Unless you have a passion for medicine and healthcare, you probably wouldn’t like visiting hospitals. Barring a few exceptions, a Kenyan, or any African hospital visit for that matter, will almost always be unpleasant. And this unpleasantness gets magnified tenfold should you need medical attention.

Even when you’re not taking in the sight of human pain and suffering, the lack of medical facilities and long queues will, most likely, discourage anyone from going.

Against this backdrop, Tibu Health — a startup we met during our brief visit to Kenya — caught our attention. Tibu Health takes away the long queues and inefficiencies that plague Kenya’s healthcare sector by coming to your doorstep. That’s the gist, but let’s go deeper.

The numbers do not tell a pleasant story, but we’ll need to glance at Kenya’s health system to understand them.

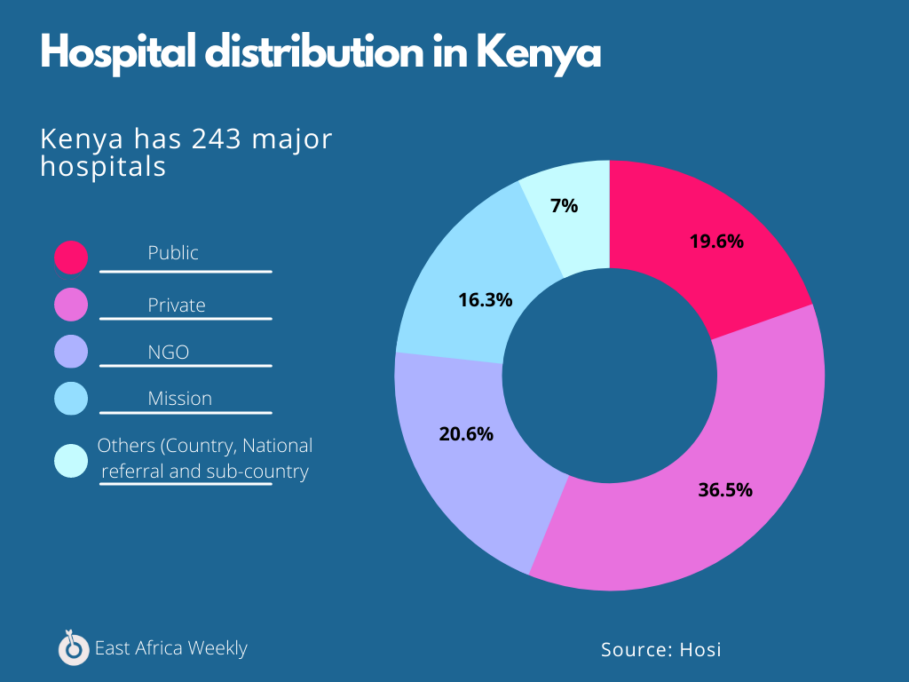

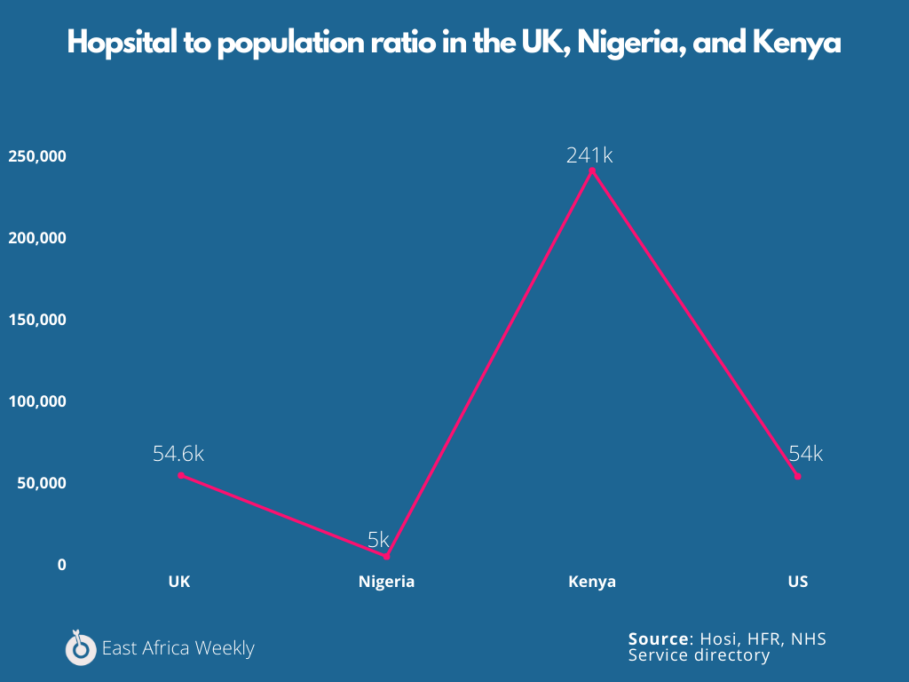

Kenya divides its hospitals into six levels. Levels 1 and 2 are community dispensaries and clinics, respectively, for primary health care, and it progresses up to level 6, which features highly specialised referral hospitals. Hosi, a collaborative hospital listing and review platform, places the number of Kenyan hospitals at 243 across public, private, NGO, and faith-based, among others.

Hosi does not record community facilities and dispensaries (levels 1 and 2) in this report, and it begins its records from small hospitals with minimal healthcare facilities.

From these figures, we can surmise that there’s 1 hospital serving 221,275 people in Kenya, but that doesn’t paint the full picture of the country’s healthcare system.

The UK, for instance, lauded as having one of the world’s best healthcare systems, has 1 hospital serving 54,000 people. In contrast, Nigeria has 1 hospital for 5,000 people but still ranks slightly lower than Kenya and way lower than the UK in global healthcare indexes.

How can this be, you ask? Well, delivering quality healthcare requires more than establishing hospital units and filling them with beds. We need to consider medical infrastructure, healthcare professionals, costs, medicine availability, and, most importantly, preventive measures.

We would need a special article to dissect these numbers fully. However, the figures that stand out show a clear gap in regulatory focus between Kenya and a first-world country like the UK.

Let’s take hospital beds, for example. We keep talking about them because they improve a doctor or nurse’s ability to treat a patient when used to their full capacity. A bed, in this context, ideally refers to one that is fully staffed, funded, and available for use by the patient.

Following the COVID-19 crisis, most African hospitals, Kenya’s included, faced a huge dearth of hospital beds. We should point out that Kenya was one of the better prepared African countries to face the pandemic.

So far, Kenya has 1.4 beds for 1,000 people, less than the global average of 2.3 beds for 1,000 people. By comparison, the UK has 2.4 beds for 1,000 people, which is slightly higher than the worldwide average. But the scenarios in both countries are different.

The UK is seemingly following the mantra: Why build more hospitals or buy more beds when you can put wellness measures in place to prevent people from going to the hospital in the first place?

In recent years, the UK’s policies have actively reduced the number of hospital beds in favour of providing care that reduces the demand for hospital facilities and faster discharge. This initiative is not without its problems, but the country has been able to double down on other facets of healthcare.

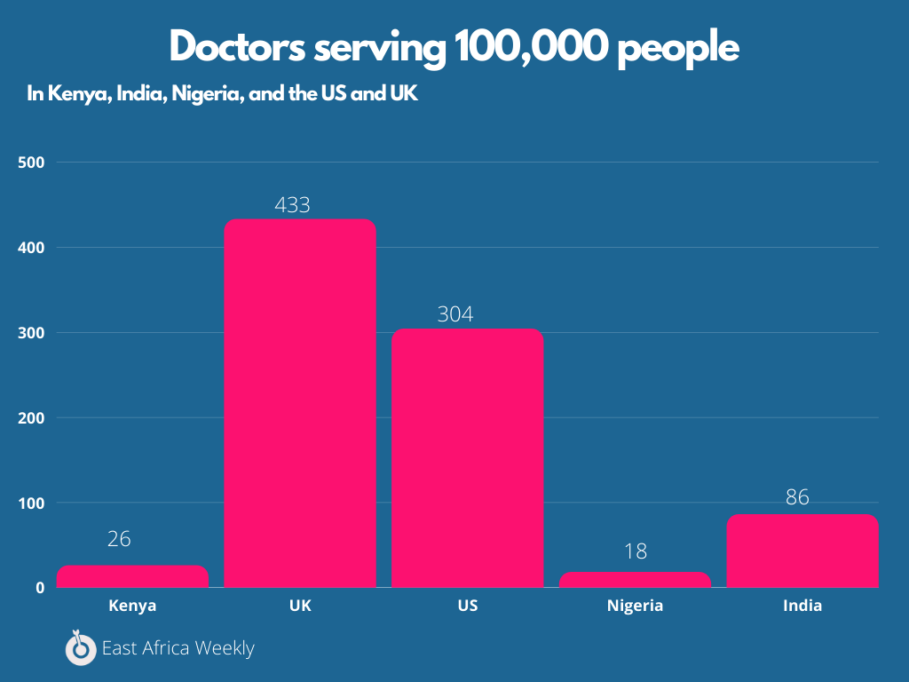

While Kenya has just 26 doctors serving 100,000 people, the UK has 443 for the same number of people.

While one country has actively recruited doctors to boost its healthcare, the other has made some confusing moves.

With a less than ideal health situation, it has fallen to entrepreneurs to make the healthcare space in Kenya more exciting. A recurring trend across the continent.

The Tibu Health gameplan

Before coming to Kenya in 2013, Jason Carmichael worked with an NGO to tackle a cholera outbreak in Northern Sierra Leone. He arrived in Kenya to work with AMREF as a public health grad student, but he began to notice the painful gaps in healthcare delivery.

Carmichael observed that most doctors did not work full time, and those who did couldn’t work to their full capacity, so there were barely enough to cater to thousands of people.

“We saw some supply and demand-side problems early on that we wanted to further investigate and test to see if we could put any model around it and monetise it while at the same time solving an important public health problem.”

Having such lofty ambitions, the technology to execute this at scale would be a tall task. Luckily, he met the illustrious Peter Gicharu.

Born and bred in Kenya, Gicharu met Carmichael in 2017. At the time, Gicharu was neck-deep in building tech solutions, providing solutions including livestock management systems, and tracking systems for different companies and individuals.

“The part that attracted me most about the solution [Tibu] was the challenging bit that went along with it. So the tech implementation at the time, I thought it was a bit crazy since no one had actually tried to embark on such a journey. Having a practitioner come to your place was unimaginable, and no one had tried it. So to me, it was very interesting,” Gicharu revealed.

Tibu heath’s first iteration worked more like on-demand healthcare delivery, just how you would place an order and get matched to a driver on Uber. Before launching, all their dutiful surveys and data gathering showed that people wanted an on-demand service, so they went all in.

But Carmichael and Gicharu were in for a surprise.

“That assumption was pretty quickly vanquished. We found out the market was in need of a scheduled approach where they didn’t need the doctor right away. But they’d like for them to come to their place, say, next week or at the weekend so that they can free up a schedule to accommodate that,” Carmichael revealed.

But how does it fare in the Kenyan space?

How does Tibu Health work?

Since that initial phase, Tibu Health has evolved into a more dynamic startup. Through its website, mobile app, SMS, or email, prospective patients can book various services like home consultations, lab work at home, COVID-19 tests, and special services.

“Once that gets to our end, our patient support representatives engage the patient. There’s a triage process from the call to dispatch where we see whether we need to send our practitioners over; we do not dispatch for emergencies. In cases of emergencies, we recommend our patients actually seek medical assistance from the nearest facility,” Gicharu explained.

“So you don’t want someone who is bleeding out to wait for your services when they need instant medical attention.”

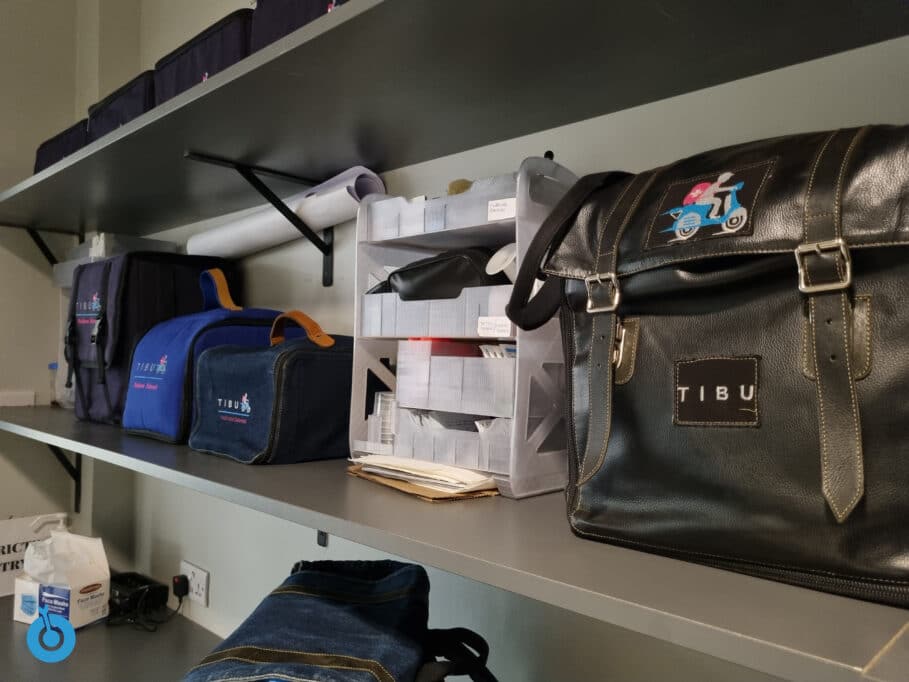

Once the team determines it can attend to the patient, they deploy the required medical practitioners armed with the appropriate kit. Did I say kit? Yeah. Apart from its telehealth platforms, Tibu Health’s medical practitioners are armed with a backpack containing items you’d typically find in clinics.

“We call it a clinic in the form of a backpack because it has everything you would need to operate a clinic. There’s a small backpack that lets us do labs, take vitals, and diagnose. For sample collections, they have everything they would need to collect samples and send them to the lab for testing.”

Tibu health’s doctors can write prescriptions, and its partnership with some pharmacies allows speedy prescription delivery. Patients can pick up their prescriptions elsewhere if these partner pharmacies are unavailable. In the case of surgeries, patients are referred to the nearest hospital.

Running around Nairobi typically takes 30 mins to 60 mins, so Tibu’s drivers get around in a car or a bike, depending on the type of kit in use.

Interestingly Gicharu claims that no other company is currently offering what Tibu offers, and the few that tried this have had to pack up, given how difficult the space is.

“Apart from that, there’s also telehealth which is quite constrained. It isn’t as detailed, but we offer an opportunity for the practitioner to be with you, examine you, and treat you accurately. As opposed to you explaining your symptoms over the video, which has been a huge hindrance.”

He also adds that telehealth is just one feature out of several that will act as a support for its core business.

What Tibu health addresses

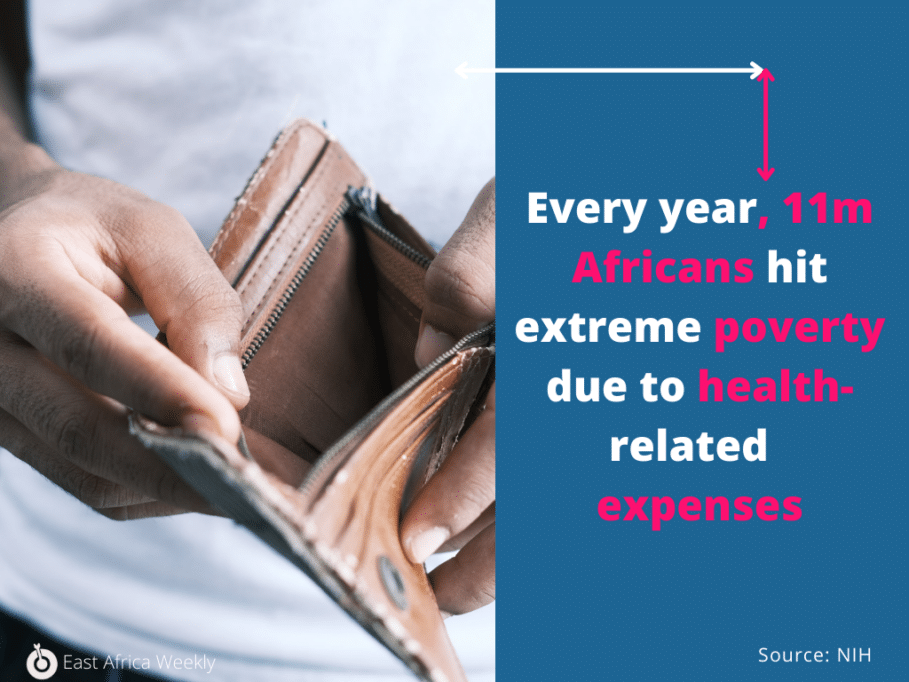

In addition to the healthcare difficulties we listed above, it’s estimated that 450,000 Kenyans are pushed into extreme poverty every year due to health-related expenses.

Seeing a general practitioner would typically cost upwards of Ksh 1,800 ($15.4) to Ksh 3,000 ($2,567) while visiting a specialist starts from a minimum of Ksh 3,600 ($30.8). These amounts might seem small for some, but this is quite significant for a country with 16% of its population living on less than $1.9 a day.

Tibu’s home consultation costs Ksh 1,850 ($15.8), an amount Carmichael claims is too cheap for the quality of healthcare on offer.

“Having a high-end doctor at home doing head-to-toe consultations. That’s high-end concierge medicine for less than $20, and we’re currently 20% cheaper than what’s currently available in the market.”

Carmichael maintains that the company can beat down costs because it has fewer operational costs than a standard brick and mortar hospital. In his words, the medical kits can do 80% of what is done in the clinic.

Employing this method has helped the company break even three times since its 2020 launch and increase revenue by over 236%. But there’s still a huge part of the market up for grabs. Insurance would make Tibu’s proposition a no-brainer for most patients, but it remains out of reach.

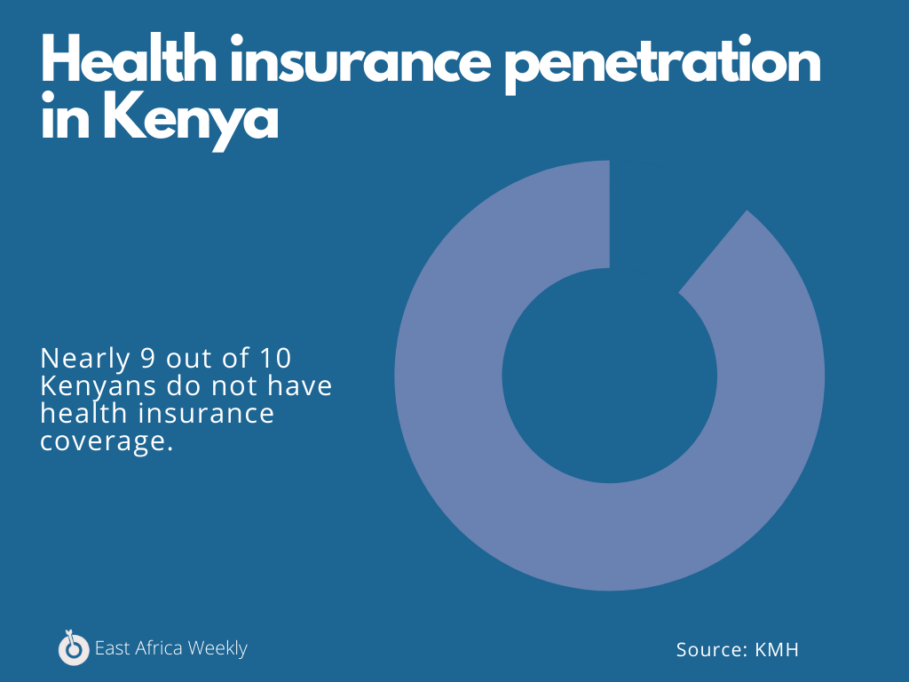

However, at 11%, insurance penetration in Kenya is still very low. Carmichael seems to think that there’s an apparent lack of accountability in the insurance sector, and most are not willing to take a chance on a healthcare model they are unfamiliar with.

“The reality is our model can virtually eliminate fraud. It can save lots of money for insurance companies because we don’t have this big health infrastructure, and we increase access points to healthcare services.”

Tibu currently partners with nine insurance companies, most of which are global, but two are in Kenya. While countries like Nigeria have a cultural issue with insurance, Carmichael insists that Kenya’s insurance gap is mainly institutional.

“The mindset [of insurance practitioners] needs to change to more proactive and progressive. So they can leverage new models and work to make the insurance sector and health system more efficient, more transparent, less corrupt, [and] less wasteful.”

While Kenya has a massive physician deficit, Tibu is hiring for many roles, including tech and design. The company shores up against inevitable losses to big tech by creating a talent pipeline where junior developers are hired and paired with senior developers to gain experience.

So far, the model has worked, and the startup has gained up to 20,000 patients since its 2020 launch. Though there’s some investor push for Tibu to launch in West Africa, Carmichael insists they would rather close in on East Africa and understand it.

“Our first objective is to expand our footprint and expand the service offering within Nairobi so we can capture more of the market. After that, we’re looking at different towns within Nairobi. And we’d like to plant the flag in Rwanda and South Africa within the next year and a half or so.”

Interestingly, Tibu health’s founders are not so keen about raising money and have chosen to focus on bootstrapping rather than taking the popular route he describes as a PR play. In November 2019, it raised $100k, and a little more a few months later, but all under a million dollars.

However, for Tibu to make a dent in Kenya’s health sector, its services would need to be more widespread and available to counties outside of Nairobi. In summary, we’re saying Kenya needs more of Tibu or more startups like it.