Key takeaways

- Nigeria’s film industry has evolved from Yoruba travelling theatre companies in the 60s to movies made exclusively for streaming platforms today.

- More Nigerian filmmakers are choosing to pitch their tent with streaming video-on-demand (SVOD) platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Showmax, and YouTube. This in no way helps Nigeria's cinema-going culture, which already faces issues like affordability.

- SVODs like Showmax believe that local content is still king across African markets, but some critics think that it's still a long way off from being the panacea for low subscriber numbers.

Nigeria's film industry has seen some epoch-making dates. From the first Yoruba travelling theatre companies to the 1992 version of Living in Bondage becoming the first blockbuster home video.

Recently, we've seen streaming giant, Netflix, acquire films like acclaimed actress, Genevieve Nnaji's Lionheart.

We've also seen Funke Akindele's Omo Ghetto - The Saga become Nigeria's highest grossing film, closing at ₦636.1 million.

Last month, Amazon Prime Video launched in Nigeria, announcing one Amazon Original, Gangs of Lagos, starring Adesua Etomi, Timini Egbuson, among others. It would also premiere the Nigerian version of comedy show, LOL: Last One Laughing

Early this year, MultiChoice-owned Showmax aired The Real Housewives of Lagos, a show which trended on Twitter for 15 hours before its launch. Interestingly, the streaming company recently announced the appointment of its first Nigeria Country Manager, Opeoluwa Filani.

As Filani told Techpoint Africa, Showmax plans to double down on local content, a strategy the company believes has worked quite well in Nigeria and other African markets.

To understand the big draw on local content for these streaming platforms, we might need to take a history lesson.

Sometimes we rise

The film industry has seen greats like the late Duro Ladipo, one of the founding fathers of Nigeria's performing arts, who received the Nigerian Federal Government Cultural Achievement award in 1963 for his play, Oba Koso (The King Did Not Hang).

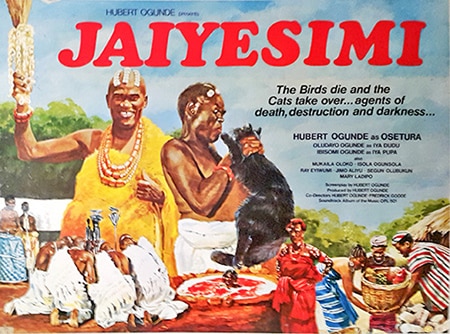

Then there was the late Hubert Ogunde. He is regarded as the pioneer of the travelling theatre group in Nigeria. Ogunde recorded several of his plays on celluloid, one of the first to do so.

Be the smartest in the room

Give it a try, you can unsubscribe anytime. Privacy Policy.

Fun fact: Celluloid was first invented in 1856 and is the first synthetic plastic material. Before being used to make films, it was an inexpensive imitation of ivory, tortoiseshell, and even linen, and was used for things like jewellery, greeting cards, toys, and billiard balls.

Fun fact: Ogunde made films like Àiyé, Aropin N'Tenia, Jaiyesimi.

It also had the likes of Adeyemi "Ade Love" Afolayan, Ola Balogun, Eddie Ugbomah, Ladi Ladebo, Moses Adejumo, Adebayo Salami, and Afolabi Adesanya.

Between the early 70s and early 80s, films like Kongi's Harvest, Jaiyesimi, Cry Freedom, Bullfrog in the Sun, and Bisi, Daughter of the River had their day in the spotlight.

Before this period and prior to Nigeria's independence in 1960, though movies were shown in what passed as cinemas, Nigerians were not allowed into these viewing halls.

The 70s and 80s were a turning point for the Nigerian cinema industry, especially due to the oil boom which saw many people flush with disposable income. According to Motunrayo, a Nollywood enthusiast, some of the cinemas which sprung up were owned by Lebanese settlers.

And sometimes we fall

However, as the country suffered through years of military rule from 1966 to 1999, with a brief respite from 1979 to 1983, cinema culture declined as ruling governments took over the cinemas owned by foreigners.

In 1972, Head of State, Yakubu Gowon enacted the Indigenization Decree, causing over 300 film cinemas owned by foreigners to be turned over to locals.

It was this void that direct-to-video films — popularly known as home video — like Living in Bondage directed by Kenneth Nnebue in 1991 came in to fill. The movie was the first home video to record massive success, and soon, anyone with a camera started making movies. It didn't also help that technological advancements allowed people to pirate films made on celluloid.

Fun fact: The National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB) verified and approved 890 home movies from January to June 2022, compared to 182 in the same period in 2019.

"They were the ones who disrupted the system such that they didn't shoot their movies on film, they didn't care about the sound. They just went, got cameras, shot, edited, put it in the market, and it became popular.

"People saw that they didn't have to go to the cinemas," Motunrayo explained.

While home videos boomed, the local cinema industry suffered. As usual, foreign movies were available to watch and many flocked to see them, but the indigenous films received very little attention.

Also, with pretty much anyone with access to video equipment able to shoot a home video, quality dropped.

But in 2006, Kunle Afolayan, son of Ade Love, released The Figurine — regarded by many as the dawning of a new era in the film industry — which grossed ₦30 million in the cinemas.

The now

In May 2022, Nigeria's Minister of Information and Culture, Lai Mohammed asked streaming platforms to increase their local investment, including opening offices and increasing the local content on their platforms, if they wish to do business in Nigeria.

Since then, we’ve seen streaming platforms like Amazon Prime Video launch in the country, and Showmax hire its first Nigeria(n) Country Manager, Opeoluwa Filani.

Interestingly, most of these streaming platforms have shown an affinity for local content.

These platforms bring funding to the table, and there are currently over 100 Nigerian movies on Netflix, including Originals.

Netflix has signed partnerships with filmmakers like Kunle Afolayan, Kemi Adetiba, and Mo Abudu. It has also struck deals with film houses like Inkblot Productions.

It also partnered with FilmOne Entertainment, a deal that has seen the platform add five to ten Nigerian movies every month.

The average licensing fee Netflix pays is between $10,000 and $90,000; substantial, but not as much as it spends on films in Asia and Europe.

Motunrayo, however, worries that these companies may have only traded slave masters.

"By the 2000s, the marketers became king. Marketers would call producers and give them money."

"We keep exchanging an overlord for another overlord and exchanging mediums for other mediums. Instead of maintaining the mediums and helping promote cinema culture.

"Many of our filmmakers are not going to the cinemas for a while, and it's sad."

These marketers soon grew to become dictators in the film industry, slapping titles like executive producer on themselves, deciding who would be in films, and sometimes even banning some actors.

However, some of them began making their own movies or got roles in films that were not controlled by these gatekeepers.

Eventually, MultiChoice-owned Africa Magic came on the scene in 2003 and began paying Nollywood producers to make films for them.

As Motunrayo told me, some filmmakers also receive funding from the government, like Kunle Afolayan, Kemi Adetiba, and Tunde Kelani.

Then video-on-demand platform, Iroko TV launched in 2011 and also became another source of funding.

Would local content help streaming platforms?

Looking through the Google Play Store, we found several streaming apps claiming to either be subscription-based or free which allowed users to stream African content alongside foreign content.

Some had been downloaded up to a million times.

We also found Northflix, a streaming service dedicated to the Kannywood — movies made in Hausa language — industry. The company claims to have 10,000 paying subscribers across 85 countries. Interestingly, it appears the app is no longer available for download on the Google Play Store, but can still be downloaded on the Apple App Store and CNET’s store.

On the bigger fish side of the spectrum, Amazon, Netflix, and Showmax continue to spend money on acquiring movie licences and making Originals.

Talking with Filani, he emphasised that the company would continue producing local content and work with local producers, with plans to launch several Nigerian shows in the coming months.

According to Filani, African content is king across all of Showmax’s markets, receiving more viewership compared to foreign shows. The plan to double down is backed by internal research confirming the superiority of local content.

"Based on a research we did at the end of 2021, local content came up tops, across all the markets, whether in Nigeria, Kenya, or South Africa."

Another surprising addition to the equation which appears to validate this theory is YouTube.

In recent times, many Nigerian filmmakers have taken to releasing movies on YouTube, with many of them garnering millions of views in under a week.

Some have become full-fledged YouTube-release-only channels. Also, some banks have caught on to this trend. Access Bank-owned Accelerate TV operated as a YouTube Channel since its launch in 2014 before transitioning to a streaming service in June 2022. As of press time, the channel had over 30 million views.

Red TV, United Bank for Africa (UBA)’s media outfit, has over 56 million views. GTCO's Ndani TV has more than 100 million channel views.

However, many of these YouTube releases are what Mr C of Iroko Critic fame called Asaba-type of movies: cheaply and quickly made.

"There's definitely a market for Nigerian content. Nigerians in the diaspora are probably the biggest market for Nigerian movies."

Interestingly, as of press time, half of the top 10 movies trending on Netflix in Nigeria were Nigerian movies; the rest were American, Korean, and French.

No Nigerian TV show/series made it to the top 10 TV show list.

Referring to this, Mr C said, "That's what you are competing with. When you think of streaming in terms of Spotify, Burna Boy isn't competing with just Davido; Burna Boy is competing with every musician on the platform. Unfortunately, our movies aren't there yet."

Local content on these platforms is competing with global shows. In Motunrayo's words, people are spoiled for choice, a situation that is the result of a streaming platform's major value proposition: variety.

In Nigeria, many people still get their movies from illegal sites or watch for free on YouTube. Except by some stroke of luck, the country's contribution to the 26 million African video-on-demand subscribers by 2026 might be very abysmal.