Kiishu* was still running her undergraduate course when she decided to explore other parts of the country for her six-month internship program. Miles away from home in South-southern Nigeria, she was having an enjoyable learning experience, but with two months to go, she had an awful experience.

She was sexually assaulted by her host’s friend, who visited, knowing his friend was away on a trip.

“It was a cold and sad evening,” she recounts, “but help came, albeit late.”

A trip to the police station provided no succour, even though they knew the culprit. She would eventually be bullied by the perpetrator’s influential family to agree to arbitration outside court — presided over by her workplace’s governing authority — with the culprit having only to sign an undertaking to stay away from her after admitting to the crime.

“It was hard, but I agreed to take it because I had a short time to spend there.”

“Besides, neither my sponsors nor I could think of any other channel to get help.”

That was in 2014.

It’s 2021, but unfortunately, varying degrees of sexual offences are still perpetrated daily, with statistics confirming an increased incidence of the global crime. The United Nations (UN) affirms that the COVID-19-induced lockdowns in 2020 exposed vulnerable people to more risk of sexual violence.

Despite the Nigerian Federal Government launching its first sexual offender register in November 2019, there were so many cases of sexual violence in 2020. Consequently, all 36 state governors declared a state of emergency on rape, agreed to set up a sex offender register, and sign laws to punish the crime.

In May 2021, Lagos State — one of the few with an active online sex offender register — disclosed that it added 206 names to its list of sexual offenders between 2020 and 2021.

Highlighting existing response channels

Just like Kiishu, most sexual assault survivors don’t bother to report their experiences. Their overriding emotion is often fear that their complaints won’t get the required attention, and they’d either be blamed or stigmatised. There is also the possibility that the perpetrator would not be brought to book, further putting them in harm’s way.

However, the number of channels currently available to report such cases have increased compared to recent years. Victim support groups, activist movements, non-profit establishments, government-owned humanitarian agencies, and global organisations like the UN are just a few of the options available to victims.

“A friend introduced me to this support group that helped me talk about my experience. Even though it was years after the incident, I experienced closure and felt I could properly get justice if I wanted to,” Kiishu relays.

Apart from support groups, there is the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP), a government-owned organisation that monitors trafficking and sexual-based violence cases.

Interestingly, they have multiple channels — one of which I tried during my investigation — for receiving and addressing complaints.

I called the conspicuously written toll-free number on the NAPTIP website and got through to a representative in less than 60 seconds; receiving a response redirecting me to the office closest to me took less than 120 seconds. While the response time was quick, I have no idea how long it would have taken to dispatch help to my location had I been in danger.

The Agency’s impressive setup is the result of deliberate work done over time.

Mr Ganiu Aganran, NAPTIP Zonal Commander for Lagos State, who leads the Sexual and Gender-based Violence unit, tells Techpoint Africa that different tech-enabled channels have made it easier to access help.

“At the headquarters, we have a 24-hour monitoring centre. When a call is put through, whatever is said is recorded and sent to the appropriate command that will handle it in real-time. We also receive SOS through the website and emails.”

Though he cannot speak to the number of reported cases and prosecuted offenders, he says that “in the Lagos Zonal Command, sometimes, in a week, we have nothing less than 35 cases coming in, including those that come from sister law enforcement agencies through referrals.”

Aganran says that social media has been a great tool, and with action taken to address the many cases reported on social platforms, his claim appears to be true.

Between March and June 2020, several campaigns aimed at getting justice for rape victims trended on social media.

However, Aganran submits that the same channel is also responsible for the increasing cases of sexual violence and human trafficking.

He admits that the Agency would have been able to do more if it has more tools to work with. There are limitations apart from funding,

“The issue of tracking could come in, but we do tracking through our partners, especially the DSS or the police. These are some of the law enforcement agencies that have this technology, which may not be available when we have to check the environment well to respond promptly.”

However, with relevant partnerships, he concludes that the agency can cover more ground.

More hands at work

Aganran attests that the Agency usually looks to partner with private organisations — for public awareness campaigns, information gathering, and referrals, among others — so it does not get overwhelmed.

“We can never have it enough; there are challenges. The issue of logistics is key. You need to be able to move your victims when you rescue them. There are other things like going to court, going to arrest, and going for surveillance; all these demand a lot. But the truth is that working closely with partners, they also come to our aid.”

Apart from NAPTIP partners, there are platforms operating in Nigeria that do the same thing.

What survivors want: Enter WARIF…

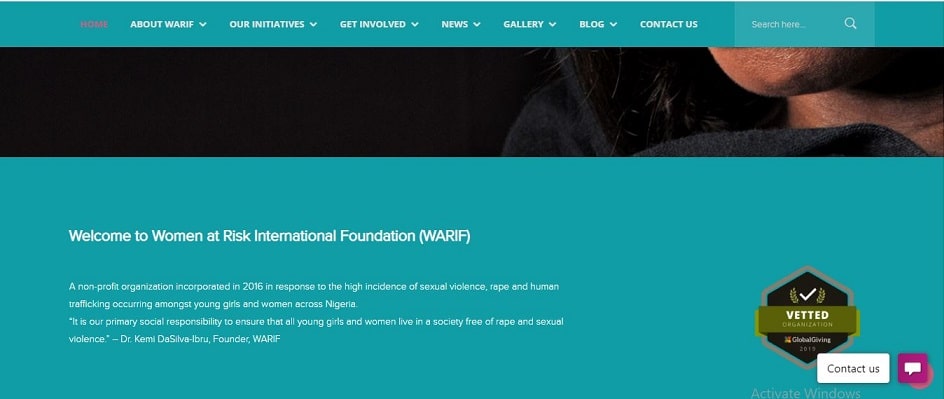

For obvious reasons, what a survivor wants is to be heard, cared for, and defended. The Women at Risk International Foundation (WARIF) is a non-profit organisation launched in 2016 to respond to and care for young girls and women who are victims of rape.

The Foundation’s website serves as a channel for anonymous reporting, legal and health assistance, and evidence gathering for the police. It also has a feature that allows survivors to have virtual group therapy.

During the lockdown in 2020, it improved the platform’s live chat feature and looked for cases on social media.

Government-owned agencies also refer cases to WARIF’s rape crisis centre. And Kemi DaSilva-Ibru, WARIF Founder, disclosed that the centre received up to 300 cases between March and April 2020 in Lagos State.

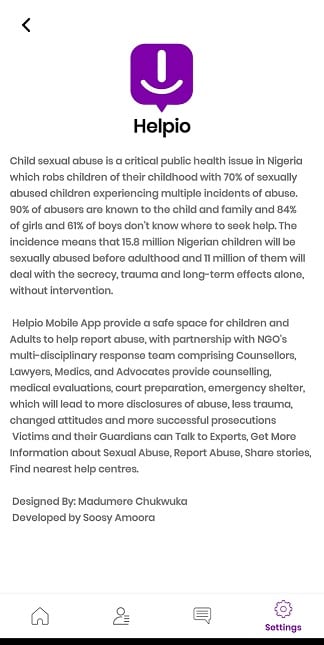

… and Helpio app

In August 2020, Kano-based Android developer and women-in-tech advocate, Sa’adat Aliyu, launched Helpio app, a platform for reporting sexual abuse cases in Nigeria.

Available in both Hausa and English languages, users can sign up either as an emergency help centre, report anonymously, share a story, render legal assistance, or provide counselling.

Aliyu informs Techpoint Africa that she was inspired to build the platform during the lockdown to remove the hindrances to reporting cases of sexual and gender-based violence and get survivors closer to help.

She believes that many rape cases are unreported because of the associated stigma. History also plays a part as there are fewer cases of victims getting justice than perpetrators going scot-free.

This can be put down either to inadequate legal representation or poverty. However, there are non-governmental organisations set up solely to fight against SGBV, which provide financial, legal, medical, or even socio-psychological support to victims of sexual abuse.

Within the first ten months of launch, the platform already has support groups and certified organisations — for confidentiality — signed up to help with reported cases and emergency calls. And for cases requiring counselling, there are experts available for live chats.

Still in its early stage, Aliyu says the platform undergoes regular changes to improve user experience. Subsequently, the platform will reflect real-time statistics of cases and include more localised languages.

She hopes to get more people to use the platform and render more help.

“Through the app, over 50+ cases were reported, and the “talk to experts” feature was among the most-used in the application.”

Aganran explains that having recognised their reach, the government wants to take advantage of the opportunities created by platforms like WARIF and Helpio.

With more tech tools in place, there’s no telling how many cases will be reported, and perpetrators brought to book.

Aganran believes that doing nothing isn’t an option as everyone must intervene, show support, or help survivors get what they want — a good reason to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict every June 19.

* – Not real name