Technology is a game-changer in many fields; even in sectors where adoption is low, it is used for a few processes to increase efficiency and productivity.

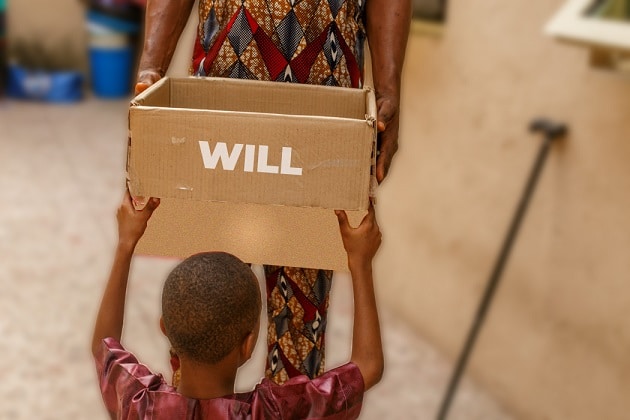

In the early days of GIG Mobility, bus ticketing was done physically at loading parks. But with its evolution in 2015, the transport company introduced call bookings, online ticketing and check-ins. And a couple of years down the line, it has become a household name in logistics and eCommerce.

Unlike in the mobility and logistics sector, tech adoption in the legal space has been relatively slow.

From my conversation with a few lawyers, two factors are responsible for this snail-paced growth: the level of paperwork involved in such legal processes, and the disparity between law and tech; while one is set in stone, flexibility is the other’s selling point.

This is probably why automation is more straightforward in some fields like logistics and mobility, health, and finance, and more difficult in others like will making, for instance.

Although new technologies simplify processes, making them more efficient and cost-effective, the challenge with adoption sometimes lies with the transition from the traditional to the automated.

Automating will and estate planning has so far been reduced to using some software and sealed written notes. Yet a fundamental problem exists.

A small addressable market

How do you begin to solve a problem that people are not willing to come to terms with? This is a question that legaltech founders, who have considered will making as a service, have answered at some point. Needless to say, legaltech is in its infancy.

Will making is similar to insurance, where people seldom consider protecting themselves against loss. For concerned companies, that’s counter-intuitive.

The barriers to will making across climes are the same with people either reluctant to write a will or even acknowledge their mortality. While some believe they have nothing to pass on, others see will making as the exclusive reserve of ageing people.

Strong cultural and religious biases further complicate the African situation.

Enyioma Madubuike, Lead Partner at Lawrathon, a legaltech startup, believes that people who are not open to the idea of writing a will are unlikely to do so online.

He calls it creating a niche within a niche.

“This makes it very unattractive for any entrepreneur to venture into because the market is very small and defining that market is going to cost you a lot,” Madubuike submits.

From the look of things, some entrepreneurs are willing to bravely set sail on the stormy waters of will and estate planning despite apathy among people.

In 2018, two lawyers co-founded a digital will and estate planning platform, Carrot, arguably the first of its kind in Nigeria. And Odunayo Williams, Carrot CEO, hated their experiences during the startup’s early years.

“Culturally, will writing is not a Nigerian thing. They see it as a prelude to death. Religiously, people have a negative attitude towards it. The toughest years were at inception; we had to do a lot of awareness, and we still have a long way to go.”

For Williams, the challenge is not that of not finding a market fit for Carrot. He believes that getting people to protect their immediate families ahead of their demise is worth the effort.

“We are tackling this by having conversations with groups and organisations that hold monthly meetings. We also encourage young people to write their will as a way of measuring their growth over a period of time.”

People need to acknowledge a problem before automation is introduced to address it. And that is why the first step is demystifying the subject, a step Carrot has actively taken.

Rather than full-blown tech, a hybrid solution will suffice

Depending on the assets, will and estate planning can be simple or complex. Clarifying that a lawyer is not always needed to write a will, Williams says that anyone can write one and append a signature, thus making it legally binding.

However, the technicalities come up when the concerned individual—called the testator—wants to ensure that the will is foolproof. At this point, a legal advisor, witness(es), an executor, a guardian, and/or the probate registry must be involved.

By the way, there are boxes to be ticked when making a will:

- The testator must be in the right frame of mind

- The will must be written and signed without coercion

- Only self-owned assets can be willed

- A will should be co-signed by a witness with nothing to gain from the process

Expressing scepticism about achieving these online, Madubuike raises some questions.

How will the estate planning or legaltech company confirm all these requirements? If a will that is done traditionally can be contested on some grounds, aren’t those done online—involving forms and electronic signatures—more likely to be disputed?

Williams explains how confirming asset ownership is not the responsibility of the lawyer or the company.

“A will is received in good faith,” he says, before explaining how Carrot carries out these processes without physical meetings.

A client visits the website and fills a form by answering some questions, goes ahead to view a sample of the automatically generated will, and confirms the information provided before submitting it and making a payment.

Carrot charges ₦35,000 ($88.8) per will, an amount Williams considers little compared to traditional fees.

Back at Carrot, a lawyer prints and reviews the submission to ensure that it meets all obligations and flouts no rule. Where necessary, the client is called and the legal implications of any changes being made are explained.

After this, in partnership with DHL, Carrot sends the will to the client and waits for the signatures of the testator and witness(es). When signed, the client goes back to the website to request a pickup.

On receiving the signed documents, a lawyer prints and binds the will before taking a copy to the Probate Registrar for safe keeping. The testator also receives a copy on request.

Apparently, the whole process is not fully automated. Explaining why they have to engage some manual processes, Williams says that because the law is conservative there are limitations to the online process. According to him, the law has a lot of processes, but tech involves getting things done fast, so there has to be a balance between the two.

Addressing the concerns

Since launch in 2018, Carrot could only boast of an encouraging patronage in 2020 when, according to Williams, it recorded a 10% growth.

Perhaps, the number of pandemic-induced deaths saw people review their responsibilities to their immediate family and consider estate planning. However, Williams infers that more people now work with multinationals remotely, and these companies encourage their employees to have insurance and a will.

But before this period, the startup did a lot of marketing campaigns, put educational content on their blog, and intentionally targeted some social media posts. Williams touted its competitive pricing as an edge, stating that it currently thrives on referrals and writing proposals to companies.

Madubuike reckons that an insurance company, with an existing database for instance, can solve the challenge of a small addressable market by including will making as a service.

However, our findings show that many insurtech startups do not include wills in their list of services.

For instance, it will be easier for an automobile insurance company to add the question of “who gets this car at your demise?”

If full automation is the goal, he suggests that blockchain technology is the way to go, particularly smart contract products. Nevertheless, restrictions could come in the form of regulation.

William recommends that the probate registry should automate storing wills to forestall cases of missing wills.

Beyond seeking speedy tech adoption in sectors like legaltech and insurtech, more attention needs to be paid to building an addressable market first. To this end, Madubuike and Williams believe it is something that can happen soon.