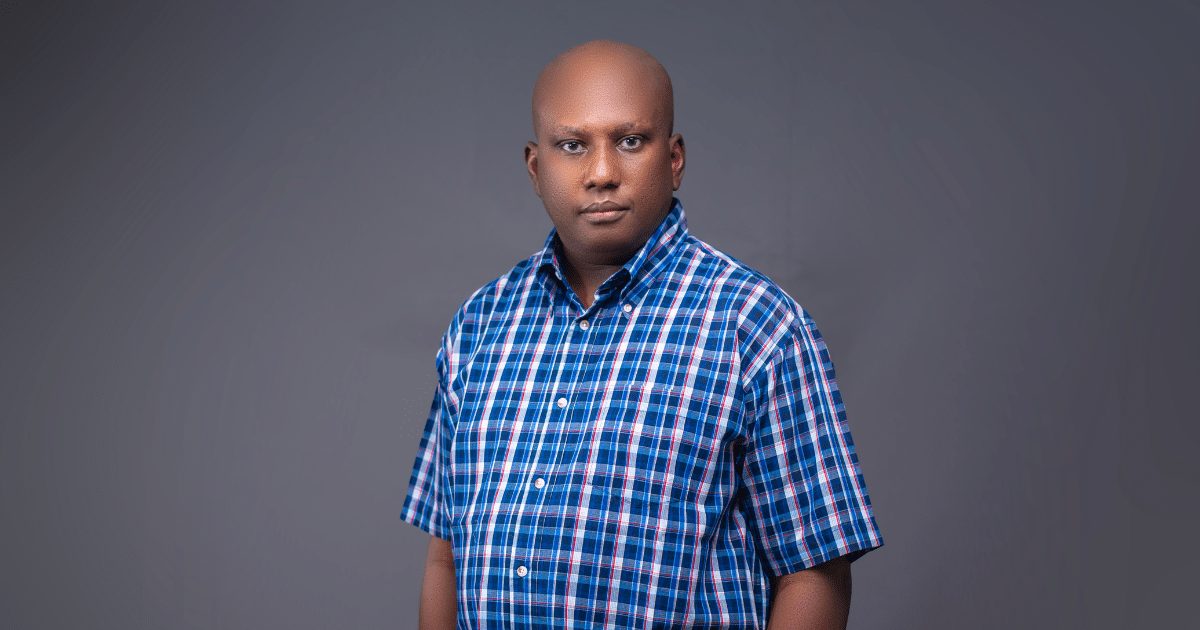

After losing a parent, Bukar Mamadu sought solace in writing poems, and by the time he discovered AI platforms, he was putting out songs without even knowing how to sing.

Today, Mamadu has put out other songs across streaming platforms through his AI artist called BukarSkywalker while juggling a full-time job as the Chief Engineer at the University of Maiduguri.

In this edition of After Hours, Mamadu shares how he went from studying Electrical Engineering to writing poems, and now managing an AI artist.

Early interactions with technology

The first time I ever interacted with technology was in 1989, at my uncle’s house in Lagos. I had just gained admission into King’s College, Lagos, and I was staying with his family for a few days before school resumed. He had a PC in his study, and my cousin and I sneaked in one afternoon to look at it.

When we turned it on, all I saw was a black screen with a blinking cursor, MS-DOS. I typed, “What is your name?” The computer replied: “Bad command or file name.” I tried again. “How old are you?” Same response. That was deeply disappointing.

From the movies I had watched growing up, I thought computers were supposed to be intelligent, conversational things. I assumed they would speak to me the way ChatGPT does now. Instead, I realised that computers are only smart if you learn how to talk to them.

By the early 1990s, I was already learning BASIC programming in secondary school. My father later brought home a Sinclair ZX Spectrum from his office at the University of Maiduguri, and although it got damaged due to voltage differences, I studied and learned the manual.

After secondary school, there was usually a gap year before getting into higher institution. So instead of waiting idly for university admission, I enrolled in a computer diploma programme.

That was in 1994, long before Microsoft Office, and so we used WordPerfect, Lotus 1-2-3, and dBase.

Victoria Fakiya – Senior Writer

Techpoint Digest

Stop struggling to find your tech career path

Discover in-demand tech skills and build a standout portfolio in this FREE 5-day email course

From there, I studied Electrical and Electronics Engineering, and later earned a PGD and an MSc in Software Engineering. Today, I work as the Chief Engineer and Head of the Computer-Based Testing (CBT) unit of the University of Maiduguri ICT Center, overseeing systems, networks, and computer-based testing.

From poetry to making music

Unlike technology, writing was never something I thought would define me. I was a science student through and through. I loved numbers, logic, and analytical thinking, and so English was one of my least favourite subjects.

That changed when my mother died in my early twenties. I needed an outlet, something to help me process grief, and writing became that outlet.

I started writing poetry, not because I wanted to be a writer, but because it was therapeutic. Initially, the poems were meant to honour my mother. Over time, the themes expanded into spirituality, purpose, and how to navigate the world. By 2000, I had compiled a manuscript, but I didn’t publish it until 2011. I felt too young to speak authoritatively about life, so I waited.

Around the same period, music began to influence my writing. I listened to everything from R&B to country, gospel, and hip-hop. That was what I consider the golden era of R&B: Boyz II Men, New Edition, and Babyface.

I became fascinated with songwriting and started writing lyrics in different styles. I wasn’t a musician, and I couldn’t play the keyboard or the guitar, but I could write, and so lyrics became an extension of my poetry.

At some point, I tried to turn my lyrics into actual songs. I reached out to musicians abroad, and one of my songs, Love Comes, was recorded in Nashville by live musicians and vocalists.

But the process was unsustainable. Recording a single song could cost $300 to $500, an enormous amount when converted to naira. Worse still, there was no guarantee of monetisation. Some studios reused beats, making it impossible to distribute songs on streaming platforms.

I realised that while I had the words, I didn’t have the resources to pursue traditional music production long-term.

Leveraging technology

Things changed when I discovered generative AI music platforms like Suno.

With AI, I could input my lyrics, define the genre and vocal style, and generate full songs, vocals, instrumentals, and soundscapes without stepping into a studio. I could iterate until I got exactly what I wanted. With a pro subscription, I also owned the commercial rights to the music.

In December 2022, I uploaded Love Comes to streaming platforms using the name BukarSkywalker, a virtual artist I created to represent my songwriting rather than my physical self.

I funded everything alongside my wife. We’re both civil servants. There were no investors because I didn’t want to lose creative control or dilute the message.

Globally, AI music is no longer experimental; it’s becoming mainstream. Virtual artists like Xania Monet and I’m Oliver, have been signed to major media companies. Xania Monet reportedly secured a $3 million deal. The Grammys have already awarded AI-assisted music, including a Beatles track recreated using AI-enhanced vocals.

Major labels like Sony, Universal, and Warner have accepted that AI is here to stay. Instead of fighting it, they’re licensing likenesses, voices, and catalogues for ethical remixing and monetisation.

For me, this validates the direction I chose. I knew early on that streaming alone wouldn’t sustain the project, so I expanded.

I made my AI-generated songs and lyrics available for licensing on platforms like Songbay. Anyone can license my work for commercial use, while I earn songwriter royalties. I also sell poetry books and maintain a Linktree hub that brings together the music, writing, licensing, and blog content.

What surprises me most is how little awareness exists around AI music in Africa. These tools already support African languages and styles. You can generate songs entirely on your phone without studio time or expensive equipment. I generated all my songs using my smartphone.

The problem isn’t access; it’s awareness and mindset. We’ve seen this before. Telecoms, fintechs, and even Afrobeats were once dismissed but are now globally accepted. Someone just has to start.

My everyday life with technology

Technology is my daily routine. I troubleshoot systems, manage networks, oversee computer-based exams, and stay deeply immersed in digital tools as a computer engineer at the university.

WhatsApp and Gmail are my most-used apps. I read newsletters constantly as well. The ones like Techpoint Digest that involve tech, finance, and startups, because learning never stops.

My biggest challenge isn’t the technology itself, but its location. I’m based in Maiduguri. There’s no real tech ecosystem here. No Scrum meetups. No Jira boards. No Slack communities.

I had to learn many tools online, reaching into Lagos-based communities like AltSchool Africa. I enrolled in 2022, and at the time, I was in my forties and probably the oldest person in my cohort.

Initially, I wondered who would even teach software engineering. But AltSchool changed my perspective completely. I saw Nigerian engineers based in Lagos who could compete with anyone globally. That experience convinced me that Africa isn’t lacking talent. What we often lack is belief, ecosystem, and infrastructure.

If I could build any tech product today, it would be an AI music generator specifically for Afro-gospel.

I would buy the domain AfroGospelAI and build a niche tool like Suno focused entirely on African gospel sounds. I would use APIs like ElevenLabs to power it.

The future of African tech

I’m bullish on Africa’s tech future. I’ve seen Nigerian engineers compete globally. I’ve watched young people from Lagos get international jobs without leaving the country.

In the next five to ten years, I believe ICT, not oil, will be Nigeria’s most valuable export. If we continue reforming, investing in skills, and embracing innovation, Africa won’t just consume technology; we’ll build it, export it, and shape its future.

And for me, BukarSkywalker is simply my way of contributing to that future.