First of all, a bit of background.

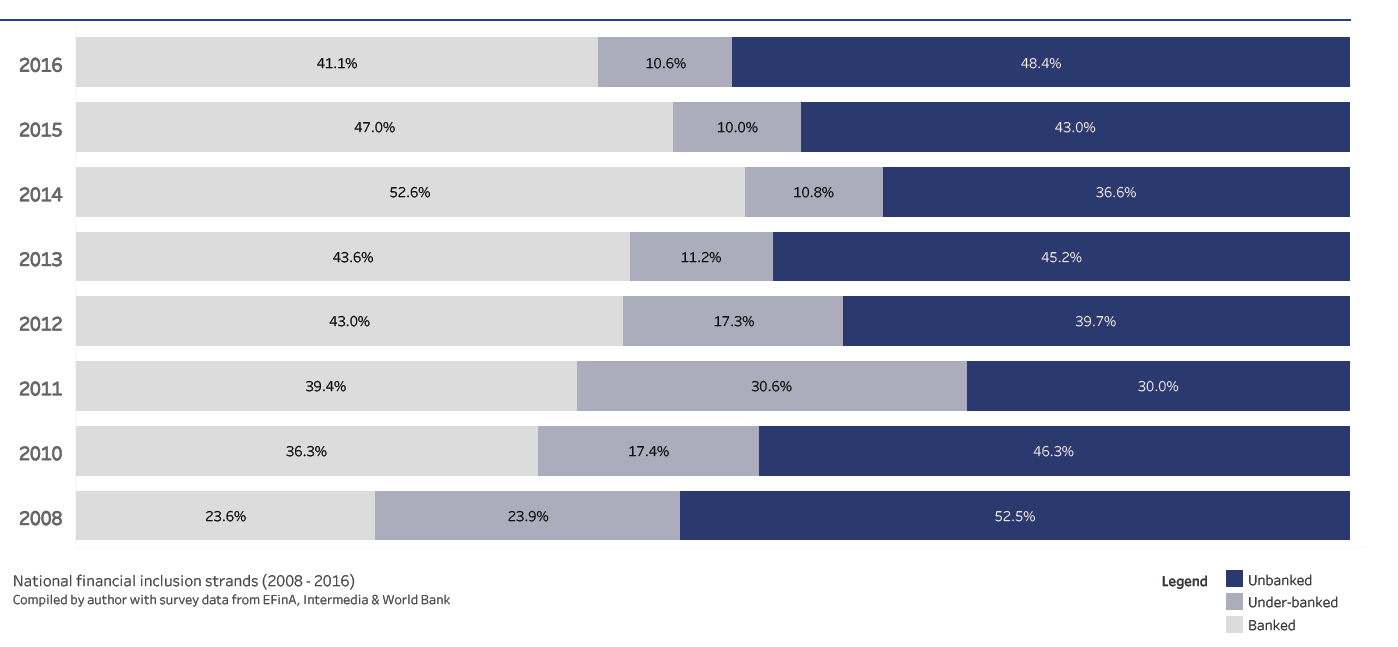

Financial inclusion — the access to and use of financial services — in Nigeria hovered around 41.1% as at 2016 (based on aggregate data from EfinA, Intermedia and the World Bank). The percentage of people using informal financial service providers like Esusu, Alajo, and thrift collectors stood at 10.6% while 48.6% of Nigerian adults use no financial service at all. That’s almost half of the country’s adult population living without financial services.

In 2012, the Central Bank of Nigeria launched a National Financial Inclusion Strategy to reduce exclusion 20% by 2020. That deadline is less than 3 years away and the gap is widening.

Due to the impending deadline, industry watchers and experts have posited several solutions, one of which involves the licensing of mobile operators (henceforth telcos) to lead mobile money operations (as done in other markets).

As stated in this earlier article, telcos in their capacity as infrastructure providers already participate in the mobile money ecosystem, albeit their independent participation as mobile money operators is forbidden. This arrangement, despite its usefulness, has several setbacks, one of which is that a telco-bank partnership means the division of interchange (transaction) fees by the partners, thereby reducing income opportunities (and implicitly profitability) even further. If telcos go it alone, profit opportunities are likely to be higher, hence their desire to obtain licenses.

However, the problem most people fail to see is that telco participation is not a magic bullet for financial inclusion. The integration of mobile operators as mobile money providers, allowing them to own and lead mobile money service delivery could solve one among a myriad of problems and inhibitors facing the digital financial services ecosystem. There are several other challenges facing the sector — low awareness of mobile money, lack of economic activity among the unbanked, relatively high cost of transactions, distance to financial service points. The list goes on (the 2016 Nigerian State of Market Report contains an exhaustive list of inhibitors highlighted by industry stakeholders).

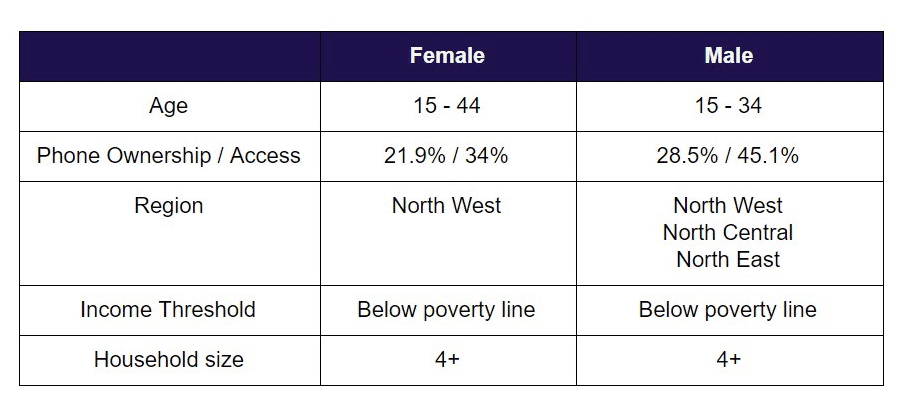

In 2017, our research covered the financially excluded Nigerian population, drawing up demographic profiles as well as their digital capabilities. We discovered that majority of the excluded are youths and women between the age of 15 – 35 and living mostly in the Northern areas of Nigeria.

Secondly, the success of mobile money is largely determined by the quality of its complementary agent network. That is, mobile money delivery at the last mile, especially in rural and remote areas, cannot succeed without the proper financial and technical investment in the network.

However, Nigeria’s agent network is pretty underdeveloped. In fact, according to the Central Bank, Nigeria’s agent network is less than 11,000 strong. That’s a big deal.

In December 2017, at the International Financial Inclusion Conference hosted by Lagos Business School, the number of agents required to effectively serve Nigeria was estimated to be at least 180,000. On the 27th of March, 2017, the Shared Agent Network Expansion Facilities (SANEF), an initiative to roll out a 500,000-strong shared agent network over the next few years, was unveiled. The plan is to have banks, MMOs and Super Agents chip in to establish the network.

Rolling out new agents, training and managing them is expensive, not to mention the liquidity requirements if the agent is to remain in business. Also, the agent business is a low profit business, meaning agents must have other sources of income.

In the midst of all this talk of extending financial services to the excluded, regulators are also very concerned about security and stability of the ecosystem itself. Which is why the BVN was introduced some years ago.

The BVN helped to streamline account ownership, allowing regulators to determine the exact number of individual account holders. This is vital information. Compare this to what obtains in the telco industry where we have a hard time determining the accurate level of mobile phone penetration. The NCC reports 146 million subscribers but we have many subscribers with 2-3 lines.

Unfortunately, the necessity of having a BVN exacerbated the financial inclusion problem due to the inability of some citizens to satisfy KYC requirements. Believe it or not, some people are identity poor. CBN developed a workaround last year in September, when they removed BVN from the list of requirements for tier-1 mobile money wallets.

Another interesting question posed in the previous Techpoint article was “can mobile operators just automatically sign up all subscribers to the service without any restriction from CBN or NCC?”

Even if telcos got the mobile money licenses and managed to sign up every subscriber on their network, it still doesn’t translate to true financial inclusion. After all has been said and done, we still have to present digital money as a better alternative to cash. People will not automatically move to digital money once it’s available. They have to be incentivised.

For example, India had to execute a demonetisation exercise in 2016 where the use of high currency notes (500-rupee notes and 1,000-rupee notes) were banned. The infamous decision which wiped out four-fifths of India’s paper currency, though bodacious, triggered an uptake in the number of mobile money users in the following months.

The bottom line is, financial inclusion is a monster facing us a country and requires all hands on deck. Telcos, independents and banks all need to participate if we’re going to successfully reduce exclusion and bring financial services to the poor and unbanked which they need to improve their lives.

You can download the 2017 DFS State of Market Report here.

About the Authors

Olayinka David-West and Ibukun Taiwo are members of the Sustainable and Inclusive Digital Financial Services initiative of the Lagos Business School. Through rigorous research, the initiative’s goal is to build an evidence base and sustainable business models for digital financial services to reach the unbanked and underserved.