For those who discovered crypto early, between 2009 and 2019, getting scammed seemed like a right of passage into the space. Back then, very little information was available on navigating the crypto space; unsurprisingly, we saw some of the biggest crypto scams.

While the crypto space is still nascent, there have been significant changes since the creation of Bitcoin. Several exchanges, such as Binance and Quidax, have somewhat simplified accessing, trading, and using cryptocurrencies.

However, even with the availability of information, scammers have advanced, and crypto scams are almost a regular occurrence.

According to Chainalysis, crypto scams increased by 900% — $1.4 billion to $14 billion — between 2017 and 2021. It is important to note that this does not mean bigger scams are happening, and it means more people use cryptocurrencies; therefore, crypto scammers have more targets.

On today’s edition of the Emerging Tech Africa series, Adedeji Owonibi, cryptocurrency forensics expert and Founder of the blockchain company, Convexity, talked about the science behind crypto scams and how easy it will soon be to find scammers.

Some of the biggest crypto scams in history

The OneCoin scam

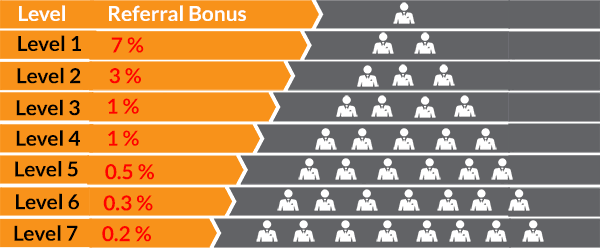

The OneCoin scam is perhaps the biggest and most creative crypto scam ever recorded. This is because while other scams involved the scammers doing technical work like creating ICOs and launching tokens, OnceCoin promised investors something that never existed digitally or physically.

In 2016, the mastermind behind the scam, International Law PhD graduate, Ruga Ignatova, appeared in front of 90,000 people in Wembley Stadium, London, to sell the deceptive OneCoin dream.

The OneCoin scam was massive not only because Ignatova carted away $4 billion but because she got unsuspecting multitudes to rally genuinely behind a Ponzi scheme.

Even after allegations surfaced that the entire thing could be a sham, the unwitting victims, more accurately, fans, defended the scheme.

After OneCoin’s launch in 2014, the scam continued until 2017, when German authorities issued cease-and-desist orders against it.

In OneCoin’s case, investors were not buying tokens; they were sold plagiarised crypto educational materials costing between €100 ($101) and €225k ($228k).

The scam almost doesn’t deserve to be called a crypto scam, but the promise of a coin as valuable and even better than Bitcoin makes it qualify as a crypto scam. Crypto and blockchain were merely a smokescreen to hide the scam’s true nature.

By 2019, all critical players behind the scam were arrested, except Ignatova, who remains at large.

BitConnect scam

This scam, which happened in 2016 during the initial coin offering (ICO) boom, saw investors kiss $2.4 billion goodbye.

An ICO is a way for crypto projects to raise money; it is the crypto industry’s equivalent of an initial public offering (IPO), but without the regulation. With ICOs, anyone can present a project proposal and get millions of dollars in funding without any regulatory consequence.

To raise funds, the project or company launches a token, which interested investors purchase. The tokens are like company stocks or equity, which can sometimes represent project ownership.

Founded by Indians, Satish Khumbani and Divyesh Darji, the BitConnect ICO was very convincing and promised investors a 40% guaranteed return on investment (ROI); investors willing to take more considerable risks could earn a lot more.

In the volatile world of crypto, nothing is guaranteed. Still, BitConnect assured investors that it had a proprietary “trading bot and volatility software” that would trade Bitcoin and make them a fortune.

For context, the promised ROI meant a $1,000 investment could become $50 million in three years. These numbers appealed to investors who continued to buy BCC, the project’s native coin.

However, these returns were unsustainable, and by 2018, BitConnect suddenly shut down. The US and UK governments got wind of the shady business and started investigating the company. Initially valued at over $400, the BCC coin plummeted to $1 in less than a month.

Mirror Trading International

Mirror Trading International (MTI), run by Cornelius Steynberg, a South African, was charged with $1.7 billion fraud by the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) on June 30, 2022.

MTI’s scam was similar to BitConnect, as investors were lured into investing in a commodity pool that could make them 0.5% daily ROI, with Steynberg claiming that trading would be done by error-free artificial intelligence (AI).

The fraud scheme, which started in 2018, caught the attention of regulators in 2020. At that point, Steynberg had already gathered over 20,000 bitcoins valued at over $1.7 billion.

South Africa’s Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) launched an investigation into MTI and revealed the company was operating without a licence.

Authorities are currently helping liquidators recover investor funds and hopefully refund victims of the billion-dollar fraud.

It is easy to track criminals down on the blockchain

Adedeji Owonibi is a Cryptocurrency Forensic Investigator, and he believes that tracking down criminal activities of scammers on the blockchain is easy, but the hard part is putting a face or name to who is perpetrating the act.

For context, a quick visit to the blockchain explorer — a website that shows transactions on the blockchain — will give you real-time updates on all the transactions happening on the Bitcoin blockchain. You can even enter an address you’ve sent bitcoin to and find out what the person is doing with it.

However, if you follow the money long enough, you might be able to track down scammers. Turning cryptocurrency to legal tenders such as the dollar, rand, or naira could require sending the crypto to centralised exchanges with know-your-customer (KYC) protocols.

While the blockchain keeps track of everything, Owonibi said there are tools that criminals use to throw government agencies off track called crypto mixers.

Crypto mixers, also known as tumblers, are used to jumble up transactions and make it hard to figure out who sent what.

Think of them like a cement mixer. Once the dirty bitcoin has been poured in, it is mixed with another large pile of bitcoins, and then clean bitcoins are delivered in smaller bits to a chosen address. Looking at it through a regular banking lens, ₦20,000 ($47) put into a mixer will be mixed with billions of other transactions bouncing off different parts of the world and paid into a specified account in little amounts until they reach ₦20,000.

According to Owonibi, Wasabi is one of the most popular mixers used by scammers. Other mixers include Blender, Anonymix, and Bitcoin Laundry.

“Wasabi is a way to obfuscate trades and make it difficult for investigators like us to track.”

Owonibi said that in the MTI scam, 29,000 bitcoins were sent into the popular Wasabi mixer. These mixers have made getting away with crypto scams easier; however, he guaranteed that there are sophisticated tools that can still make these transactions traceable.

Interestingly, he revealed that the anonymity in the blockchain space would not be that way forever, as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) — an intergovernmental organisation founded to combat money laundering — is working to put a face to transactions on the blockchain.

“It is called the travel rule protocol or travel rule standard. We’ve (Owonibi and the FATF) been working on it since 2019 and have developed a standard called IVMS 101, and over 130 of us globally worked together to bring out that standard.”

While this is still a work in progress, Owonibi says the standard could bring something similar to bank KYC to the blockchain.

Decentralisation, the primary tenant of cryptocurrencies, makes it almost impossible to eliminate the concept of anonymity, but if Owonibi and the FATF can make the travel rule protocol a reality, it will be a watershed moment for the blockchain industry.