Since the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced a cash withdrawal limit for businesses and individuals in December 2022, it has felt like a target has been placed on POS agents.

With an eye on limiting the use of cash by Nigerians, the CBN directed commercial banks to restrict weekly cash withdrawals to ₦100,000 for individuals and ₦500,000 for businesses. That decision would be reversed two weeks later as the withdrawal limits were raised to ₦500,000 for individuals and ₦5,000,000 for businesses.

A currency redesign process announced in November 2022 came into effect in February 2023, putting more strain on individuals and businesses. While virtually every industry in the country was affected, POS agents seemed worse off.

In 2011 when the CBN introduced guidelines for the operation of payment service banks, the hope was that agency banking services would drive the adoption of financial services and deepen financial inclusion in the country.

Although traditional financial institutions have done an excellent job of extending financial inclusion gains, the costs associated with setting up bank branches mean they prioritise areas where they can recoup their investments, thus creating an opportunity for POS agents to thrive.

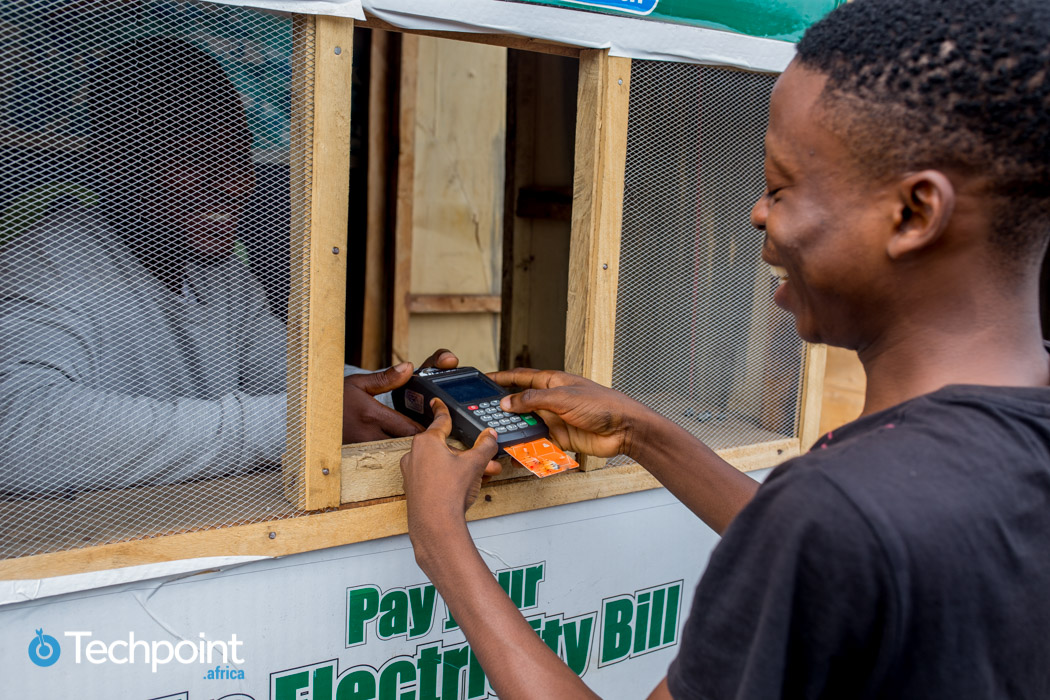

According to data from the Shared Agent Network Expansion Facilities (SANEF), there are more than one million agents across Nigeria. These agents provide services from account opening to bill payments and cash withdrawals. However, these agents are commonly known for cash withdrawals.

In 2021, according to the World Bank, there were 4.3 commercial bank branches per 100,000 people in Nigeria, and more than half are in urban areas. Consequently, POS agents have become a channel to bring financial services closer to the people. However, even these agents are predominantly located in Lagos, with more than 160,000 agents (15%) in the state.

Until the deadline for the use of old naira notes as legal tender, withdrawals at agent locations attracted a ₦100 fee for transactions below ₦5,000, while transactions above ₦5,000 but below ₦10,000 attracted a ₦200 fee.

But as Nigerians have struggled to access cash in the past few weeks, those charges have skyrocketed, with many agents charging as much as 20 times their previous fees. Consequently, the number of POS transactions has grown, increasing month-on-month from December 2022 to January 2023 for the first time in five years.

While it may seem like they have been major beneficiaries of the change, many POS agents have had to shut down their businesses because they can’t access cash.

According to Hussein Olanrewaju, the National Chief Aggregating Officer of the Association of Mobile Money and Bank Agents in Nigeria (AMMBAN), more than 50% of POS agents in the country have shut down their businesses. While there’s no official data on who makes up this number, one can assume that those agents for whom it was a sole source of income were the most affected. Those who remain in business now have to make do with lower transaction volumes as many Nigerians baulk at the exorbitant withdrawal fees.

But how are Nigerian businesses coping with these challenges? For this, we turn to a social experiment by Bolu Abiodun, Senior Reporter at Techpoint Africa. With cash hard to come by, he set out to see how long he could survive in Lagos without it.

He couldn’t pay for a motorbike, and a bus ride using a bank transfer failed because neither the bus rider nor the commercial bike rider liked the idea, citing lost SIM cards, difficulty withdrawing the money, and the possibility of a reversed transaction.

A different set of business owners — food vendors and petty traders — sell products that Nigerians use daily. This group has appeared more willing to embrace alternative payment channels.

A few weeks ago, though I paid for most of my purchases at the local market using bank transfers, many sellers were reluctant. But as it becomes obvious that Nigerians cannot access cash, many have softened their stance. What has been interesting has been their approach. When I tried paying for my purchases, I was directed to a POS agent to whom I made the transfer while he took down the amount transferred. In the end, I paid for items bought from two different vendors to him.

That seems to have been adopted in other markets across Lagos, as this tweet shows.

What lessons could we learn here? While it’s not yet clear whether there’s an effort by the financial institutions that power agency banking services, how these traders are changing the role of PoS agents could be instructive.

Where they previously facilitated withdrawals and the odd deposits, it now appears that a shift to payments could be the future. But how would this work?

From my experience and the tweet above, PoS agents could serve as payment terminals for businesses, enabling them to receive payments. This is important because while fintech founders frequently tout growing smartphone usage in the country, many traders do not use smartphones or even own bank accounts.

Still, this throws up the problem of reconciliation, as mobile banking agents would have to handle numerous payments for the venture to be worthwhile, and manual reconciliation could be tedious. Fintech startups can step in here and build features that enable POS agents to facilitate transactions for multiple parties while handling reconciliation seamlessly.

Businesses, on the other hand, should also be willing to wait for next-day reconciliation, as same-day reconciliation might take some time to be implemented. However, that brings up the question of fund security for businesses, as they may have a hard time trusting that agents would not run off with their monies under the guise of reconciliation.

Is this the end of POS agents as we know them?

That’s a tricky question to answer. In under a decade, POS agents have become a huge part of the financial system. As earlier stated, POS agents would need to handle high transaction volumes for it to make sense financially.

On the other hand, entrepreneurs with smartphones or those willing and able to buy POS machines would not need them. This could open up new opportunities for startups that can enable businesses to receive payments with a smartphone. Even then, this change might only occur in urban areas as it would take some time for rural dwellers to embrace digital payments. Until then, we just may be witnessing a great recalibration.