One of my favourite lines from Jidenna’s 85 to Africa project is from the song Worth the Weight. The song features Seun Kuti, and the following monologue from the artiste probably captures some of what community-driven platform, Bantaba is doing.

“I believe it is time for an African people-powered highway. A highway that will connect the diaspora and the motherland. A global highway for African people all over the world to rediscover themselves and remember that the only thing that unites black people globally, the only thing we have in common, is that we are from Africa.”

When most of us hear the word diaspora, what comes to mind is in-laws or relatives abroad. For some, this could mean gifts like clothes, toys, jewellery, or money (the holy grail), which we sometimes like to call remittances.

Last year, people in the diaspora sent back $45 billion to family members and friends, and this amount depicts how much money comes into the African continent annually. Interestingly, despite World Bank predictions stating a possible 20% decline for low and middle-income countries due to the pandemic, that year, remittances declined by only 1.6%.

In some countries like The Gambia, Lesotho, and Cape Verde, these remittances contribute considerably to their GDP.

But let’s circle back to how these remittances come about. Many diasporans leave their country in search of better jobs and opportunities. Although some go to get an education, we could estimate that the raison d’être is almost always the former.

In the long run, this means that depending on the type of job and the length of stay, these diasporans attain some level of experience. Some of them work with big tech companies like Facebook, Apple, Google, and Microsoft, and some work with investment banks or companies.

Essentially, there is a well of largely untapped diasporan knowledge.

At Bantaba, Lamin K. Darboe and his team of diasporans (and non-diasporans) are looking for ways to ensure this wealth of knowledge and cash trickles down to African tech startups that need them.

One of such diasporans is Pierre Jallow, a Gambian and the Founder and CEO of Webridge, a company that connects Nordic/Baltic businesses to the African market and vice versa. He is also the Co-founder of Remode, an entry-level accelerator.

But before his life in tech, Jallow was a professional basketball player. He moved around quite a bit and played in Finland (his current homeland) before moving to Russia and then back to Finland.

The way Jallow sees it, Bantaba is helping to expand the Ubuntu philosophy of “I am because we are”, which, for most people, has come to mean doing right by their family, tribe or community.

“All of a sudden, you don’t have to say, ‘Okay, my remittances are only going to my parents or people in my family’, or ‘I’m just going to keep my investments in Europe where it’s not going to develop locally.’But you are saying with my $10, $20k, I’m going to invest in a due-diligence ready company, in a vetted company. That is the platform that Bantaba gives these investors.”

The journey to Bantaba

When Darboe left the shores of Gambia for India in 2012, it wasn’t because he had dreams of founding a startup. Far from that, in fact. Like most young people — sometimes a little older — leaving Africa, Darboe left to get an education.

But his journey to India would lead him to Italy.

“During the same year, I had another scholarship offer from a University in Milan, Italy, and that’s how I moved to Italy, where I completed my undergraduate [studies] in finance. And then, like many finance graduates, the choice was maybe investment banking or consulting. So I tried to follow one of those routes.”

That would take him to Ireland and then back to Italy, a decision that would introduce him to the startup world.

“At the same time, I was working with a partner who was an angel investor and had investments in many tech startups in Northern Italy.”

In August 2019, Darboe moved to Stockholm for an MSc at the Stockholm School of Economics.

In June 2020, he met three other African students — Fabrice Ouedraogo, Eliane Birba, and Noufou Kafando — in a climate action challenge organised by Norrsken Foundation and Stockholm Innovation & Growth (Sting).

Although they would eventually crash out, the stage had been set for future collaborations, and the current result is Bantaba.

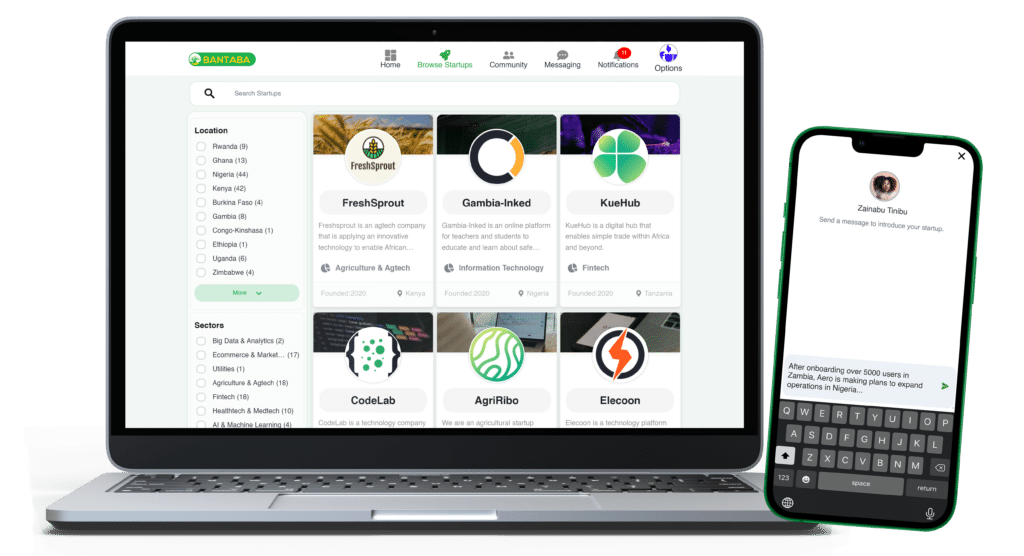

The way Darboe explains it, Bantaba match makes diasporans with tech experience and who want to give back to the African continent through startups looking to raise capital, cultivate mentorship relationships, or receive consulting services.

A way to think of this is by using the meaning of Bantaba. It’s an ancient Manding word used to describe a large tree in the village square under which elders came to discuss things that affected everyone in the village.

Likening this to the digital platform, Darboe describes Bantaba as a square-like convergence of the diaspora and tech startups to “address the challenges back home.”

What Bantaba is not

While we’ve established what Bantaba is, what should you not mistake Bantaba for?

First off, while it has similarities to (in)famous matchmaking platform, Tinder, in terms of matching tech startups in need of professional advice and funding with diasporans who can provide those things, finding love is not the goal. Darboe finds the idea “sexy,” but unfortunately, not entirely representative of all Bantaba does.

Side note: If you find love while using Bantaba, please reach out; I love to hear such stories.

It is also not LinkedIn. Although it creates a community of professionals, it is more focused on the diaspora and tech startups, a positive which Darboe believes can open room for monetisation in the future.

Another thought to scratch off the list is an accelerator or an incubator. Bantaba is none of those things, and while it does allow startups to create the kind of relationships you’d get with those, it has a different approach.

Also, it is not strictly a platform to raise money. While that option exists, it is not the primary offering. Like the typical funding round, money is exchanged for equity. However, like GetEquity, a cap is placed on how much is raised. There is, however, no official market for secondaries.

However, like with most community-centred apps, each user has a profile. But, before it is created, the startups and diasporans go through a vetting process to ensure that all is well. All the data provided is used to match startups and diasporans with similar needs.

Bantaba also provides Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Miro credits to startups on the platform based on the partnerships it has with these companies.

In the end, the idea was birthed out of Darboe and his co-founders’ interests in engaging with the African continent, bridging the gap between the diaspora and the tech community, while building a community of experts and potential investors.

Currently, Bantaba takes a 5% fee off any successful funding deal they are directly involved in. This means that if a startup joined the platform to raise money and Bantaba matched them with an investor who proceeds to give them money, Bantaba makes money off this.

While I wonder how sustainable this would be in the long run, Tomiwa Onaleye, Bantaba’s Content Strategist, tells me the end goal is to earn enough money to “keep the company’s lights on.”

This is doubly tricky when you realise that a startup can make these connections on its own on the platform and possibly get funding without Bantaba knowing. But Onaleye says they are not necessarily bothered about that.

So far, Bantaba has raised $425,000 in pre-seed funding from Swedish angel investors. For subsequent rounds and keeping with their current business model, Onaleye says the company is in no rush to bring just any kind of investor on board.

But are there plans to open up the platform to non-diasporans?

Although Darboe doesn’t rule out this possibility, he makes a statement reminiscent of our introductory anecdote: “I believe it is time for an African people-powered highway.”

“I think it is a good way for Africans to be part of their own development before you bring in other people.”

And Jallow agrees.

“No country was developed by others. Every country in this world was developed by its own people. Whether you consider one of the countries in Europe or North America, they were developed by their own people.

“And the same goes for the African continent and the countries within the continent, and if its own people don’t get up, we don’t develop it. And I think this is the chance Bantaba creates.”