In big cities with diverse tribes and multiple nationalities, there’s nothing quite as breathtaking as cultural festivals, which bring various forms of creative expressions to life. People choose to show their cultural heritage in diverse ways, and in Nairobi, Kenya, two dynamic entrepreneurs chose the sprawling beauty of fashion with Genteel.

This could be a story about any other creative brand, but, as you would soon discover, the startup is making a big statement in Africa’s creative industry, which still has so much unrealised potential.

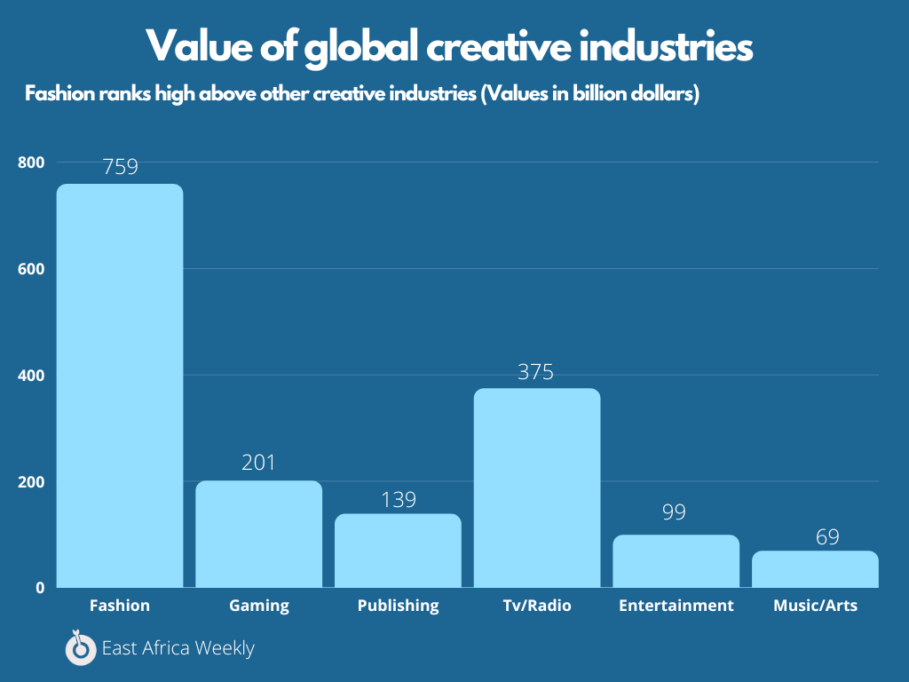

Depending on the sources you trust, the global creative industry, which includes fashion, film, and TV/radio, stands at a massive $2 trillion – $3trillion. Interestingly, the fashion industry takes up a massive $759 billion, with TV/radio coming the closest, with $374 billion.

From the sparse data on Africa’s creative economy, we could see that music, deemed one of our biggest exports, generated $101 million in revenue in 2019. And analysts estimate that this will reach $500 million by 2025. The continent’s film industry is worth $5 billion out of a potential $20 billion.

Once again, somewhat surprisingly, fashion leaves the others behind with a market value of $31 billion, according to Afdb’s 2013 figures. While this might seem like a while ago, it’s important to note that Africa now generates $8.8 billion in fashion exports compared to $2.5 billion in 2013. If the math makes sense, we’d now place the value at $109 billion.

Though these numbers might seem impressive, they were not on Sam Jairo’s mind when he started a thrift clothing business in Gikomba, a huge market for secondhand clothing in Nairobi. Proximity to Gikomba fuelled his interest in fashion, and appeals from friends made him start the business while studying business information technology at Strathmore University.

“My family saw I was interested in what I was doing, so they gave me an opportunity to travel to Istanbul, Turkey, where I technically got the opportunity to start importing clothes into Kenya,” Jairo explains.

However, this opportunity revealed a problem which brought the light bulb moment for Genteel. Some clothing would fit, but others wouldn’t; usually, this happened with the tops and bottoms of the same clothes.

“I realised that part of this problem was because most of the items that are imported in this country were made for Caucasian body types. We Africans have broad hips and shoulders, which is not technically factored into the items that are made.”

This realisation led Jairo on a journey of deep research to uncover the requirements to build a fashion brand.

Brands from other countries have dominated global fashion conversations. You’d be hard-pressed to find young Africans pining over prestigious brands like Imane Ayissie or Christie Brown when they could chase Gucci.

“I started a journey trying to understand how to create a fashion brand that is not only inclusive but has a distinct cultural identity. I studied two brands, Henry Poole and Gieves & Hawkes, and then I began the process of creating something that is intrinsically African. How can we incorporate African culture into the pieces we already have?”

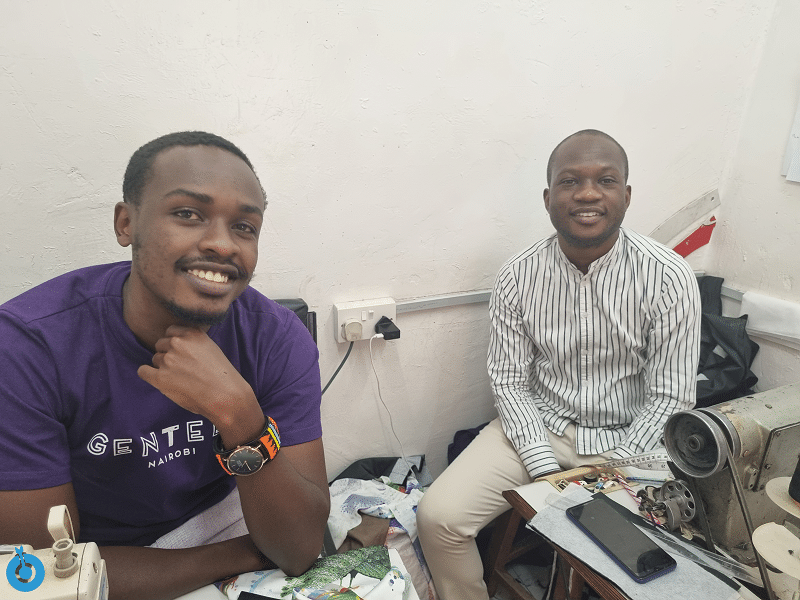

Jairo soon approached Brian Baliach, a fellow student and thrift trader, and they formed Genteel to use clothing to tap into the African consciousness. The brand has since grown in popularity and received heavy validation after making the clothes of Kenya’s President, Uhuru Kenyatta.

While clothing the president is newsworthy, few understand how these flashy suits are made.

How Genteel works

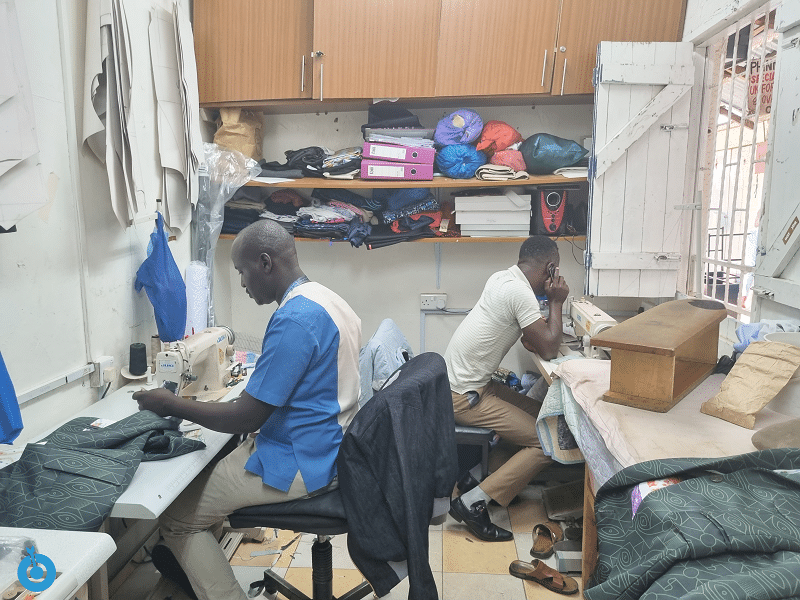

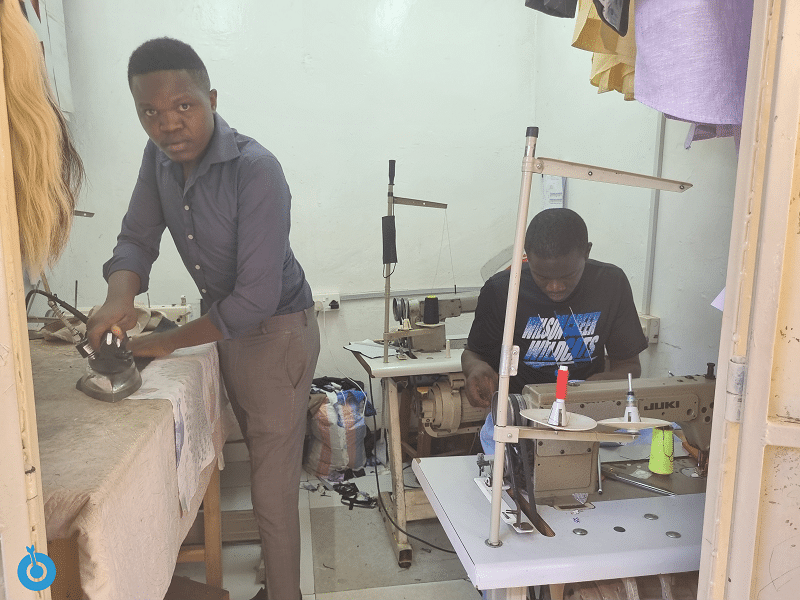

To the outside observer, Genteel is a classy fashion brand with a website and store at Gigiri, home to a large ex-pat community in Nairobi. But there’s a whole process behind the scenes that leads from the luxurious parts of town to the slums of Kibera, home to several informal businesses, including tailors.

Since its inception, the company has made informal tailors serve a professional brand looking to provide world-class apparel service to high-net-worth customers.

“If you come in contact with our brand through social media, our website, or Google, you book an appointment. We ask you to come to our store, or we come to you, so you select a fabric. We take measurements, give you a timeline, and ask you to pay a deposit.”

At this point, the Co-founder and Director of Operations, Baliach, steps in.

“We get the information from our team at the shop about the fabric the client has chosen, and we have a database where we store all the measurements. We then use Trello to create cards for each client and organise the work for the tailors,” Baliach explains.

When the work is ready, the company uses delivery services to get the apparel to its client.

Beyond bespoke fittings, the company also runs an eCommerce website where clients can place orders for various clothing items and get them in five days. Depending on income class, Genteel’s ready-to-wear products retail for as low as 5,000 ksh ($46) to 143,000 ksh ($1,212).

Excitingly, the startup is collating a measurements database to aid its eCommerce process, creating room for fashion management software.

“We’ll use the data to create a Kenyan size chart. Most of the measurements you see are for the US and the UK. When you say small, medium, large, extra, it means different things for Africans.”

Anyone familiar with the startup world in other climes would probably ponder the scalability of Genteel’s business model. Unlike the likes of Uber, the tailors are full employees, not freelancers or contractors.

The typical scenario would be for a company to build software connecting users to service providers, but the African market has not smiled on this model.

How then would the company grow as fast as most startups often do?

Jairo admits that while the startup is currently big on bespoke wares, to scale, the focus would have to be on ready-to-wear products on its website.

“We would create a finite number of products, market them, and then receive orders through our digital platforms; it’s easier to have that. And it opens up opportunities for distribution as opposed to the bespoke model, which is very highly personalised.”

However, he maintains that the company has considered the marketplace model but will be sticking to a more measured approach to preserve the brand aesthetic and story.

A Kenyan investor, who chooses to remain unnamed, highly supports Genteel’s hands-on approach, arguing that you can only build a quality marketplace model when both ends of the spectrum are sufficiently developed.

“Without the infrastructure and systems in place, what are you connecting to what?” they ask.

Of course, it’s never easy

So far, I’ve not met anyone without terrible tailor experiences, emphasis on experiences. Be it unnecessary delays or clothes that would make other people ask, “Why bother?”, or “Who did you offend?”

You can imagine my surprise when Genteel’s co-founders told me they would take me to Kibera, where they make their awesome apparel.

“We’ve had to canvas the brand of professionalism that exists with informal tailors and try, as much as possible, to give a professional outlook to prevent clients from having to deal with experiences such as unmet timelines,” Jairo poses.

Adding this to the fact that neither co-founder studied fashion in school, their learning curve was painful, especially when trying to understand the technical details while delivering solid products to customers.

Also, the startup has to deal with the cost of importing quality industrial sewing machines, which are priced as high as a million Kenyan shillings ($8,500). Per Baliach, getting the investments and funds to procure more sophisticated machines has been challenging. And the lack of investment to meet these needs has, so far, kept the startup from profitability.

However, Genteel can point to some significant wins along the way.

Before fitting President Uhuru Kenyatta for a European outing, the startup had already amassed a database of 250 clients for the bespoke model and up to 2,500 clients from its website.

The startup has received recognition for its efforts from the British Council Connect and won grants of up to $25k. It projects to make at least $100k in 2022, up 30% from last year’s haul.

Perhaps, most importantly, bringing Genteel to Kibera has helped the professional careers of some informal tailors. One such tailor, Martin — a husband and father of two — who went into tailoring after finishing secondary school, speaks highly of Genteel.

“In the process of working, we keep on learning. Here in Genteel, we’ve been working professionally, but where some changes are needed, we do it as requested. Now I don’t have to worry about getting clients; they just bring fabrics and measurements and you arrange yourself to work.” Martin says.

While Genteel impacts the lives of tailors like Martin, it plans to keep its head down on fine-tuning its manufacturing process and improving distribution within Kenya.