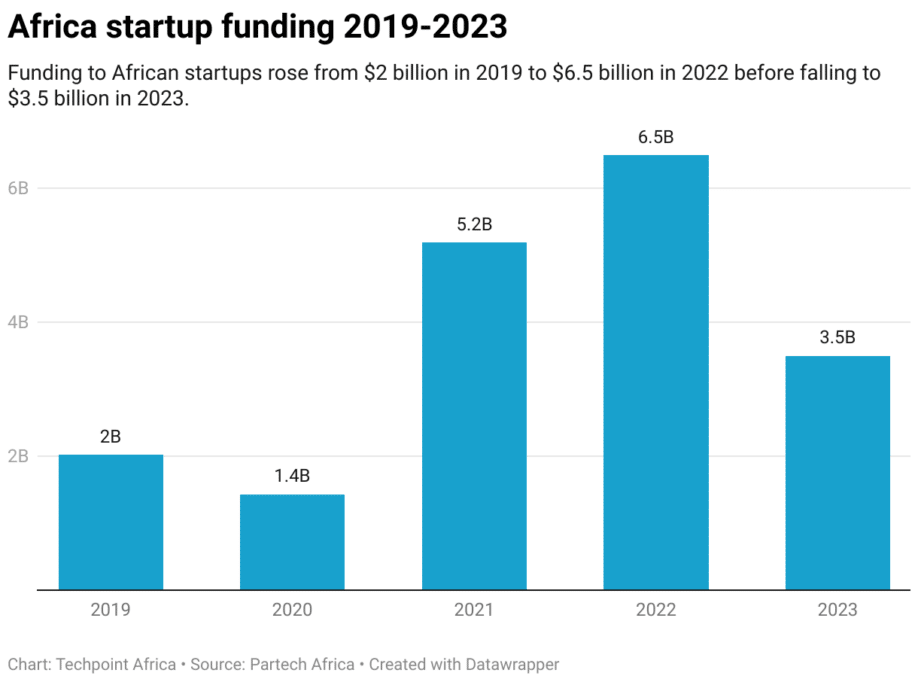

Between 2019 and 2021, interest in African startups soared, with venture capital investments rising from $1.3 billion in 2019 to $4 billion in 2021.

Fuelled by a zero-interest rate policy in many parts of the Western world, investors rushed to invest in African startups with hopes of making huge returns.

By 2022, the craze was wearing off as many investors got more circumspect when evaluating potential investments. With only $2.27 billion raised in 2023, Africa’s funding environment is returning to pre-2016 levels, according to Eghosa Omoigui, Managing Partner at EchoVC.

Fundraising is tough for founders and investors

With individuals and investors flush with cash, the standards for raising venture capital fell, and many startups that would not have otherwise raised venture capital did.

That has caused a shift in startup and venture capital circles. While startups now have a harder time raising, investors also report similar difficulties when raising from limited partners.

For fund managers who raised their first funds during the boom years of venture capital, LPs are now requesting some proof that they can return a fund. Even more experienced fund managers are having a tough time convincing LPs to choose venture capital as an asset class as other investment vehicles promise guaranteed returns.

“It’s getting very hard, and LPs are now asking for what is known as DPI, which is actual distributions. In other words, have you actually been able to exit some of these companies and distribute cash? That’s really hard.”

Angel investors have also made fewer investments, according to Joe Kinvi, Co-founder of investment syndicate, HoaQ.

Most syndicates, he says, invest alongside venture capital firms, as their cheque sizes are often too small to meet a startup’s capital requirements. But with VC firms making fewer investments, angels are also scaling back.

Rising interest rates also mean these angels are less likely to take a risk investing in startups when they could have guaranteed returns in other asset classes.

Data from PitchBook shows that fund closes are taking longer than previous years, with 37% of first-time US VCs not expected to raise a second fund.

On average, closing a fund now takes up to 15 months, up from nine months in 2021 and many venture firms are raising funds below their initial targets.

Fundraising difficulties are a blessing in disguise

Despite these challenges, Bernard Ghartey, Investment Manager at Norrsken22, believes there are some positives to the situation.

“Frankly, there were some business models that raised VC cash that shouldn’t have. Unfortunately, the implication is that some of these companies will not be able to raise follow-on funding and will eventually shut down.

“Ultimately, the standards being high is a good thing for the ecosystem, so that strong founders with strong business models built on strong unit economics and strong fundamentals are those that will have access to capital.”

The funding situation has forced many VCs to adjust their positions. Where startups were previously encouraged to pursue growth, more emphasis is now being placed on profitability.

“When you’re profitable, funds want to give you money because you’ve de-risked yourself significantly, they want to be able to fuel your growth, and they can see that the unit economics are working,” Kinvi said.

On his part, Omoigui explains that the current focus on profitability is not a silver bullet. While VCs may be encouraging startups to push for profitability, he points out that it does not necessarily guarantee interest from VCs.

In addition to pushing startups towards profitability, Kinvi adds that investors now encourage portfolio companies to start fundraising before they need to.

“I think the best companies should be raising money when they don’t need to raise money. When you go out to the market and you look desperate, nobody wants to touch you because the risk is just too high. If they’re going to give you capital, they’re going to spend months doing due diligence, and that process can kill you as a startup,” he explained.

Investors are also placing more stock in a founder’s ability to build a business in a tough environment. With more negative stories coming out of the ecosystem in the last year, founders are now being scrutinised more closely.

Founders and investors must make a case for their existence

While the fundraising environment can be blamed for some of the challenges faced by startups, Omoigui points out that the macroeconomic environment in many parts of Africa presents a significant challenge for startups.

Nigeria, Kenya, and Egypt have three of the largest startup ecosystems on the continent, but all three have seen significant currency devaluations and rising inflation in the last year. Consequently, startups that do not operate in key sectors or possess significant market share have struggled.

Omoigui points out that the current state of funding means that both fund managers and startup founders need to make a case for their existence.

“If you don’t exist tomorrow, do your customers go into total panic? If you don’t have that, then you really don’t have product-market fit. You might have some version of it, but you don’t have the high-quality version of it,” he argued.

While Kinvi does not expect the fundraising process to get easier for all parties, he argues that founders and investors need to start pushing for exits.

Paystack’s sale to Stripe in 2020 was seen as a watershed moment for the African startup ecosystem and may have even fueled the funding growth that followed.

However, similar exits have been scarce. While there have been a number of exits in the years since then, their value has remained hidden, with some speculating that the returns were insignificant, hence the silence on their value.

“It’s unfortunate that there’s only a handful of clean exit stories you can point to when you talk about the African success story. It does not help if we are always pointing to the Paystack acquisition. We need an abundance of exit stories like this so that we can show that the VC asset class in Africa has come of age,” Ghartey argued.