Technology is now a part of human existence; the two can no longer be separated. In 2000, there were about 740 million mobile phone subscriptions worldwide. By 2020, that number had grown to more than eight billion, meaning there are now more phone subscriptions than people on Earth.

Today, people are more likely to connect online than in person, depending on where they live. This means that one of humanity’s defining traits, socialisation, is now heavily shaped by technology.

Interestingly, while technology determines who we talk to and how we talk to them, it is also beginning to shape what we believe and how we practise those beliefs.

Studies of urban Muslim communities, for example, demonstrate that the Internet has facilitated easier and more immediate access to worship and religious knowledge. But this accessibility comes with trade-offs — individualism in religious practice, fragmentation of interpretation, and questions around authenticity.

With artificial intelligence now in the mix, access has improved even further. But do the trade-offs increase as well?

How some churches are already using AI

Across the world, churches are beginning to experiment with artificial intelligence in surprising ways. In Finland, a Lutheran church recently hosted a service almost entirely designed by AI, from the preaching to the prayers. An avatar preacher was projected on screen, addressing the congregation like a human pastor.

The organisers said it was a test of how technology could “complement” rather than replace faith. While attendance was high, many worshippers described the experience as “cold” and “distant,” a reminder that spirituality can’t be fully automated.

In Switzerland, St. Peter’s Chapel in Lucerne unveiled what it called AI Jesus, an interactive chatbot trained on religious texts that allows visitors to “confess” and ask questions in more than 100 languages. Church officials described it as an experiment to make spirituality more accessible in a digital age, though critics called it “soulless” and even “the work of the devil.”

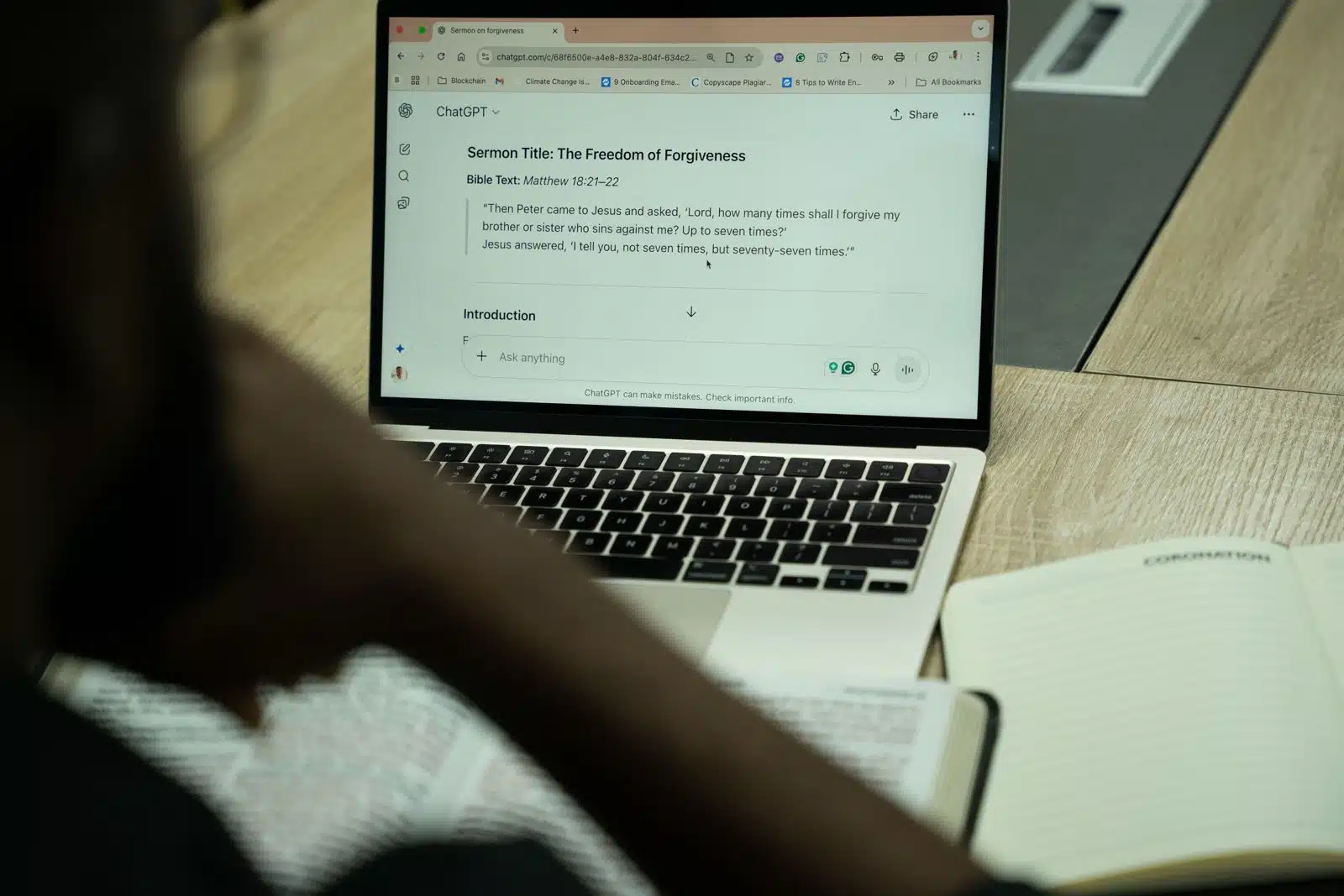

Meanwhile, in the United States, Pastor Keion Henderson of The Lighthouse Church in Houston uses ChatGPT to help with research and administrative work. “AI isn’t replacing prayer or inspiration,” he told the Houston Chronicle. “It’s helping us manage time, organise outreach, and stay efficient.”

These stories may sound futuristic, but Nigerian pastors are already finding practical ways to incorporate AI into their own ministries.

Pastor Olalekan Folarin, who leads a Lagos-based congregation, uses ChatGPT mainly for research and administrative tasks. “A good portion of sermon writing is research,” he explained.

“You’re looking at the historical and cultural context of scripture, drawing references across time and cultures. AI helps me gather all that information in one place.” He also described using AI tools to estimate church project costs, noting that the system’s figures closely matched professional estimates.

However, Folarin draws a clear line between assistance and authorship. “I don’t think a pastor should use AI to write his sermon,” he said.

“AI can help you read your sermon, refine it, or find examples, but conviction cannot be generated by a machine. If you preach without conviction, you’re lying to people.”

Pastor Ogechukwu Chijioke, founder of Circle Church Global, shares similar sentiments. For him, AI is a “research assistant,” not a spiritual substitute. He often uses it to cross-reference historical information and theological ideas, but believes true preaching must come from a place of lived faith.

“AI can give you facts,” he said, “but it can’t give you fire. It can’t make you believe what you’re saying.”

For Pastor Sunday Imole, who leads a denomination headquartered in Lagos, AI use is more limited. “I don’t have anything against it,” he said, “but since Google already integrates AI features, I might as well be using it.”

His use of technology is confined to researching historical facts that aren’t captured in the Bible.

While European churches may have taken experimentation further, pastors in Nigeria have largely confined AI to research and administration. But it raises a bigger question: has technology always been just a tool for religion, or has it quietly reshaped the very essence of spiritual experience?

Tech and religion: a match made in heaven

AI might be the hottest trend now, but technology has long played a profound role in shaping religion. One of Johannes Gutenberg’s motivations for inventing the printing press, for example, was to make the Bible more accessible.

That accessibility triggered a fundamental shift in how Christianity was understood and practised. According to Mayuri Jayesh Patil in the International Journal of Computer Applications (July 2024), “The availability of printed Bibles and religious texts instigated religious reformation movements such as the Protestant Reformation.”

With ordinary people able to read the Bible for themselves, they began to notice inconsistencies between Church practices and biblical teachings. Print technology also became a powerful tool for reformers such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli, who used it to challenge the authority of the Catholic Church. Theological disagreements soon followed, leading to the birth of new denominations.

In essence, a single technological innovation transformed Christianity from a largely authoritarian institution into one driven by individual conscience and personal interpretation.

After the printing press came radio and television. Suddenly, a pastor could be present in people’s homes, turning mass media into a powerful tool for evangelism. The rise of modern transportation further accelerated missionary work, making it easier and faster to reach wider audiences.

Looking through history, it wouldn’t be out of place to say that technology has often been one of religion’s greatest allies.

However, not everyone shared that optimism.

Each new wave of innovation has raised ethical concerns about its effect on faith. In the age of the printing press, critics feared that mass-producing the Bible would encourage inaccurate interpretations. According to an article by Spiritual Culture, extremists and political actors also exploited the press to spread propaganda disguised in biblical language, blurring the line between truth and error.

The story hasn’t changed much. Every technological leap brings both progress and peril.

For instance, while livestreaming platforms allow people to attend services from anywhere in the world, a paper titled The Collision of Technology on Religion: An Overarching Complete Analysis argues that these same innovations can lead to distraction, diminish the authenticity of worship, and promote superficial engagement.

The scary thing about AI in religion

In many ways, AI isn’t that different from the printing press. Instead of flipping through pages, you can now enter a prompt and instantly learn anything. That’s a good thing — a simpler way to access the Bible and related literature.

Pastor Ogechukwu Chijioke even argues that AI isn’t just a useful research tool for pastors, but also for church members.

“Research is important for both pastors and members,” he said, “especially when it comes to sermons that are more expository in nature.

For instance, we’re doing a teaching series on culture, and part of that is exposing modern culture and juxtaposing it with history. A lot of that requires research, and ChatGPT does a very beautiful thing.”

ChatGPT also does “beautiful things” for Pastor Olalekan Folarin, particularly when he’s working on what he calls sticky topics.

“You need to ensure that your message sticks,” he said. For him, using AI is a bit like using a tool to craft a catchy headline after writing an article — something people can easily understand and remember. He also uses AI for creative projects, such as turning sermons into articles or even books.

Pastor Sunday Imole, who doesn’t intentionally use AI, agrees that it can serve as a valuable source of information. Still, he warns against specific use cases that could have “scary outcomes” if not handled with caution.

AI vs the Holy Spirit

On one thing, all three pastors agree: there’s a serious problem when AI begins to do what the Holy Spirit is meant to do.

To them, sermons aren’t just about delivering information; their essence goes far beyond that. As Chijioke put it, “It’s not just based on the veracity or truthfulness of the message; there’s a conviction element in the sermon. AI cannot reproduce conviction.”

Imole takes it a step further. For him, the issue isn’t limited to sermon preparation — even fact-checking your pastor with AI could be spiritually dangerous. He believes members miss out on vital experiences when they avoid the hard work of seeking understanding for themselves.

“AI can easily tell you if something is right or wrong,” he said, “but there’s a process of metamorphosis that the member is missing out on. It’s like math; when you remove the workings, you deprive the student of the process of understanding.”

He referenced 2 Timothy 2:15, which encourages believers to study the Bible diligently. “With AI, you miss out on the labour of reading the verses, meditating on them, and reflecting on the points made by the pastor,” he added.

In a way, the same concerns raised when the printing press was invented still hold true for AI. While access to information has become easier, the discipline required to study, reflect, and build conviction risks being lost.

In the end, the pastors conclude that technology itself is neither good nor bad — its impact depends entirely on how it’s used.

However, if these tools are used the wrong way by more and more people, they could dilute the very essence of a religion.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.

(*) Not real name