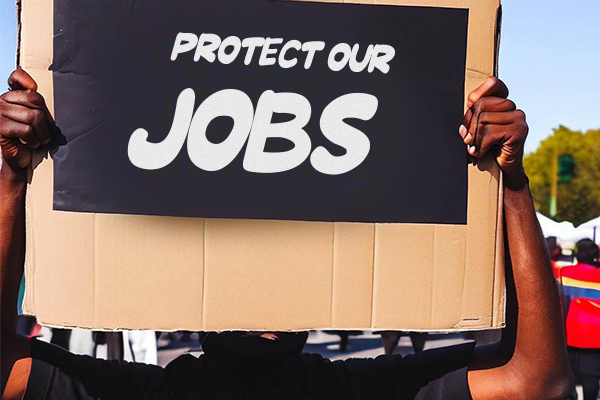

In July 2024, Kenyan ride-hailing drivers found themselves in a familiar, yet frustrating, situation. After taking a brief break from demanding fairer working conditions from platforms like Uber and Bolt, they embarked on a five-day strike and took to the streets to protest.

They typically demand better rates, safer working conditions, and more transparent communication, but it seems with every try, they continue to feel undervalued by these platforms.

Even when the platforms sometimes respond, the changes barely scratch the surface of the drivers’ concerns.

A few days ago, ride-hailing drivers in the country intensified their efforts, defying platforms’ policies and even risking suspension, by setting their own fares.

The drivers had no other options, and while their actions did not change the situation, considering how users responded to the hiked fares, the move got Uber’s attention.

Uber responded with a price review that barely addressed their issues. The tech company stated they could only offer so much due to profit margins and market competition. However, drivers argue that they are struggling under the weight of rising operational costs.

Given how long this seemingly unending tussle has been going on, the drivers might not win without external interventions.

What is going on in Kenya is not new, as other markets in Africa have similar stories to tell. In 2022, ride-hailing drivers in South Africa went offline for three days to protest against unfavourable working conditions.

Ride-hailing drivers in Nigeria protested nationwide in 2023 as they requested a 200% increase in fares. South Africa’s demands were directed at the government and regulators, but drivers in Nigeria tried to force the hands of the platforms, just like the drivers are attempting in Kenya.

These approaches call into question whether the incessant demands are reasonable and if they are being directed to the right quarters.

Blurred lines in the African gig economy’s legal framework

Africa’s gig economy has seen significant growth over the years, with major players like Uber and Bolt in the ride-hailing sector.

This booming industry has provided flexible work opportunities for millions but is not without its challenges. Ride-hailing drivers often find themselves trapped between the promises of platform independence and the harsh realities of providing their services.

This could be because the law is not clear on their rights, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation, and with little consolation when platforms change terms or conditions without consulting other stakeholders.

Damilola Mumuni, employment lawyer and Team Lead at The Dream Practice, explains how labour laws globally were not written with ride-hailing in mind.

“Some work categories have come up as technology and development continue to shape our workspace and economy. By the nature of their tasks and roles, gig workers are categorised as Independent Contractors.”

This is the case in most countries, including Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. This classification goes on to indicate what type of employment contract they get and the kind of protection they can afford compared to a clear employer-employee relationship.

“The contract or arrangement in place is what would define the type of employment or classification. This means there is a possibility that gig workers may qualify as employees of the companies they work for.”

While there’s only a little chance that these workers can be considered employees, this is one thing these tech platforms have refused to admit across their markets globally.

In 2020, a judge in California ruled that ride-hailing drivers are employees and not freelancers; the ruling was appealed and overturned in 2021, only to be upheld by three appeals court judges in 2023.

In July 2024, the Supreme Court further established that these platforms could keep operating as they were with drivers considered as independent contractors.

Unfortunately, there’s only so much gig economy associations can achieve without the platforms accepting them as employees.

The current legal framework often fails to differentiate between gig workers and traditional employees, and this shortcoming has led to a significant gap in protections.

This legal grey area allows platforms to sidestep responsibilities that would typically fall on employers, such as ensuring fair wages, providing benefits, and guaranteeing job security, all of which drivers are demanding.

Many African countries treat gig workers as independent contractors, thus stripping them of basic labour rights and benefits.

How does the law differentiate these classifications?

“The criteria used to differentiate between Independent Contractors and an employee have to be the level of control, the remuneration style, the work model, or style of reporting.”

Defining the level of control and style of reporting, Mumuni points out how this group of workers have a more flexible situation, defining where and how they work, reporting at their own pace, and requesting to be paid in a manner different from employees. But this comes at a cost.

“Independent Contractors might miss out on benefits like HMO, pension, and other statutory advantages, as they are viewed as external service providers rather than full employees.”

It won’t be out of place to wonder if these workers are truly independent, or have been misclassified to the detriment of their rights and well-being.

Gig workers, like all other workers, have the right to be paid for their work, can have their employment contracts or arrangements terminated, and have to remit income taxes. The platform has a responsibility to act honestly and fairly towards them, while workers are not expected to aid competition to the detriment of the employer, among other expectations.

Mumuni explains this further.

“Terms and conditions that should regulate their relationship should be an agreement or arrangement on the scope of work, duty, and tasks. It should also detail work hours, insurance, third-party liability and the scope of such liability. Remittance of statutory payments, fees, taxes, compensation, provision, use and maintenance of vehicles, machinery, or tools required to work should be clearly stated.”

Are gig workers’ demands misdirected?

Mumuni explains that the law permits gig workers to negotiate their fees or payments, but “the ability to do this is largely impacted by the state of our economy in line with the law of demand and supply. The specific needs of the industry involved are also important.”

The peculiar situation involved would determine the position of the gig workers and their bargaining power. If it is a highly technical or specialised workspace, the workers might have much bargaining power.

Unfortunately, the ride-hailing space is not considered highly specialised.

Income insecurity is the expected outcome from the provisions of being an independent contractor as workers’ bargaining power has already been compromised. Consequently, these workers’ incessant requests might continue to go unattended or receive little attention.

Mumuni recommends that gig workers document their challenges and have other stakeholders review them to spot where pain points can be addressed.

Stakeholders like government agencies and regulatory bodies can push for policy changes or legal interventions to change the situation; however, they haven’t had any noticeable impact in the affected countries.

If the relevant associations and users get more involved, governments might assume a role that ensures fair competition among these platforms, including fare determination.

“Whichever route would be taken, the challenges must be identified as well as the solutions to cure these challenges in line with our prevailing peculiarities and economic situation,” Mumuni concludes.