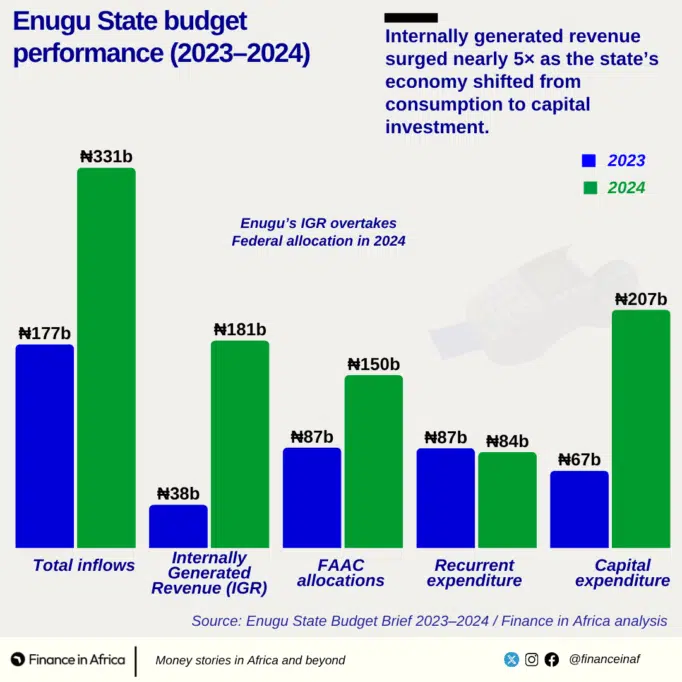

Per its budget brief, in 2023, a transitional year, Enugu realised ₦177.2 billion in total inflows (78.9% of plan) and executed 68.5% of total spend. A look at the tables will show that the government spent more on recurring expenditure ( ₦86.8bn), compared to capital expenditure (₦67.2bn).

Two numbers showed signs for the future. First, the state’s Internally Generated Revenue (IGR) overperformed at 104% (₦37.6bn), credited to technology-driven revenue collection that lifted yield by a reported 446%. Most of that capital spend came late in the year — a preview of what 2024 would bring

Then the step-change. In 2024, the revenue mix didn’t just improve; it flipped. Internally Generated Revenue jumped from ₦37.63bn to ₦180.50bn—roughly a 4.8× leap year-on-year. Over the same period, FAAC rose from ₦87.31bn to ₦150.39bn.

Enugu’s IGR outpaced FAAC by about ₦30bn, an uncommon outcome for Nigerian states. That reversal underwrites the claim that Enugu can increasingly fund its ambitions.

Execution mirrors that split: recurrent expenditure finished around ₦83.51bn, while capital expenditure posted ₦207.20bn for the year, only about half of a deliberately capital-heavy budget.

This massive growth can be attributed to plugging leakages in taxation as well as revenue-generating opportunities. In Power, transportation and financial technology and beyond.

Ambition requires capital. Massive capital. The government’s 2025 budget shows the scale of this intent.

Education would receive ₦320.6 billion—over 33% of the entire budget. 260 smart schools, one in every political ward, fully equipped with fibre optics and digital infrastructure.

Security infrastructure: ₦10 billion for high-tech CCTV systems.

Agriculture: ₦20 billion for 1,000 tractors. ₦52.5 billion for three Special Crop Processing Zones.

Numbers explain the mood, but people and the community decide whether it lasts.

Festival as an instrument, not a theatre

For policies and investments to become muscle memory and leave a lasting impact, you’d need a strong community or a group of communities that come together to plot the future. That’s where the Commissioner and his team come in with the Enugu Technology Festival (ETF).

While this is easy to dismiss as just another tech event, the thesis is simple.

“It’s less selfie, more signal,” Xend Finance’s Joy Okoye explains. “Entrepreneurs will probably say they’ve attended too many tech events, but this one is selling the vision and bringing the relevant people that matter to your business.”

South by Southwest is one of Texas’s largest creative and technology events in the world today, and in 2024, it brought about $338 million to the state’s economy. Eliezer points out that the SXSW could have decided not to start theirs because of other existing events.

“You need critical mass with things like tech events,” he says. “Do more events,” “do more trainings,” and keep the loop tight: showcase, collect five names, validate, and find the person who will puncture your fantasy unit economics before a customer does. The real thinking is to run more events of every scale until the city becomes truly tech-enabled”

May 2025. Enugu Tech Festival’s maiden edition. The original targeted audience was 10,000 physical participants.” What they got shocked everyone.

“We ended up having a humongous number of about 28,000,” Dr Ezeh recalls, still sounding amazed months later. “It leaves you with the fact that yes, the message actually sank well. And we didn’t even do a whole lot of adverts then.”

The government doubled down on efficiency with the use of homegrown products and vendors.

“We didn’t use Eventbrite or Ticket master. The festival relied entirely on Enugu-built tools—from event management by Teeketing to branding by Bluekite Consults.”

Every vendor. Every platform. Every service. Enugu-built.

“The message to investors was clear: the ecosystem is starting to offer something real, not just rhetoric. As investors, we are able to tell you, ‘These are the exciting founders you’ll be talking to.’ And we brought people like Ventures Platform to come and help us with the screening of startups so that we’re only giving the best of the best.”

Chinyere of Sparks Ventures Hub says her pride spirals from the event stage to the streets, the tourism, the food, and the palm wine, and then back to the spreadsheets where deals are signed.

The central message here is, the real product lies outside the event halls. The tech festival is the city’s pitch deck. “Come for ETF, stay for the city”. A 10-minute ride to the airport, fast Internet, reliable power, and the freedom to move around the city without fear. All within an ecosystem loop that wants to build massively in education, energy, agriculture and lots more.

The people who stayed—and those who came back

Chinyere carries the useful scars. So imagine her excitement after signing a partnership with Microsoft to keep building on what she’s already doing for fledgling startups in the Nigerian startup ecosystem. She’s seeing the impact of the renewed ecosystem on her startups and is hopeful about the fundamental potential of the state.

“The simplicity of remitting taxes goes a long way. You’re not being hoodwinked to make payments that could lead to double taxation. I left Abuja to come to Enugu. That says a lot, and I’m still here. Helping to make the city a corridor to South East Nigeria.”

Eliezer measures progress by “ease.” If the buses run and the lights hold, people can build. If the government turns promises into reality, the city will stop exporting its best. If the Commissioner keeps convening the people who used to meet in Lagos, more will come back.

Dr Ezeh’s vision is simultaneously granular and cosmic. On one hand, he obsesses over details: How much paper is left on his desk (a signal of increasing egovernance), how the drainage system or even investments in other sectors.

On the other hand, his ambition is vast: “I want to look back in the next few years to see Enugu State sourcing local talents because we’ll have them in abundance, incubating them, accelerating them, and even transporting and shipping some of them out to work in the global economy.”

His parting words echo: “We’re not looking at measuring up with other states in Nigeria. We’re looking at measuring up with all our contemporary states across the globe. That’s our target. That’s our benchmark.”

The numbers suggest the ingredients are there. The question now is whether Enugu can build a culture of execution and sustained growth as quickly as it has built a culture of hope? If the city keeps breathing like this in the morning, you wouldn’t bet against it.