Every country’s preparedness for artificial intelligence (AI) can be divided into five categories: power players, traditional champions, rising stars, waking up, and nascent. More than 80% of countries in Africa are so far behind that they do not fall into any of these categories.

According to the Global AI Index, Egypt, Nigeria, and Kenya are categorised as nascent, while Morocco, South Africa, and Tunisia are considered to be waking up.

If it is any consolation, only two countries — the US and China — are classified as power players. From innovation to investment and implementation, these two nations are the primary drivers shaping the course of AI.

Far behind in AI development and funding, some African countries, including Rwanda and Ghana, have created AI strategies, while others have expressed interest in developing frameworks that may evolve into policies.

Policies are not only important for harnessing the power of AI; they are also crucial because AI poses significant risks.

“We, as the producers of this technology, have a duty to be honest about what’s coming,” said Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei in May 2025. “I don’t think anyone is considering how administrative, managerial, and tech jobs for people under 30, those crucial early-career roles, are going to be wiped out.”

For Africa, which already lags behind in the adoption of AI, creating policies that reflect the continent’s position in the face of this powerful technology is even more imperative.

However, major technology and sometimes economic policies in parts of Africa are heavily influenced by foreign frameworks.

Fred Muhumuza, a lecturer at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, echoed this sentiment at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. “African countries need not to copy-paste economic policies adopted by Western economies,” he said. “Over there, the formal sector is big with salaried workers.”

Victoria Fakiya – Senior Writer

Techpoint Digest

Stop struggling to find your tech career path

Discover in-demand tech skills and build a standout portfolio in this FREE 5-day email course

Muhumuza was discussing why African governments should not adopt Western policies in an effort to revive their economies amid the worsening effects of the pandemic. With informal businesses employing the majority of the labour force in Africa, he advocated for more creative, context-specific economic strategies.

Copying policies and the impact

In 2019, Nigeria introduced the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR), which was heavily inspired by Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced a year earlier.

From legal definitions like “data subject” and “data controller” to concepts such as consent, the right to erasure, and cross-border data transfers, the NDPR was clearly modelled on the GDPR, sometimes mirroring its language almost word for word.

This isn’t unique to Nigeria. Across the continent, countries such as Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa have also adopted GDPR-style data protection laws, aiming to align with international standards, enable global business compliance, and signal a commitment to rights-based digital governance.

To an extent, this copy-paste approach has been effective. The GDPR provided African policymakers with a ready-made global standard: comprehensive, enforceable, and principled. For Nigeria, it offered structure to a previously vague legal landscape and helped build public awareness around privacy and digital rights.

Nigerian companies began paying closer attention to how they collect and process user data. The regulation also led to the emergence of local data protection officers and compliance consultants, creating a niche industry.

But the results have been uneven. Unlike the GDPR, Nigeria’s NDPR does not mandate data breach notifications, nor does it impose strong penalties for violations. It also omits important concepts such as children’s data rights and safeguards around automated decision-making.

Essentially, more could be done to localise the NDPR. As the comparison report by OneTrust DataGuidance shows, many of the NDPR’s provisions are either vague or lack enforcement mechanisms.

Copying best practices isn’t inherently bad it can be useful, especially in emerging fields like AI, where domestic expertise is scarce and, as Amodei noted, the risks are imminent. However, the real problem with African policymaking lies in localisation.

Kiito Shilongo, Senior Tech Policy Fellow at Mozilla, warned that the real danger may not be that African AI policies are copied from elsewhere, but that they’re being crafted without meaningful participation from the very people and communities they are meant to protect.

Where are Africa’s AI policies?

According to Diplo, an international non-profit organisation advancing diplomacy in ICT, several African countries have made notable progress in developing their AI strategies or policies.

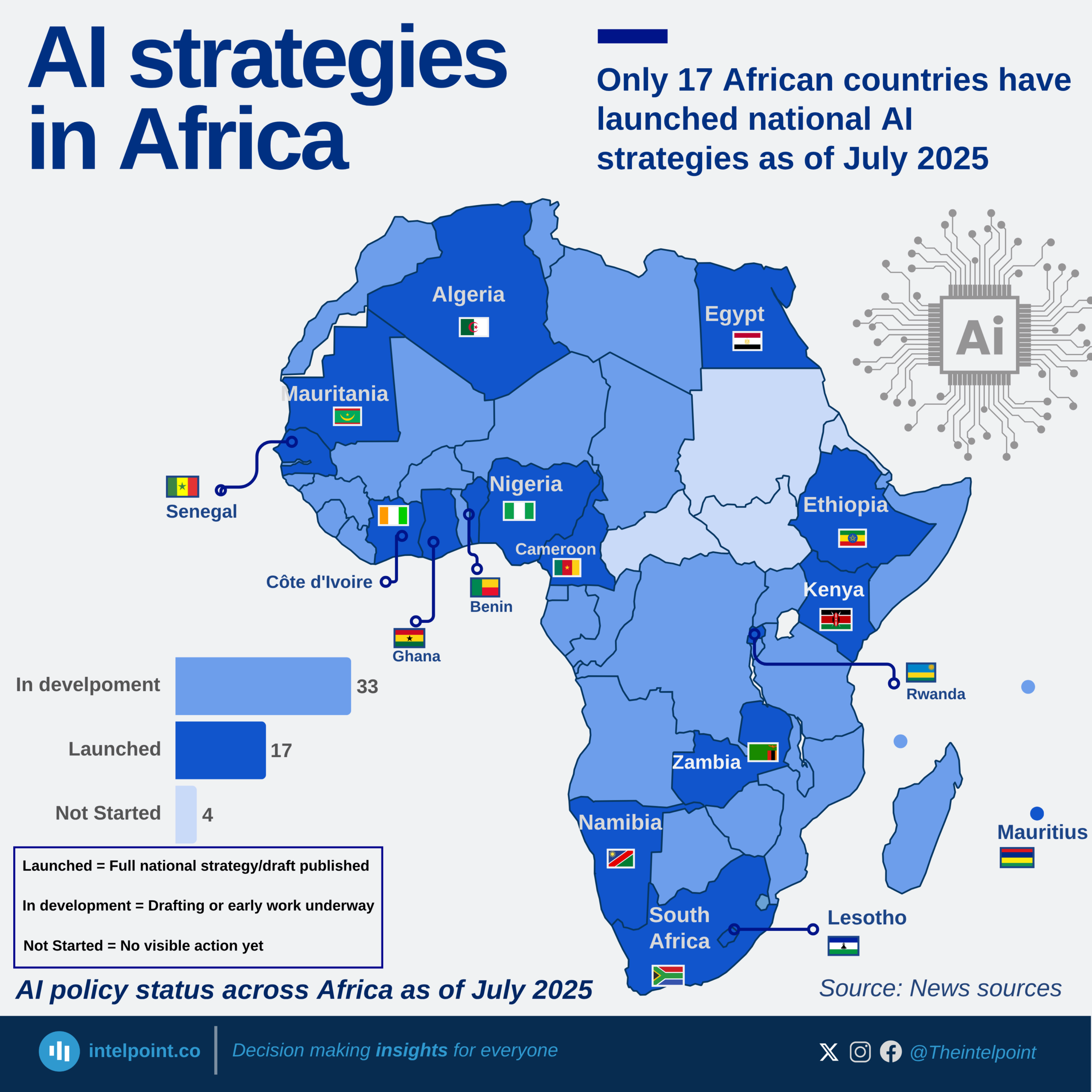

Currently, 17 countries, including South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Ghana, Algeria, and Mauritius, have an established AI strategy or policy.

Mauritius was one of the earliest movers, launching its AI policy as far back as 2018 — well before the AI buzz that followed the release of ChatGPT in 2022.

The strategy highlights AI and other emerging technologies as key tools for addressing the country’s social and economic challenges.

It positions these technologies as catalysts for supporting traditional industries and establishing a new foundation for national development over the coming decade and beyond.

Priority sectors identified include manufacturing, healthcare, fintech, agriculture, and the management of smart ports and maritime traffic.

Similarly, Kenya began exploring AI in 2018 when the government formed a task force to assess AI and blockchain technology.

A year later, the task force released a report proposing that these technologies could enhance innovation and global competitiveness. It recommended investing in digital infrastructure, training, and supportive regulatory frameworks to benefit both businesses and citizens.

By 2022, Kenya introduced a Digital Master Plan spanning the next ten years, which prioritises AI and sets the goal of producing a comprehensive AI master plan.

This plan aims to stimulate local innovation while enabling Kenya to export its AI solutions, and it encourages stronger partnerships with global research institutions to attract new technology and investment.

Across Africa, several other countries have also taken early steps toward AI strategy development. Ghana and Uganda, for instance, participated in a global project in 2019 aimed at helping developing countries create fair and responsible AI policies.

While Rwanda already has a national AI policy, it is still working on a more detailed version that focuses specifically on using AI responsibly to support inclusive growth and development.

Ethiopia has established an Artificial Intelligence Institute tasked with guiding the nation’s AI policies, laws, and regulations.

In South Africa, a 2020 presidential commission report acknowledged the country’s lag in AI development but also highlighted its human capital as a strength, recommending the creation of an AI strategy that reflects national values and a long-term vision.

Cracks in already drafted policies

Like Shilongo, Thompson Gyedu Kwarkye, a postdoctoral researcher at University College Dublin, believes there are deeper issues with Africa’s AI policies than just policy copying.

In his research titled “We know what we are doing”: The politics and trends in artificial intelligence policies in Africa, he examined how the AI policies of Rwanda and Ghana were created and found the development process to be more political than technical or neutral.

In Rwanda, the national AI policy was developed through consultations with local institutions like the Ministry of ICT and Innovation and the Rwandan Space Agency, along with NGOs such as Future Society and international partners like GIZ FAIR Forward.

In contrast, Ghana’s approach involved multi-stakeholder workshops convened by the Ministry of Communication, Digital Technology and Innovations, with participation from the public, startups, academia, telecoms, and government. However, Ghana’s strategy was more development-focused than safety-oriented.

Rwanda’s policy, shaped by the country’s painful history of genocide, leans heavily towards national security, seeing data control as a means of preventing future threats. Ghana, on the other hand, views AI as a tool for attracting international investors and enhancing its image as a forward-looking economy.

Their relationships with foreign partners also differ. Rwanda is cautious and selective, preferring partners that align with its sovereignty and long-term vision. Ghana, on the other hand, is more open and welcoming to international collaborations, viewing them as a springboard for innovation.

Ultimately, developing a meaningful AI policy in Africa is a delicate balancing act — one that requires both strategic vision and local relevance. And according to Shilongo, there are critical lessons governments must learn if they are to get it right.

Copy and pasting is the least of Africa’s problems

In Shilongo’s view, African policymakers should be given some grace because what they are doing is not quite copying.

“What is happening right now is that people from foreign development agencies in different countries like Germany and France get to participate in the process of policymaking.

“They come with knowledge, put forward ideas and the interests of their countries, and they are guided by what they have already done in their countries,” she said.

Agbo Obinnaya, Co-founder and CEO of Nigerian AI startup Case Radar, agrees with her.

In his opinion, the move by African governments to develop AI strategies is commendable, but as a builder, he would also like to have a say in policies that affect startups like his.

Essentially, what a policy looks like is a reflection of who was in the room when it was being drafted.

As an AI policy researcher, Shilongo noted that she and some of her colleagues have attempted to work with the African Union (AU) on multiple occasions, but their requests were not acknowledged. The risk of a policy development system that lacks inclusive participation goes beyond its inability to foster innovation; such policies also fail to protect.

Shilongo observed that many African countries have predominantly focused on economic development in their AI policies, while ignoring the key risks AI poses to human rights and dignity.

There is growing evidence that AI systems display racial and geographic bias, often discriminating against Black people and individuals from the Global South.

For example, facial recognition technologies developed in Western contexts have been found to misidentify darker-skinned faces at significantly higher rates, especially women, with error rates of up to 34% for Black women compared to just 1% for white men.

Similarly, natural language models trained on English-language and Western datasets frequently misrepresent African users and contexts.

“They do mention these things,” Shilongo said. “Ethical approaches to AI and protection of human rights — but where are the institutions to ensure these things?”

The participatory problem is also institutional. Africa lacks the systems needed to ensure broad representation when drafting policies.

“The institutional framework for normal people and normal organisations is not made available — and when it is, it’s too short. You can’t open a consultation for a one-month period; it is not enough,” she said.

Interestingly, the European Union (EU) policies that heavily inspire many African frameworks are created through deeply participatory processes. Shilongo shared that consultation periods in the EU can last up to six months.

“They consider every person, even those who aren’t part of the EU. As long as you feel that the policy will impact you, you will get a chance to be heard.”Perhaps Africa should keep copying — not the policies, but how the policies were made.

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.