When you think of farming, the image of a farmer in a remote village, working everyday under the sun, with basic farming tools comes to mind. Such image hardly inspires confidence in farming. Well, all of that is beginning to change.

I journeyed to Ijebu-Ode, a small commercial town South-West of Nigeria, one wet afternoon. There, I met a young man named Femi. He took me to his farm, it was a sea of green vegetation which flowed spectacularly towards the horizon.

“This (pointing to a particular portion of it) is a 10-hectare farmland belonging to one Mr Daniel who is based in the UK”, Femi tells me, “He is a chartered accountant and one of my biggest clients.”

Femi is into the business of managing farmlands for his numerous clients; from acquiring the lands to planting, harvesting and then sales. “I have been in this business for over 2 years. I also grew up in a family that cherishes farming a lot,” he remarks.

Majority of Femi’s clients are white collar workers. Their knowledge of farming is between little and average, so they rely on the experience of Femi and a WhatsApp group he created to receive updates about their farmlands.

WhatsApp groups no doubt are increasing in popularity, as people use them for different purposes. For Femi, this is the perfect avenue to keep in regular touch with his clients. However, using WhatsApp to manage an agro project has its challenges.

Ade, one of Femi’s clients, laments about the pain of waiting days on Femi to upload pictures of farm progress on the group. “Sometimes he simply doesn’t give us any and that is our major grouse with him,” he tells me.

“Farming itself is big work; professional farm management is harder,” Ade admits. I couldn’t agree more with him.

Combining the work of managing the farms with being the group’s admin can be tedious work. For just one person, it is inefficient. There’s an easier way to go about these tasks. The technology that makes it possible does more than just sharing real-time updates to allay farm owners’ worry.

Technology as an enabler

Beyond the many ways in which technology is advancing farming operations, it has simply also turned farming itself into a real business. Few days before Ijebu-Ode, I met and discussed with Onyeka Akumah, CEO of Farmcrowdy, a digital agriculture platform, to get insight into how technology is driving the business.

“It’s amazing what we can do with technology. With our model which enables us to use technology to crowdfund investment for farmers, we are able to increase both output and revenue at the same time.”

According to Onyeka, one vital aspect of decision making when it comes to owning or sponsoring farms is the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) facet. Any system providing for such must be designed in a way that allows potential sponsors easily decide whether they want to commit investment in farms. More importantly, it must be free of all bottlenecks that impede trust in the system.

“Right from their mobile phones and laptops, they should be able to get help without consulting anybody,” Onyeka says.

One investor who has experienced first-hand how seamless this technology can be is Subomi Plumptre, a social media personnel. Rather than patronise one-man operations like Femi’s, she opts for a more organised platform. She narrates her experience on her personal blog.

“My first investment was a sponsorship of investment on 5 farms. The tenure was a few months. The subscription process was easy and I had the option of registering with my email address or logging in via Facebook. I filled all the information on the website and paid via WebPay at 8 pm. As a social media professional, I loved the fact that I could conduct the entire process remotely, without talking to anyone on the phone. I received fortnightly updates on the farms with pictures and was given the option of visiting the farms in person to verify progress. After the investment period, I received my principal and profit (of about 20%) as a credit to my bank account.”

With advanced technology making it possible to carry out (virtual) farm management with ease, I wonder why Femi is still stuck with a WhatsApp group.

He assures me he is working on “something” that will automate many of his processes and bring in more reward to his investors.

The scope of investment farming in Nigeria

Comparing modern farming with traditional farming methods, one can see numerous advantages — not getting one’s hands dirty, the allure of extra cash, to mention a few.

If Mr Daniel living in the UK could operate farmlands in Nigeria, one wonders if Nigerians resident in the country are keying into this opportunity.

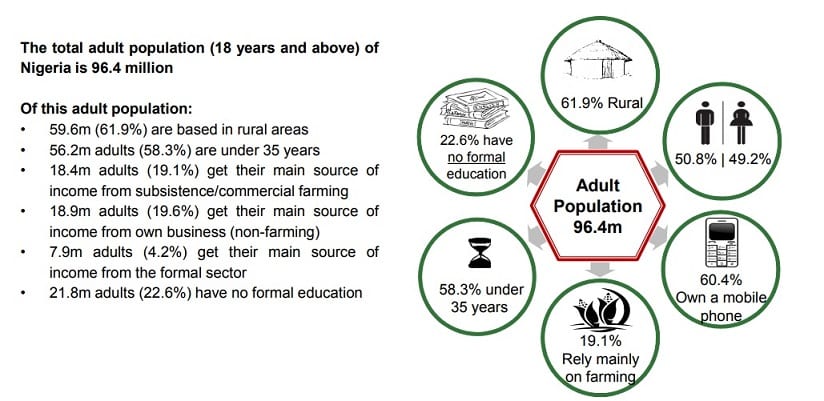

According to the Efina demographic profile of the Nigerian population, the total adult (18 years and above) population is 96.4 million, of which 59.6 million (61.9%) live in rural areas. Shockingly, only 18.4 million adults (19.1%) get their income from either subsistence or commercial farming, while a mere 7.9 million (4.2%) get their main income from the formal sector.

This begins to give us an idea of the percentage of Nigerians playing in the agro sector and investing in farms.

The UK, for instance, has a history with investment farming. In fact, the rise in the number of private investors buying UK farmlands as investment has forced cost to rise significantly.

A farmland in England now stands at around £8,000 – £12,500 per acre — a far cry from the £1000 per acre rates typically paid in the early 1990s, Financial Times reports.

I can’t help but think this is the sole reason why Mr Daniel opted for farmlands in Nigeria.

“When he first contacted me, he wanted to buy off these farmlands,” Femi recalls, “I then advised him to go for a lease instead because people do not know it’s easier that way and a lot more cost effective.“

There are at least one million hectares of government-owned farmland available for farming in remote villages across Nigeria, managed by the River Basin Development Authorities (RBA), Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs) and farm settlement schemes. These farmlands are leased at about ₦1, 000 per hectare (a hectare is equivalent to two and a half acres) for a period of about eight months.

But Femi argues that the price quoted for the land is subjective as one still has to pass through the local community elders to get proper pricing.

“It could be ₦5000 for individuals with 1 or 2 hectares and ₦10,000 for corporate or large farmers,” he adds, “These variations among others is one of the reasons why there is a general lack of knowledge on how best to secure these farmlands.”

Perhaps if the information is readily available to Nigerians, more people could come out to invest in farms and hopefully give the economy a boost in the face of diversification.

Possible ripple effects on the economy

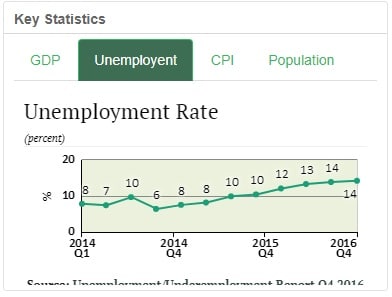

Nigeria’s unemployment rate is unbelievably alarming, rising for the ninth consecutive time since Q4 2014.

And as oil prices drop, we can turn our attention elsewhere. From the look of things, there’s enough incentive now to look into investment farming, as it holds attraction not only for farmers but also for individual investors willing to let others do the spadework.

For instance, Femi explains that a hectare of maize farm can yield 4 to 7 tons of grains. A ton, as at the time I spoke with Femi, sells for ₦140,000.

“With a principal investment of ₦150,000 — ₦200,000, you could reap about ₦500,000,” he explains, “That’s over 200% profit margin from maize only in less than six months”.

“Yet one could seize the opportunity of planting and rotating different kinds of crops on same or multiple farms” he is convinced.

I visited Abuja within the same period and found out one does not need that much to invest in farms.

There, Thrive Agric, another agro crowdfunding platform with a proprietary right to over 130 hectares of arable land in Rijana — a rural community in Kaduna — alone, receives sponsorship from investors for certain farms at a considerably less amount.

One of the co-founders, Uka Eje, tells me they market harvested produce even before it is planted.

“We get a forward contract and a lease of intent from off-takers (processing companies) who show interest in buying the commodity. From there we already know how much we are selling and how much is due to sponsors upon harvest,” he says.

Nigeria is reported to have over 82 million hectares of arable land and a climate that allows all year farming of crops like maize, cassava, cocoa, rice, sorghum, groundnuts, palm oil. Unfortunately, only about 40% has been cultivated.

If properly utilised, the ripple effects would encourage many “internet farmers” like Daniel and Subomi to come out of their shells and embrace farming; creating in the process, a steady stream of income that keeps many from falling into perpetual poverty while also catapulting others into Nigeria’s growing middle-class. Again, the good thing is one doesn’t necessarily have to be involved in the day-to-day grunt work as the case may be. From a laptop or mobile phone with a little money, anybody can access this goldmine of an opportunity.

The idea that everybody should own a farm is amazing. No doubt in the coming years, more investors will likely look into the agro sector. But while that’s a boon for the sector, Carol, a hands-on farmer based in the highbrow Ajah axis of Lagos, says that some of the investment adverts she has seen are too good to be true. She advises that potential investors do due diligence to ensure that the investment is genuine and viable.

“They also need to approach it with the mindset that anything could go wrong and they could have lower than advertised returns or lose their investment completely,” she adds.

Femi’s companion, Gbadegbo also warns that the consequences of an unguarded influx could birth a demand and supply problem. He advises potential investors to focus on growing varieties as opposed to growing a particular breed of crop.

In all, I see there’s an opportunity here for Nigerians to take advantage of. Thanks to technology, it’s not so much of hard work after all.