Another beautiful Japa story! Welcome to a new dispensation! Another friend lost to the West! In Nigeria, seeing these words and variations that are sometimes funny usually indicate that someone else has left the country.

It is common to see these stories across social media timelines. So widespread is their popularity that they often form the topics of discussion in the media and religious gatherings across the country. One could thus be forgiven for concluding that migration is occurring more than ever before in Nigeria.

Some of the discourses present the issue as worrying, calling for concern, while others wonder if there's any cause for concern or if repeated media mentions have conditioned viewers to amplify the situation.

What do the numbers say?

Interested in discovering if the number of people leaving Nigeria is really as high as the reports suggest, I did some digging.

In August 2022, Daily Mail reported that the number of student visas issued to Nigerians going to Britain rose to 65,929, a 686% increase from 8,384 in 2019.

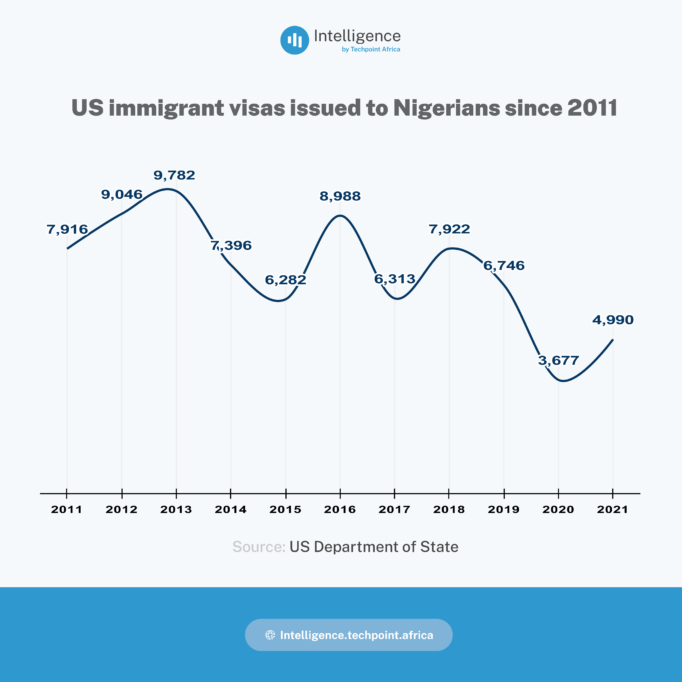

However, figures from Intelligence by Techpoint reveal that the US issued 2,274 immigrant visas to Nigerians in the first half of 2022. For context, in 2019 (the fiscal year that ran from October 1, 2018, to September 30, 2019), 6,746 immigrant visas were issued to Nigerians; in 2021, it was 4,990.

Though these numbers indicate a decline, they don't account for student and other non-immigrant visas, and, thus, don't tell the full story. Though the COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in the number of Nigerians migrating to the US, international immigration to the US had dipped, with the country recording a 48.7% decline in 2021, the steepest in the past decade.

The Nigerian government has pleaded with its doctors and nurses not to leave the country as the sector struggles. As of August 2021, the UK General Medical Council (GMC) revealed that 4,528 Nigerian-trained medical doctors had moved to the United Kingdom to practice between 2015 and 2021. By August 2022, the Punch reported that the number had increased to 10,096.

Although there are no stats to support the claim, this Bloomberg piece — based on comments from Sterling Bank's CEO, Abubakar Suleiman — claims that Nigerian banks are also experiencing a massive loss of talent. It is, however, not clear if the talent remains in the country but simply changed jobs or locations.

Suck at managing people?

Give it a try, you can unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

So what's the big deal?

Understanding that these terms – mass resignation, brain drain, and talent exodus – suggest a significant migration of citizens in search of professional opportunities, what should we make of these numbers?

Olawale Osoba, an economist and management consultant, believes we can't claim to be experiencing an exodus because the migration frequency isn't significant enough.

Nigeria has a population of over 200 million and a minimum employment rate of 25%, with Statista putting the number of working Nigerians in 2022 to over 67 million. A look at the available migration stats shows that less than 0.1% of working Nigerians are leaving the country. (This is me giving it a long rope and estimating that 100,000 migrated in the last year.)

Fred Swaniker, Founder and CEO, African Leadership Group (ALG), agrees with Osoba. He questions the possibility of a nation with a large young population having a talent shortage because of a few migrants.

Meanwhile, Rachael Onoja, Director of Learning, AltSchool Africa, admits that there might be a talent shortage for some specific roles in some sectors, which might not necessarily translate to a brain drain. From what she’s noticed with engineering talent, more mid-level and senior-level engineers are migrating than junior ones, causing a deficit that sometimes takes months to fill.

If, as some believe, losing the educated but unemployed population to migration might cause a greater drain than losing professionals would, companies' willingness to upskill junior level and hire entry-level talents might cushion the effect of losing senior employees.

Osoba points out that the statistics seldom capture, if at all, immigrants in Nigeria and returnees.

One thing that Osoba, Swaniker, and Onoja agree on is that the global job market is competitive, and Nigerians migrate for different reasons.

What is responsible for talent migration?

People migrate willingly or of necessity and there are distinguishing features between nations losing more human capital and those gaining them. According to this report, stable fiscal economies, better education, political stability, healthcare, and security are a few advantages that some countries have over others that make them attractive to immigrants. Swaniker agrees with this.

"If I were to describe it, I would say that the primary cause of ‘brain drain’ for young people in Africa (and what ultimately drives them to relocate) is ‘lack of opportunity.’"

Meanwhile, receiving countries put policies in place to attract migrants to meet their human capital needs. Canada and the UK, for instance, are attracting immigrants for economic recovery and long-term prosperity, using point-based immigration systems and offering permanent residency to certain economic classes.

Among other things, Nigerian talents are searching for locations with more conducive fiscal conditions and education opportunities. According to Onoja, exceptional talents don't find job fulfilment at local companies.

She adds that there are some unfavourable government policies and infrastructural deficits -- electricity and internet -- that could affect productivity. Then, there's the case of the government handing big projects to foreign companies.

When there's a case of talent migration in a country, governments and stakeholders often try to investigate, consider the potential implications, and devise possible ways to stop it. Suleiman stated that there’s a plan to “drive the process of training more skills in the area where we see deficits.”

Osoba mentions that the problem appears to be a skewed distribution of opportunities for the available talent pool. As far as he is concerned, locations like Lagos are heavily congested, and that includes a strain on opportunities, even though supply is spread across the country.

Onoja makes a case for what it takes to get experienced engineers and how companies might be unwilling to upskill their talent.

What role do talent training and outsourcing companies play in talent migration?

A typical selling point of talent training and outsourcing outfits is the possibility of placement in global companies. So, the question is, are these companies not enabling talent migration? Osoba shoots down this argument and calls the world an open market where the competition for human capital is not restricted to the talent’s country.

Swaniker is also quick to add that outsourcing companies are not the enemy. And Onoja agrees with this, saying companies like TalentQL and ALG prepare talent to be fit for global opportunities. She further notes that "exporting local talent means exporting quality and culture."

Swaniker makes reference to Nigerian musicians and how they are pushing afrobeats beyond Africa's borders. Blaming founders' mindsets, he mentions why employers should be more fluid in the way they see talent migration. He points to how beneficial this has been to countries like India and China and touches on the possibility of an inflow of foreign remittances. He also believes that talent could "bring back valuable skills, capital, fresh ideas, and networks that can help catalyse innovation and entrepreneurship."

However, Osoba does not agree completely with this. He questions Nigerians' patriotism and submits that there's a slimmer chance that there'll be many returnees willing to power the economy.

This piece has focused on talent migration while reflecting the thoughts of stakeholders in the talent outsourcing and startup scene, the next article in this mini-series will explore how companies can handle talent migration.