Key takeaways

- Urban Migration in Africa is increasing, and while that is not bad, the infrastructure in African cities cannot keep pace. As a result, more Africans are trading rural areas’ lush nature for urban slums.

- The Internet is fast becoming an essential infrastructure on par with electricity and healthcare. Today, research has shown that companies go where the Internet goes, and it has the potential to reduce unemployment.

- Starlink plans to launch in Nigeria by Q4 2022. Iit holds massive potential for connectivity in unserved areas and could provide healthy competition for Nigerian telcos. But some concerns need to be addressed before this could become a reality.

In 2012, my dad handed over his old Nokia 6070 to me, and I believe that was a life-changing moment. Built like a tank, with goosebump-inducing ringtones, the phone’s GPRS connection opened up a world of possibilities for me while living in one of Nigeria’s rural communities.

Having exhausted all the physical novels I could find, I spent hours on Gutenberg.net, perched beside a window in the house, or a tree in the compound, looking for the spot with the best reception. Let’s not mention games and songs from Sefan.ru or Waptrick.com. I’m trying to come off as a serious teen here.

I wish I could say this was the experience for the average teenager living in a rural Nigerian community. I’d dare say I was lucky to own a feature phone that could access the Internet. Over 10 years later, and using a home fibre connection in Lagos, I can’t help but notice I missed a lot.

You can imagine my excitement when I saw Elon Musk’s Tweet on May 27, 2022, that Starlink was set to begin operations in Nigeria by Q4 2022. Starlink, a subsidiary of space exploration company, SpaceX, uses satellite technology to beam Internet signals down to earth.

You might be asking, what’s the relationship between satellite Internet and my experience in a rural area years ago? Well, why don’t you read on and see.

Migration trails opportunity

Between 2012 and 2021, reports show that millions of Nigerians joined me, leaving rural communities searching for better pastures in big cities. Statista states that almost 53% of Nigeria’s population lives in urban areas, compared to 45% in 2012.

Fun fact: In 2007, the percentage of people living in cities outgrew those in rural areas for the first time in human history. At that time, Africa and Asia were the only continents where rural outnumbered urban.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicted that Africa’s population would double between 2015 and 2050. That’s an extra 1 billion people; per the OECD, 750 million will live in urban areas.

A closer look will reveal that these people are looking for jobs, better healthcare, and quality education. As long as the most prominent companies set up shop in big cities and high-quality hospitals and schools move with them, enterprising youths will quickly follow.

This would not be a problem in a sane world, but in sub-Saharan Africa, migration is moving faster than its infrastructure can handle. Hence, we have 60% of urban dwellers living in slums.

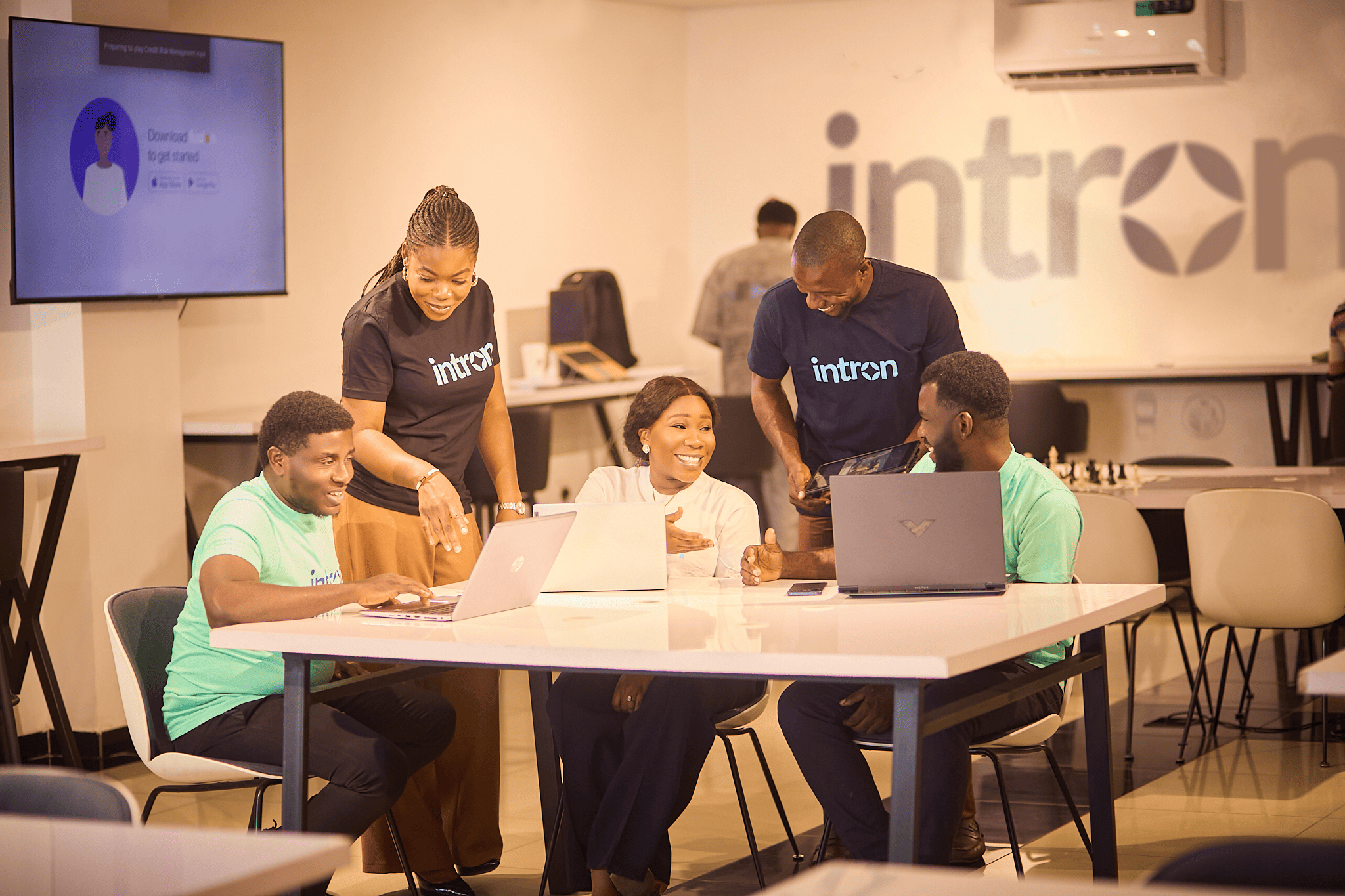

You must have heard that the pandemic would bring a drastic change with the rise of remote work. Remote work allowed companies like Ulesson, and TalentQL to leave the urban giants of Abuja and Lagos to less developed cities like Jos and Ile-Ife in 2020.

For various reasons, both companies have moved back to Abuja and Lagos. If you want to replicate that move, you’d have to deal with the infrastructure divide between the cities in question and the ensuing issues.

Since the dawn of the millennium, more and more businesses base their entire business model on the Internet, determining where they set up shop. A study from the University of Maryland in the US even shows that fast and cheap Internet would reduce unemployment rates.

Hence, you can safely add Internet access to essentials like electricity and quality health, which are urban areas’ distinctive features. However, few Nigerian cities can boast of quality Internet catering to large companies or heavy Internet users.

Even though some less urban Nigerian states have tried to incentivise telcos to build infrastructure in these areas and decongest Lagos, my discussions with them point out one big question: Does it make business sense?

The question makes sense

In 2020, the Ekiti state government in Nigeria announced plans to create a hub that would power a tech ecosystem away from Lagos. It slashed right of way charges, fees usually levied on telcos to lay fibre infrastructure and laid a blueprint for what it called a knowledge zone.

MTN reportedly got government approval to build 160km of fibre optic cable around the city. Despite these developments, there were still some concerns. To understand them, you’d have to read this article that shows how the Internet works in Africa.

If you stubbornly refused to click on that article, let me sum things up as quickly as possible. The Internet is powered by a massive web of fibre cables laid at the bottom of the ocean and connected to all the world’s major continents.

It wasn’t until Cleo Abram, a former Journalist at Vox, pointed out that I realised that the language we use for the Internet does not really sell how it works. Hearing words like download, upload, and cloud, you’d think the Internet is in the sky rather than a bunch of computers connected with a gigantic web of cables.

The fibre optic cable travels at light speed, so computers can communicate faster than any other medium. The problem is these fibre optic cables are expensive and cost anywhere between $3000 – $50,000 to lay 1km of them. The MainOne cable is 14,000km long, so do the math.

In cities, 1km of fibre optic cables can serve several buildings at once and provide quick investment returns, but in sparsely populated areas, that same 1km will reach much fewer buildings. The more high-quality houses are close together, the better for telecom companies.

Without businesses and entrepreneurs, most infrastructure providers would be reluctant to move outside the juicy parts of Lagos, Abuja, and others. Without these infrastructures, businesses and entrepreneurs will not, well, you get my point.

So what can help break this cycle?

That’s where Starlink’s Satellite Internet comes in

Once a telco deploys fibre in, say, Nigeria, it would need fresh capital to deploy in Ghana. Ideally, a company with enough orbiting satellites can serve Nigeria and Ghana without expending more cash. I say “ideally” because things are rarely ever straightforward.

Satellites use radio waves to communicate with the earth. Standard satellites should be 36,000km above the planet, but signals are slow to reach the Earth. That’s why satellite Internet service providers like Starlink orbit as low as 500km.

Beyond sending signals down to earth with radio waves, the company’s satellites also communicate with themselves through, you guessed it, light. Light moves faster in space than in water, making it a healthy competition to fibre.

According to this article, each Starlink Satellite could cost $250,000 each.

Fun fact: Starlink has launched 2300 satellites currently orbiting the earth, and is now able to serve 32 countries globally. The only significant reason it would need to set foot in these countries is to acquire a license or set up customer support centres.

GSMA reports that more than half of the population in sub-Saharan Africa, still do not access the Internet. There are several systemic issues which I won’t go into yet. In summary, Africa has tons of problems to grapple with.

If Starlink launches, the company has the luxury of waiting for the millions of Africans still without a smartphone to come online. In the meantime, its satellites can keep serving other countries.

Concerns and benefits

The benefits

Reports show that Starlink could get speeds comparable to fibre optic connections in the US and Canada. Imagine the possibilities of running a high-value palm oil processing plant in any of the remote areas in Nigeria with a Starlink connection.

While I’m not suggesting that people will leave cities like Lagos, Accra, or Nairobi, we can take a leaf from the ASEAN region in Asia, which has countries like Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore develop their economies based on their respective strengths.

If such capabilities arise in African cities, the need to migrate to more urban areas will lessen.

Another key part of the fast Internet I haven’t mentioned is data centres. To oversimplify things – the data centre brings that connection closer to you instead of transmitting data from Nigeria to Portugal through the fibre cable. As a result of data centres in Africa, streaming services have gotten much better, especially in major cities.

So far, most of Africa’s data centres have been located in Lagos, Accra, Nairobi, and Johannesburg. With satellite Internet, companies can install modular data centres in remote locations. In 2020, Microsoft unveiled one of such centres, which gets Internet from Starlink.

This will prove especially useful for organisations involved in humanitarian action, mineral exploration, or military expeditions that would need cloud facilities.

Add in the fact that you could also use Starlink in vehicles (Recreational Vehicles); it’s not hard to see the appeal.

Beyond all these, the benefits can snowball into something that could reduce the temptation to migrate for millions of teens in rural areas, who, like me in 2012, cannot access the quality Internet, education, and job opportunities found in big cities.

Local competition

While Starlink could threaten telcos, it could provide healthy competition. If Starlink eventually incentivises companies to leave congested African cities and set up shops in relatively remote areas, it creates avenues for other Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to follow suit.

Rather than have people concentrated in one or two economic hotspots, they would be spread out based on interests and economic opportunities. The data shows that better Internet should provide quality healthcare and education in more parts of the continent.

However, we need to point out the concerns.

The concerns

Starlink requires thousands of satellites to be close to the earth and could be a challenge to the environment. Trees could block their signals, and bad weather conditions could reduce the speeds of cause outages.

Trees and severe thunderstorms are prominent features in Africa. Anyone who uses Multichoice’s DStv or other cable services should have observed the drop in quality when there’s rainfall.

Another central argument against Starlink is its price. At $110 (~₦70,000) for preorder and $599 (₦390,000) for a complete kit that includes the terminal, mounting tripod, and Wi-Fi router, most Nigerians and Mozambicans might not be able to afford it.

Its premium service costs $2,500 (₦1.7 million) and $500 (₦350,000) monthly subscription.

We found some hopes on its website, though, as it appears Nigerians can pre-order Starlink for $99(₦68,000). It’s, however, not clear if that’s the only cost involved. We’ve reached out to SpaceX for comments on these talking points but are yet to get a response as of press time.

In the meantime, let us know what you think about Starlink. Whew, this was a long one; I hope you found it helpful.