On a cool Tuesday afternoon in April 2011 in Abuja, Nigeria’s political and administrative capital, lawmakers of the upper chamber gathered in their usual outfits, typifying the country’s rich cultural diversity.

At such regular meetings, lawmakers try to chart a course for Africa’s largest nation. Rounds and rounds of endless debates are usually adjourned till another day when the cycle continues. But April 24, 2011, was different. The lawmakers had reached an era-defining decision.

Among other deliberations for that day, the National Assembly passed the Freedom of Information Act (FOI Act) after years of contemplation. Four days later, the then-president, Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, assented to the bill, unlike former President, Olusegun Obasanjo who refused to pass it into law when it was first proposed in 1999.

This move came with a lot of commendation, especially from the press — the Fourth Estate of the Realm — as it’s expected to promote press freedom, improve the citizens’ general well-being, and develop democracy, as seen in Western climes.

Curious about the reason for the excitement?

Simply put, the purpose of the Act is to make public records and information more readily available. That means custodians are compelled by law to provide public access to public records and information on request. It even goes as far as protecting serving public officers from adverse consequences of disclosing certain kinds of official information without authorisation.

Is your local government working on a street light project in several towns and villages? You have a right to know the budget and contractors and even demand an explanation for any delays. What about how much the government collected in tax and how it was spent?

The underlying philosophy of FOI is that the population has the right to know what public servants, who are custodians of public trust, do.

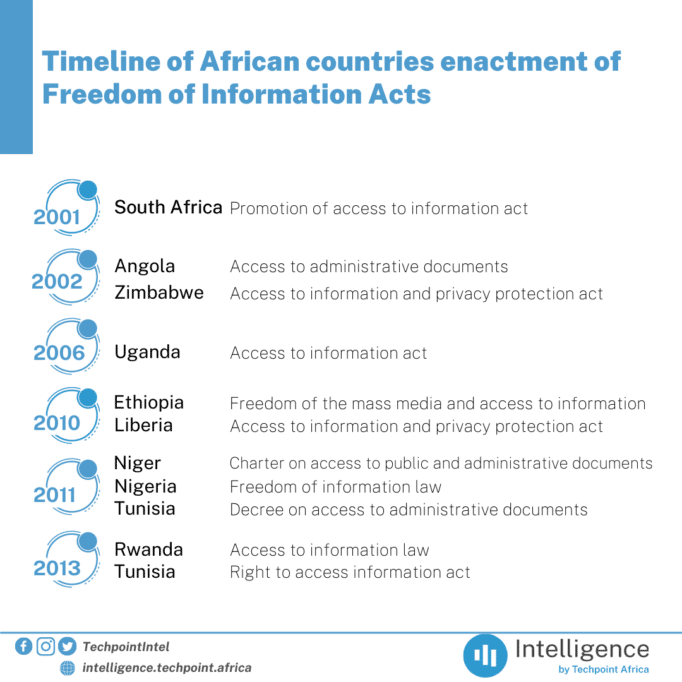

Interestingly, Nigeria is one of 11 countries with an FOI Act out of Africa’s 54 nations. South Africa was the first to enact a Promotion of Access to Information Act in 2001.

Even International bodies like the United Nations (UN) and the African Union (AU) often encourage an enabling environment to enact FOI laws while fostering active use by supporting social awareness.

Ideally, this should mean that the continent is gradually embracing the freedom of information.

However, what’s the situation two decades on? A cursory look will show intermittent attempts to shut down free speech in these countries, coming via irregular unfair legislations and vetos.

Recognising or adopting the right to information might not be enough, and despite the efforts of international bodies, most governments only seem to pay lip service to these laws.

In 2020, nearly a decade after Nigeria passed its law, a Premium Times and UDEME investigation revealed that 16 Nigerian states were yet to establish processes to promote transparency in government.

This was confirmed after submitting 162 FOI requests across Nigeria’s 36 states. Of 600 requests in 2 years, only 30% of the recipients treated their requests and disclosed information; the others either ignored the requests or provided no information after acknowledging them.

This means that public officials who violate these laws are obstacles to press freedom as they monopolise the power to make information public.

Violating the FOI Act

According to the United Nations (UN), FOI is an integral part of the fundamental right of freedom of expression, which covers the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers.

Per the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), infringement on this right includes, but is not limited to, violating press freedom and freedom of expression on the Internet.

On the latter, ‘Internet’ covers every other type of emerging media as long as it contributes to development, democracy, and dialogue.

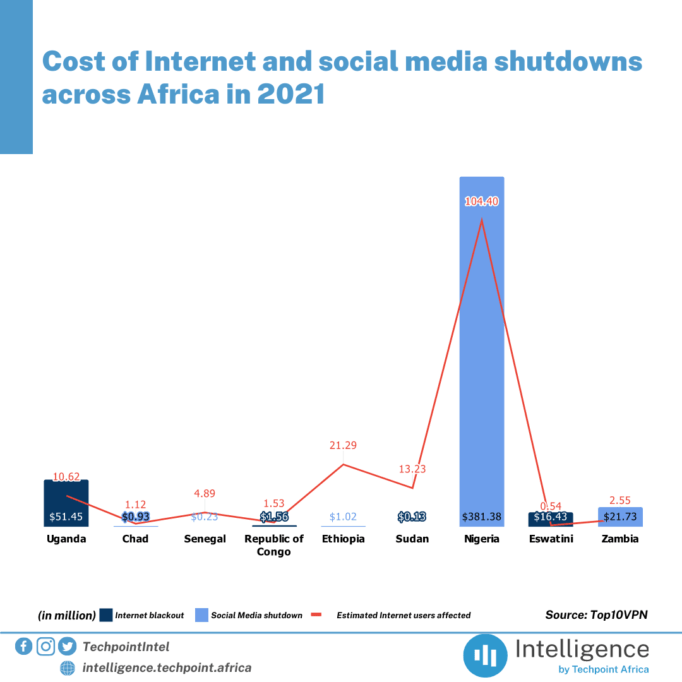

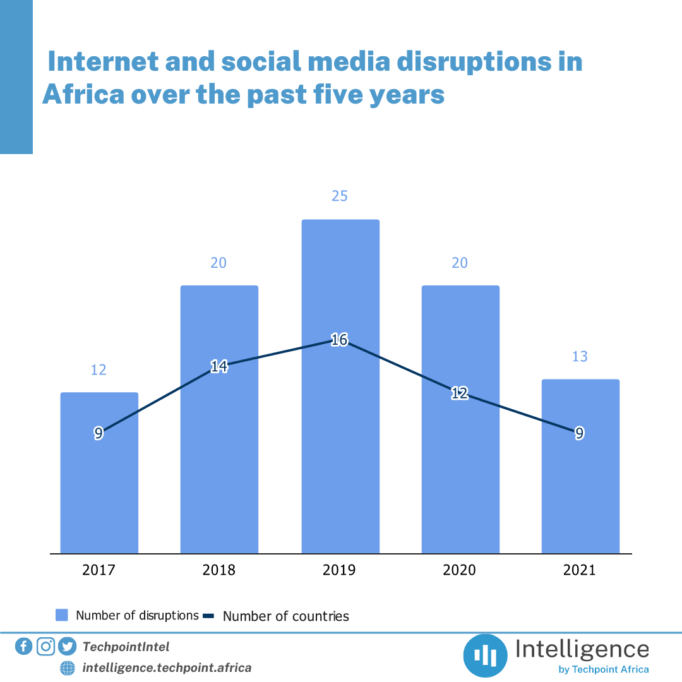

Ironically, Africa lost approximately $454 million and 2,802 hours between January and August 2021 to several forms of government-imposed social media shutdowns and Internet blackouts.

Factoring in Nigeria’s ongoing Twitter ban, over 160 million Internet users have been affected, with Uganda, Chad, Senegal, Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Sudan contributing to the total figure.

Interestingly, the bitter opposition to the Social Media Bill and Digital taxes in Africa has failed to halt proceedings.

The ordinary social media user and online tools adopters in Lesotho, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Togo, Tanzania, and Nigeria face hard times because of issues around regulations.

Nigeria’s ongoing Twitter ban isn’t good for a country whose Digital Rights Bill is in limbo.

The government is aware that with a Social Media Bill successfully passed, moves against Internet use, for instance, become less controversial. And this also applies to digital taxes.

Interestingly, policy research firm, Tech Hive Advisory, released a report in August 2021 which revealed that four countries — Nigeria, Ethiopia, Botswana, and Kenya — have laws ensuring freedom of expression and privacy for their citizens, as well as laws that violate them.

Samuel Ibemere, Editor-in-Chief, Ripples Nigeria, confirms to Techpoint Africa that one viable trap of the government against press freedom is legislation.

The government looks for remotely applicable rules and proposes an amendment that promotes the agenda of censorship. And when this doesn’t work, they act outside the law, circumventing it in the process.

Controversial reasons

We gathered that most of these shutdowns result from elections, protests, conflicts, information control, and national examination.

But in reality, it goes beyond that.

Data protection expert, CEO and Co-founder of Tech Hive Advisory, Ridwan Oloyede, explains to Techpoint Africa that information hoarding mostly occurs because of intolerance to accountability and transparency.

Drawing upon his 35 years of experience in different capacities, veteran journalist Lekan Otufodunrin agrees and opines that in trying to evade the oath of office that they swore to uphold, they try to dictate what the media should report.

Having a platform to hold public office holders accountable and instruments to demand more from them might be the highest power ever handed to citizens. And incidentally, this is what is expected from democratic governments.

From a psychological perspective, putting the populace or the media in a situation they have no control over renders them helpless, which is what holders of public office seek to achieve.

As revealed by Dr Catherine Oyetunji-Alemede, a social psychologist, “When people don’t have access to information, they tend not to know what to do.”

She further adds that “not knowing what to do takes you to a psychological state of learned helplessness.”

Learned helplessness conditions people to see bad situations as inescapable and unchangeable, such that it is passed down to the next generations. This is achieved by consistently portraying that a state of social helplessness is normal. This does not bode well for a country practising democracy.

Everyone can be a watchdog

Over the years and across different geographies, the media has served as watchdogs of the government and the ‘powers that be’ in society. For this reason, the media is regarded as the fourth estate of the realm, behind the Executive, Legislative, and Judiciary.

Members of the press typically go above and beyond the call of duty, defying threats, risking bodily harm, and working with limited information.

Consequently, no one can fault them for expecting positive change following the enactment of FOI laws. And in the digital age, the conversation is gradually changing.

Temitope Olaiya Templer, News Editor, The Guardian Newspaper, says information hoarding has always been a major challenge for journalists, but the coping strategy has evolved with the times.

“I think this trend began when they saw the power of citizen media. Before now, it was easy to control broadcasts and prints, but online has been difficult to manage. And the more citizen journalists get on social media, the harder it is for the government to react.”

Per Ibemere, in the past, when print and broadcast houses were shut down, journalists had to go underground to keep distributing the news.

“Today, the government realises that the means of distribution is rapidly expanding beyond its control with the use of social media. So it’s no surprise to see them try to shut down this new means of distribution. But for how long can the government continue this?”

In the heat of the Twitter ban in June, Gbenga Sesan, Executive Director of Paradigm Initiative, who shares similar sentiments, said that with more of the government’s plan to retain and expand control comes more pushback from the populace as they become more exposed and enlightened.

Citizen journalism encourages the ‘see something, say something’ culture, which has been used for election reporting. But surprisingly, the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC) of Nigeria reportedly fined three media firms not less than ₦2 million ($5,263.1*) for reporting the October 20 #LekkiMasaccre using eyewitness reports

The NBC recently announced plans to license OTTs, but that wasn’t the government’s first attempt. NCC’s similar moves in 2016 and 2019 were abandoned following opposition, and Sesan explained why this latest attempt would fall through.

“What the government hasn’t done is to publish the details of the licence. But they can’t because there’s no licence like that. OTTs are not broadcasters; they are platforms, even though people use them for broadcasting. There’s a reason they are called intermediaries.”

Undoing the muzzles

“Being deprived of information is close to some form of intellectual slavery. Also, being unable to access credible, fact-checked, and timely information in the time of emergency could be the difference between life and death,” Oloyede says, stating why the media can’t afford to be laid back in the face of information deprivation.

However, the press can’t be silenced.

Otufodunrin, who is now the Executive Director of the Media Career Development Network (MCDN), discloses that before and during his time as the managing editor of The Nation Newspaper, he witnessed various forms of censorship but learnt how to cope while doing everything to reverse the situation.

“Before the emergence of new media, there were traditional ways of practising journalism which are still reliable in going about our editorial work. The censorship can only limit our operations but can’t totally stop us from doing our work,” he tells Techpoint Africa.

Olaiya sheds more light on this, saying that it’s difficult but left to choose between going ahead with incomplete information because concerned authorities are not forthcoming or using anonymous third parties or persons of interest willing to compromise, journalists will pick the latter.

From recent experiences, he establishes that using the FOI laws as an instrument to compel a response to requests isn’t always as effective as it should be.

With this instrument becoming less effective, Oloyede maintains that there’s more to be done.

“Beyond having a law in place, it’s important to also put in place mechanisms to ensure that the laws do what they’re meant to do. Like judges being trained on how they work. Government agencies or private organisations and businesses enjoying collaboration with the public authority have the capability to provide information to people when they request it.”

In such situations, Olaiya often tells his team to “stay with the facts” while discarding emotions.

“When you stay with the facts, no matter the harassment, the trolling on social media, callout by government agents, and paid social media influencers, the facts will always speak,” he adds.

Ibemere also alludes to instances where social media influencers and random people come to bash fact-driven investigative stories. Still, he points out neither the press nor the citizens should be forced into a situation where they can’t hold the government accountable.

Oyetunji-Alamede highlights what this implies.

From a decade of practice as a social psychologist in academia, she submits that the tendency for citizens to resort to revolution, anarchy, or extreme chaos increases with prolonged infringement on the right to information. Circumventing this sometimes makes people search for a less restrictive environment outside the country.

This brings to mind a radical investigative journalist, David Hundeyin, working from outside the country’s shores.

Playing in the media space is dicey in Africa.

On the one hand, journalists must be very professional in their duties and abide by the profession’s best practices. But on the other hand, sometimes they either make exemptions or do nothing.

According to Olaiya, there’s usually a negative outcome when a government consistently refers to select media outfits as purveyors of fake news because they present the facts they have in the face of insufficient information resulting from the withholding of pertinent details.

This threatens to weaken journalistic integrity and the authenticity of media reports. And if sustained, the media outfit loses its credibility per time.

Since there are always two sides to a coin, some outfits play it safe and release teasers with the promise of more details to come. That this is bad for their image is a no-brainer.

However, Ibemere says that the media still needs its independence to feed the populace with fact-checked information, which can be achieved notwithstanding current challenges.

In his opinion, “What the media can do to overcome those obstructions is to also play within that legal space. We need to be able to identify what those obstructions are. We query those legislations.

“The media is not irresponsible. We want to ensure that we live by the rules, and we’re also aware that some of those rules have been deliberately instituted so that we don’t enjoy any breathing space.”

International Day of Universal Access to Information

As stated by the UN, the world recognises the significance of access to information on September 28, the International Day of Universal Access to Information.

This year’s theme is “The Right to Know – Building Back Better with Access to Information.”

Unfortunately, many African countries rank low on the World Press Freedom Index as far as their activities in 2021 are considered.

Ethiopia, for instance, ranks 101st, with Kenya just one place behind in the 102nd position. Nigeria sits in the 120th spot and Zimbabwe ten further in 130th.

This is despite these nations having existing FOI laws that should ordinarily entrench press freedom and the freedom of information.

Beyond days like this, people living in Africa and the press are reminded to be bold enough to oppose guerilla legislations that violate their rights to timely and credible information.

Ultimately, Gbenga’s parting words should ring loud: citizens shouldn’t feel intimidated in the face of opposition. This is a democracy, and boldness is needed to push plans that will impact them positively.